Dharnish Iqbal takes a look at how what teams can and cannot do in the middle of the pitch is a strong indicator of the effectiveness of an overall tactical approach and the ability to solve problems

The next time you watch a football match, pay attention to the players in the middle of the pitch and their actions. There’s normally something interesting going on.

Whether a player positioned centrally can find space, receive the ball and turn, is a good indication of how an attacking move is likely to pan out, in terms of both how one team is faring in possession and another out of possession.

Modern football is all about space. For a defending team, it is about limiting as much space as possible. For a team attacking in possession, it is about finding space in the correct areas in several ways to create chances that lead to shots on goal.

The battle for finding space in the middle of the pitch is becoming football’s most important tactical tussle.

The reason I want to particularly focus on the fight in searching for and limiting space in central spaces is because that’s where most of the danger lies.

A team can play the ball wide to a winger and look to cause problems through that avenue, but a team finding space in front of goal is much more dangerous.

If a midfielder receives under pressure, manages to turn and dribble his way past the centre circle, he’s managed to reach an opponent’s half in a dangerous area.

Currently, what we’re seeing across different leagues in Europe is teams utilising differing methods of trying to find that all-important central space and the effects of said methods.

Getting the ball smoothly from A to B starting from the back is a representation of what a team does on the training ground but also, how they want to attack and pick the lock of a defensive setup to find gaps centrally.

In this piece I will be discussing the back and forth between teams in terms of:

- The methods currently used to stop teams progressing the ball centrally from defence to attack

- What teams are doing in response to get around these methods

- The importance of rotations

- The direct route

Man-to-man pressing and marking central midfield pivots

Ever since I started writing analytical pieces, I must have spoken about teams marking central midfield pivots every week.

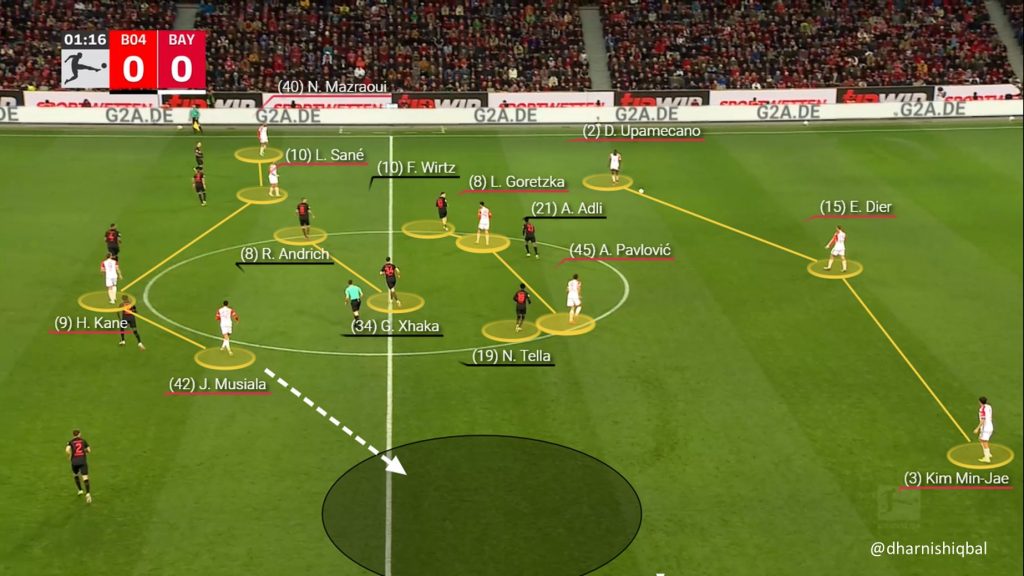

In the example below, Bayer Leverkusen’s approach out of possession completely stifled Bayern Munich. Of course, Munich are a team that under Thomas Tuchel are finding it hard to find pace and rhythm in attack generally, but against Leverkusen it was Alonso’s approach out of possession that quelled Bayern.

Leverkusen have overloaded the centre circle. As Bayern build up in a back three, Leverkusen are unconcerned with pressing the defence as the focus remains on making sure neither Leon Goretzka nor Aleksander Pavlovic receive the ball.

It helps Alonso was playing a system that used a back five, but the Spaniard clearly instructed forwards Florian Wirtz, Nathan Tella and Amine Adli to tuck in to narrow the centre of the pitch as much as possible.

By clogging the middle of the pitch, it cuts off a reasonable pass to Goretzka or Pavlovic: they can’t receive, turn, and play in the forwards as Leverkusen’s attackers and midfield are keeping the distances between them at a minimum.

As a result of this, Eric Dier is forced to look to go long and wide to a winger. We’ll discuss this later as an alternative option, but if you’re forcing teams wide rather than having a midfielder receive from defence, you lower the chance of a ball in behind to a striker.

The important aspect to note is the work of Leverkusen’s forwards to tuck in and narrow the centre surrounding Bayern Munich’s midfielders.

Without the work of the forwards, Leverkusen could face an alternative situation where they are tempted to press Bayern’s defence which would open gaps.

As if Goretzka was able to receive in space for instance and turn, the defence would feel the need to come out and engage to close him down, increasing the distances in their back five.

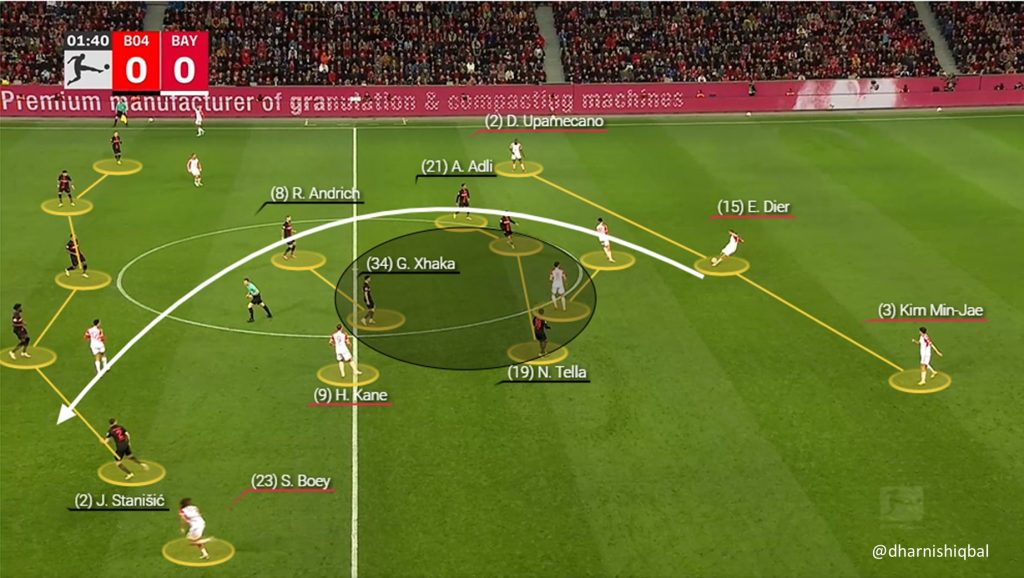

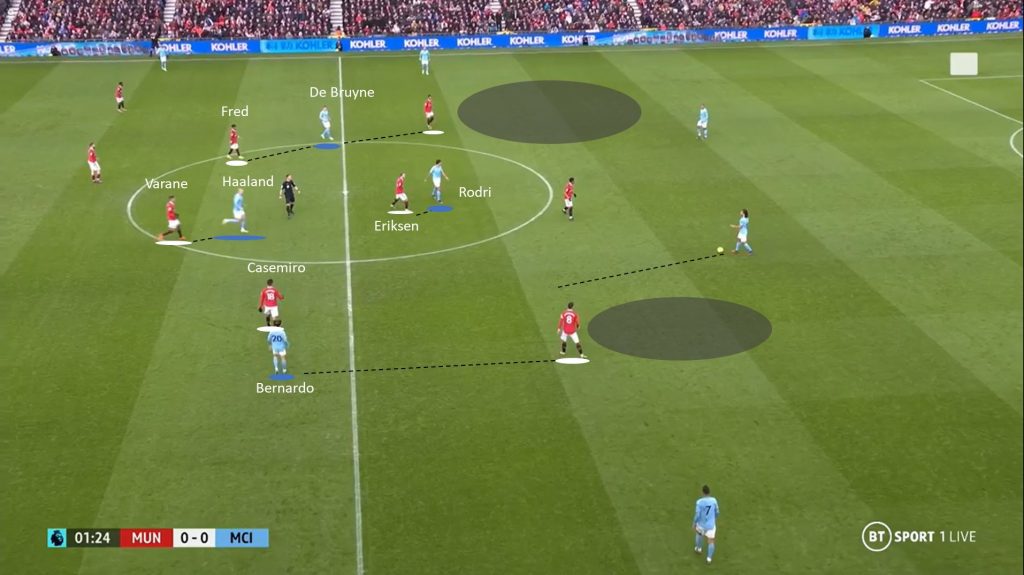

Manchester United were a team under Erik ten Hag that were particularly good at doing this last season.

The distances between the forward line, midfield and even Raphael Varane who has dropped in to track Haaland are very short. It cuts off the passing lanes to the advanced midfielders and with the wingers tucked into the half-spaces, it narrows the pitch meaning City can’t build up through the middle. If the pass is given to Bernardo Silva or Kevin de Bruyne, a winger in Fernandes or Rashford can aid in closing them down.

Contrastingly, it has been interesting to see the change in United’s structure this season as opposed to last and how much they have been exposed time and time again. This has been because of a switch from Ten Hag to unsuccessfully press higher up the pitch whilst teams have exploited his insistence of continuing to use man-marking.

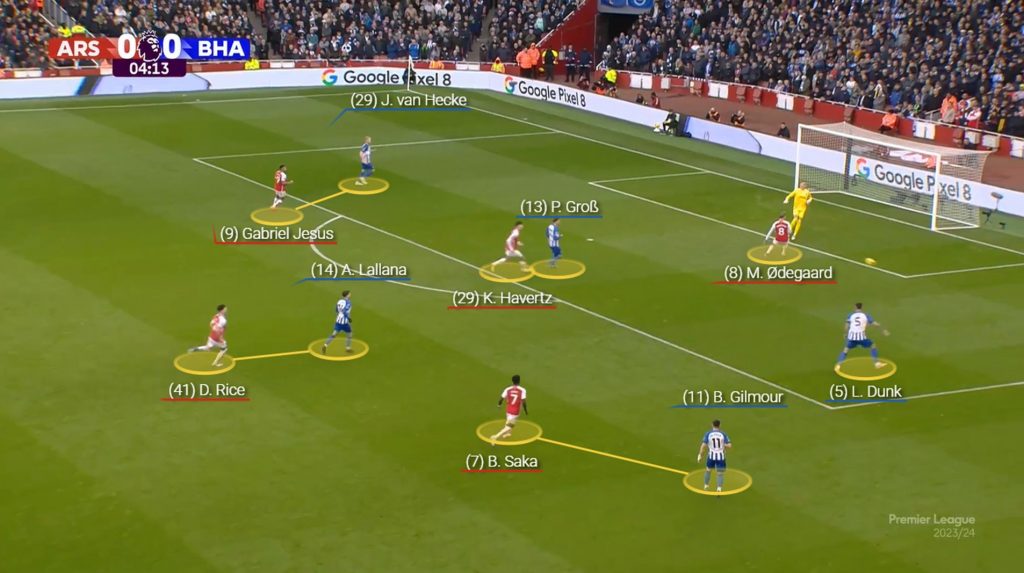

Arsenal, on the other hand, have been an example of a team excellent at being able to halt team progression by marking the central midfielders high up the pitch but pressing with more intensity, a braver way of cutting off progression in the middle which turns it into an advantage.

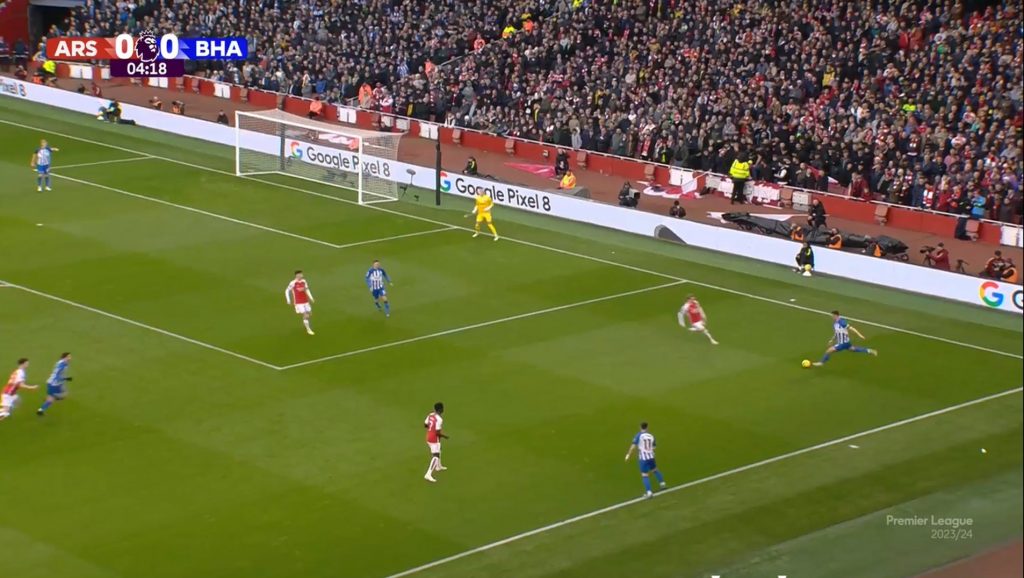

Against a team with one of the best build-ups in the world (Brighton) Arsenal stopped their progression, which is normally mobile and flexible, with Havertz marking Pascal Gross and Bukayo Saka marking Billy Gilmour.

This is one example of a team in Brighton attempting to do the absolute correct thing when faced with stubborn man-marking: moving as much as possible. Gilmour is attempting to pull wide and Gross short, with Lallana also dropping in to be a passing option, but the intensity of Arsenal’s press was such, Lewis Dunk was simply forced to go long, which whilst always a viable option in a De Zerbi team isn’t exactly plan A.

This was one particular example of an out-of-possession approach to cut off the supply lines to the midfielders whilst aggressively pressing Brighton deep in their half. It was effective because Arsenal had committed players in the press even if forwards like Mitoma dropped, Gabriel would follow.

Despite Brighton coming up with the correct plan to try to pull Arsenal wide or drop more numbers in build-up to aid progression, the commitment of each player to pick up the nearest one e.g. Saka on Gilmour even though he was picking the ball up wide, is what stopped Brighton from punching the ball through to their attackers successfully, despite Brighton’s players responding correctly with their movement.

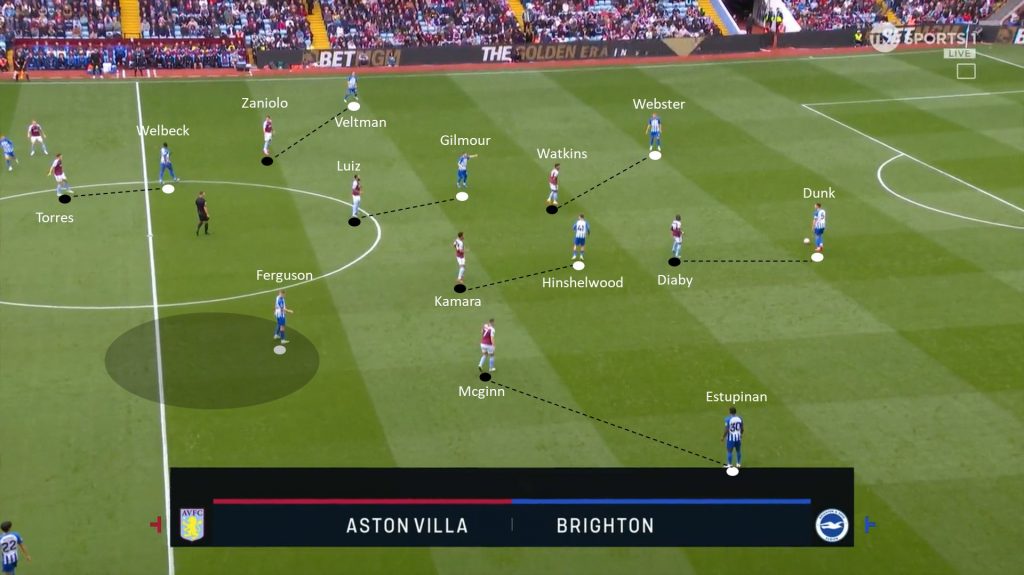

Against Aston Villa away, De Zerbi came up against Unai Emery who used Ollie Watkins and Moussa Diaby to drop off and form a box around Josh Hinshelwood and Billy Gilmour. Doubly, the work of Villa’s front two was effective because it meant Villa didn’t press Brighton, instead decreasing the space in which Gilmour and Hinshelwood were operating in.

Brighton are a team that thrives when being pressed, using it to their advantage to then pass through the spaces in between them. In Villa’s case, Watkins and Diaby specifically staying central was key as sometimes Diaby would drop off himself to mark Hinshelwood, which is the better decision as opposed to taking the bait and going wide to press Dunk.

The response to limiting central space

A team needs to be extremely well-disciplined without the ball to narrow central space. Arsenal, for instance, are one of the best teams in the world out of possession.

However, there are instances where teams can use players marking their central pivots to their advantage to find space. A common way to do this is by finding spaces on the edges of the midfield two in the half-spaces using advanced midfielders.

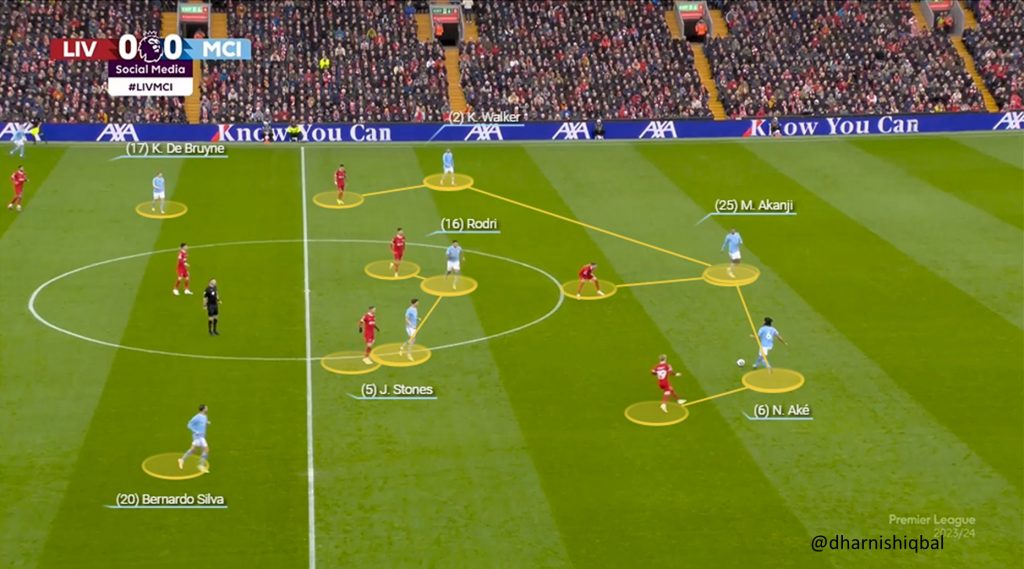

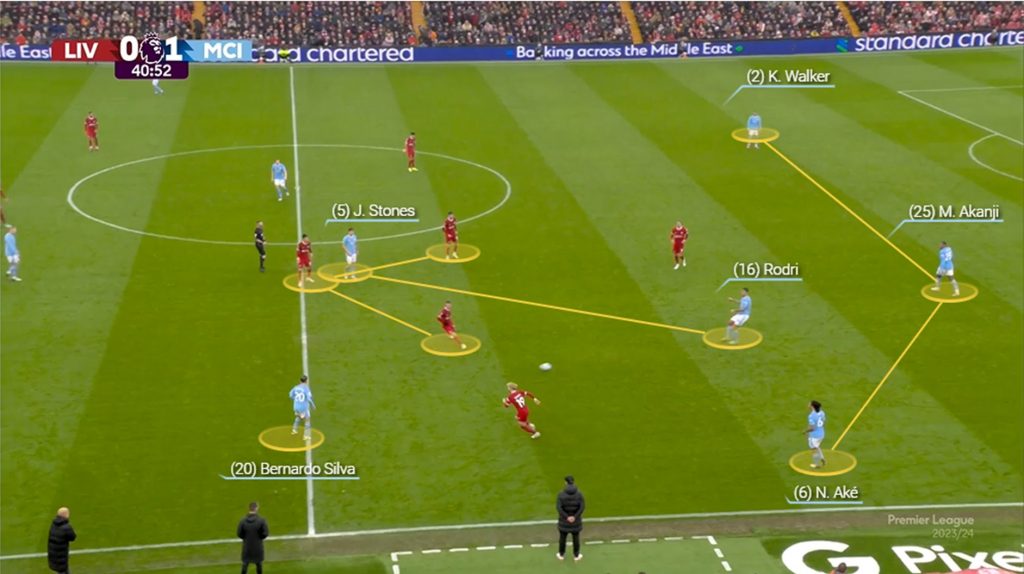

Against Liverpool, Manchester City found joy early on as they allowed Bernardo Silva and Kevin de Bruyne to float in the half-spaces. By spreading their back three wide, it enticed Liverpool’s front line to press with two midfielders marking Rodri and Stones.

As Mac Allister and Szoboszlai marked Rodri and Stones, with the forwards pressing City’s back line, it meant the defence could slip the ball through to Bernardo and De Bruyne on either side of Wataru Endo.

The fundamental response to your midfield being marked off is creating situations where you force the opposition’s block to be pulled around. City did this well by pushing their back three as far wide as possible, enticing Liverpool’s attack to press and increasing the distances between them and Liverpool’s midfield, then finding the advanced midfielders.

To get the ball from defence into attack, solving the conundrum of your midfield pivot marked, what we’ve seen teams do is drop a winger or striker short into build-up dragging players with them.

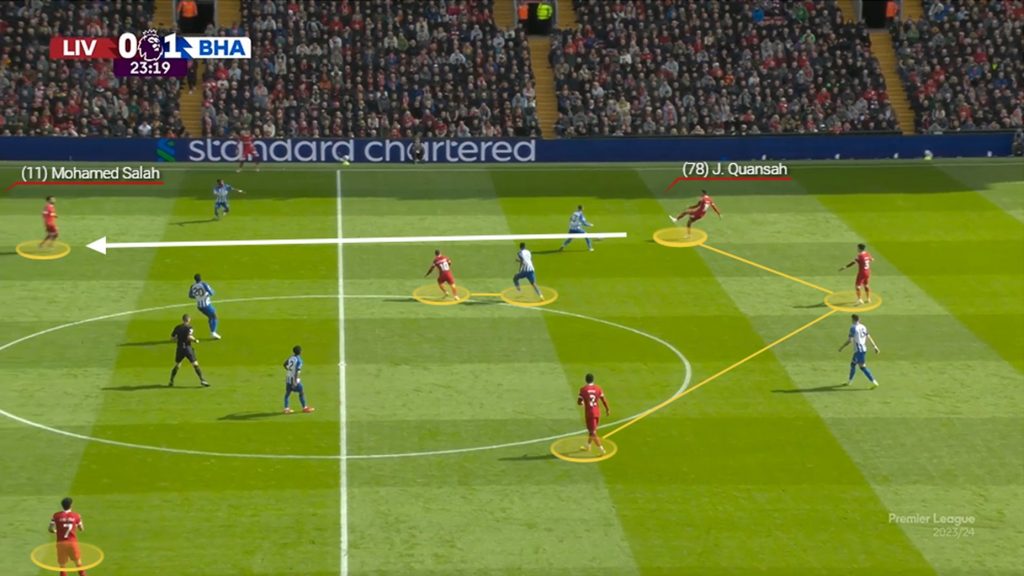

Liverpool have done it all season. With Mac Allister and Joe Gomez as an inverted full-back and Endo as part of the back three, the pass directly into Salah once Gross presses Quansah means the Egyptian can receive, turn and play it wide.

The addition of an inverted full-back in Gomez creates a headache because even with Baleba (20) going across to Salah, Tariq Lamptey has to stay in the middle to track Gomez who is part of the midfield.

The importance of rotations

How rotations in an attacking setup fit into all of this is crucial. By having a flexible system that is constantly changing with players keeping the same shape but occupying different positions, it moves a defensive block around as they struggle to keep up with marking players.

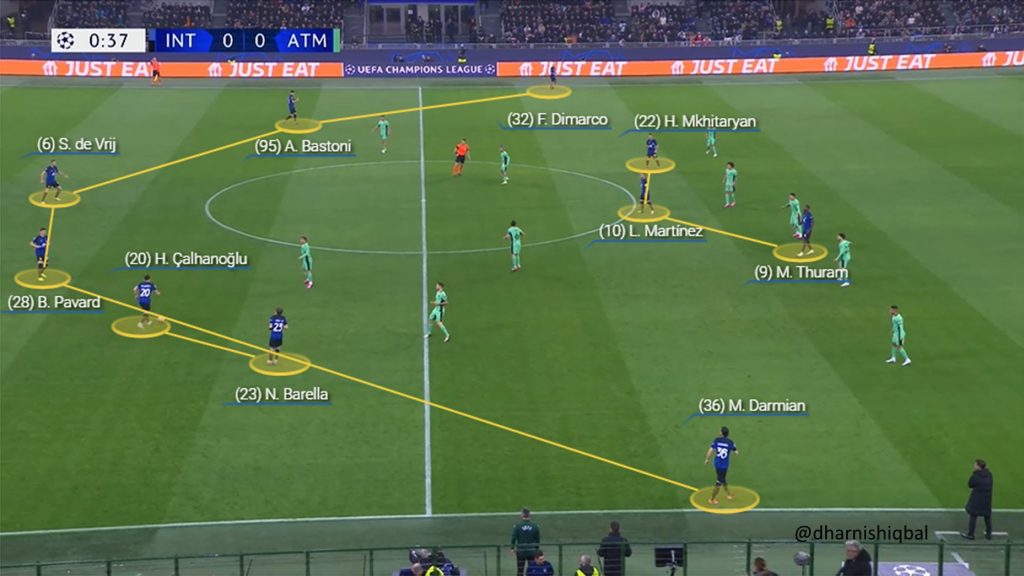

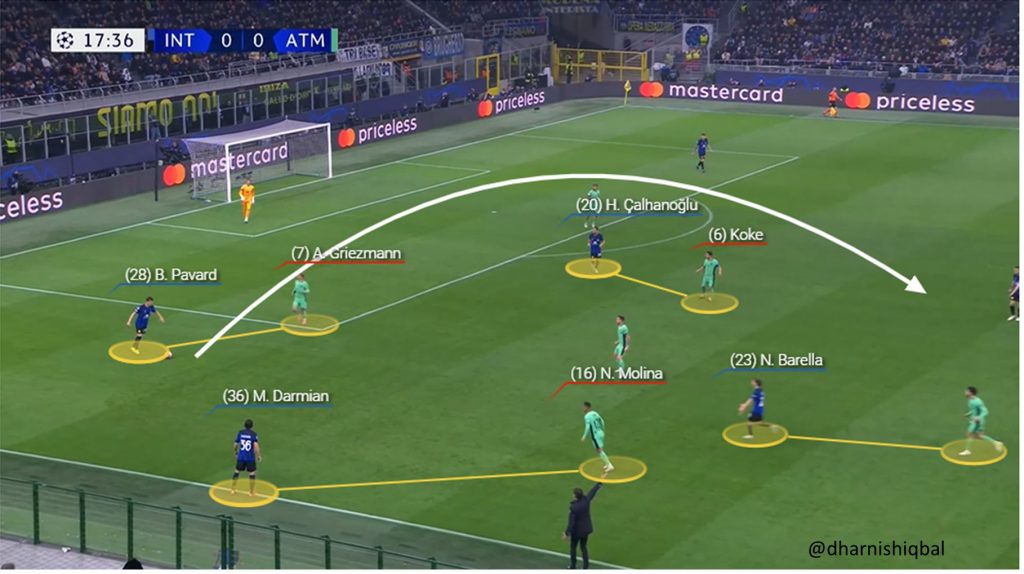

With Inter Milan, two central midfielders Nico Barella and Hakan Calhanoglu have dropped deep to receive the ball from the back three whilst the full-backs are pushed up high and wide.

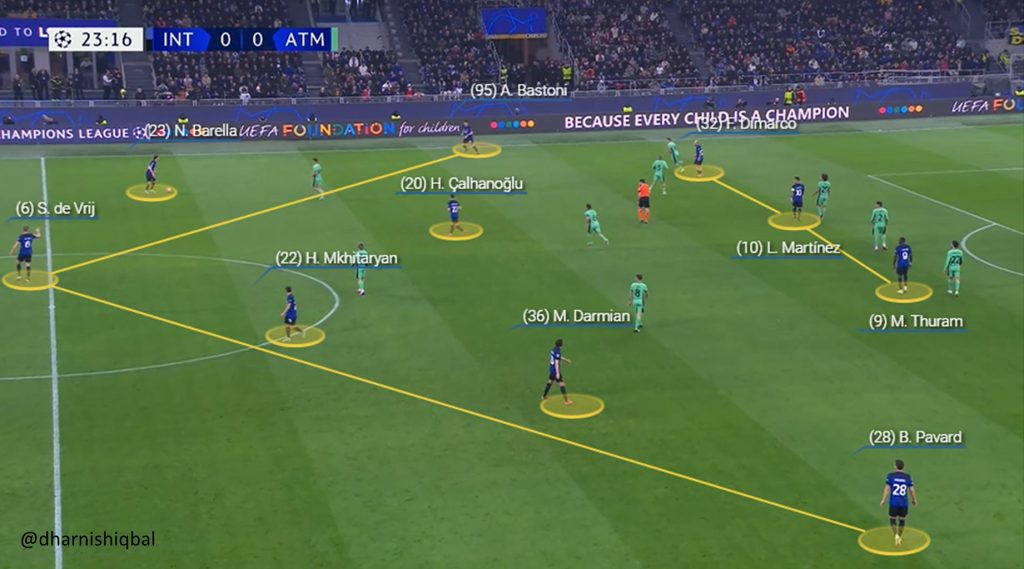

But in another minute of the game, look at where all the players have ended up. Benjamin Pavard and Alessandro Bastoni are pushed up high and wide as the centre-backs to provide width.

Two midfielders in Barella and Henrik Mkhitaryan are slightly deeper in build-up with Calhanoglu a little advanced and Matteo Darmian is now taking the role of a midfielder whilst Federico Dimarco is pushed up in the attack.

The rotations are such that if Atletico Madrid were to try and squeeze the space in the middle they would increase the space wide to Pavard and Bastoni.

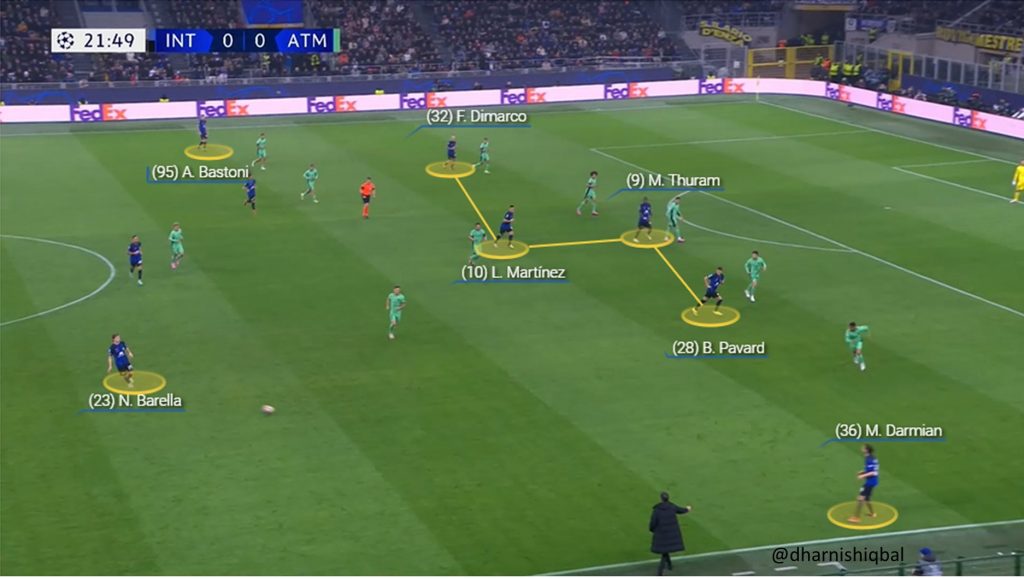

It’s harder to mark against rotations as players end up in positions you wouldn’t normally deal with. As below Pavard as a centre-back is pushed up and occupying Atletico’s defensive line.

This match was a prime example from Inter as to how to bypass a midfield pivot being marked through the use of their players having the license to push up and attack space even if they were a centre-back or full-back.

The Direct Route

There is also the option to go for the long ball directly from defence and play it over the top of a team’s marking system.

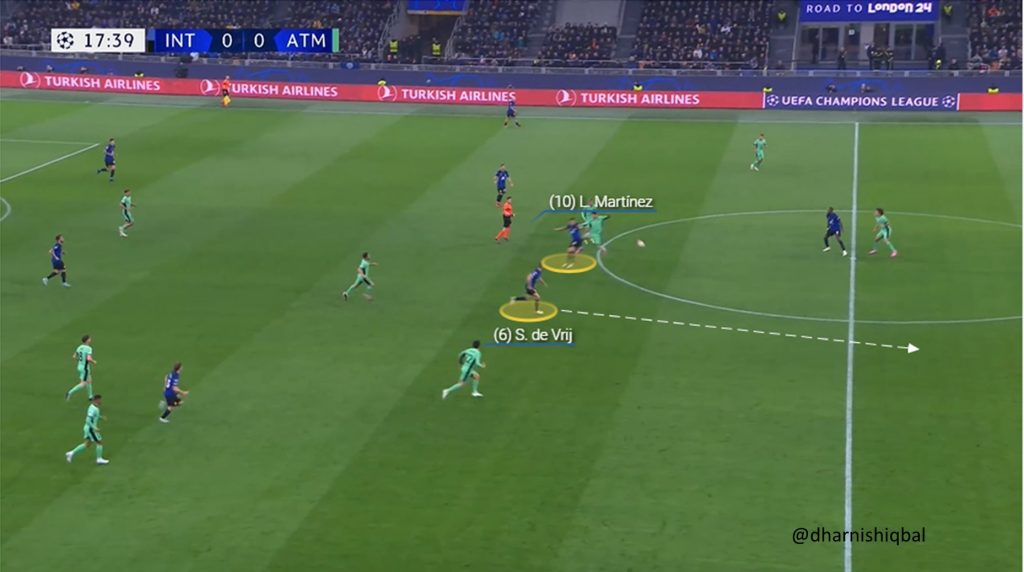

As Atletico Madrid have pushed up the pitch to go man for man, Pavard can play it long to Lautaro Martinez dropping in who flicks it on for Stefan de Vrij. Martinez’s flick around the corner also sucks an Atletico defender with him who needs to engage in the duel.

When he is unable to win it, Inter have opened Atletico up.

Aston Villa are a team that frequently use the tactic of utilising a team’s press to their advantage, wasting no time to play it directly over the top of a front-line pressing and the midfielders attempting to mark off their central midfield pivot (Luiz 6 and Kamara 44).

This is also effective for Villa because the ‘wide’ forwards, drift centrally often like McGinn to receive and become an extra option in midfield.

Villa are a team that rehearses and makes use of the direct route as normally if a team is looking to play a wide winger long, it is probably what the defending team out of possession prefers.

You would much rather take your chances with a team playing it wide to the winger who is tasked with taking on a full-back. However, if you have wingers who specialise in taking players on e.g. Rafael Leao at AC Milan it can be a dangerous tactic.

Even still, you would much rather compete aerially for duels as the ball goes long to the striker or 1v1 against a winger rather than concede space centrally on the floor.

There is a likelihood the aerial route would be less dangerous but it gets the ball up the pitch quicker and can bypass players going over the top of a press.

Conclusion

Football has evolved dramatically in terms of the methods used to score goals. What appears to be getting clearer is the differing ways used to get the ball out from defence up to attack are becoming more complex as out-of-possession ideas evolve in reaction to them.

How much space a team is getting centrally can not only determine the number of attacks and chances they produce, but it can also ultimately tell us who is sustaining the most pressure and is more likely to win the game.

Header image copyright IMAGO/Nderim Kaceli/LiveMedia