Casey Evans investigates how defining and analysing the difference between internal and external return on investment can lead to valuable insights about how to measure and value football academies

If there’s one thing that can still unanimously get fans on their feet, it’s an academy player making their debut.

It incites something primal within us; a desire to see a member of our tribe, “one of our own”, someone who owes they’re standing as a footballer to the club we support, make it on the biggest stage.

Clubs know this too, and they often wear their ‘academy players who have made it in the first team’ statistic like a badge of honour, but it would be short-sighted to say that this is the only reason that club’s like to see young players make the step up.

Nothing makes me prouder to be a Man United fan than the fact we’ve featured a homegrown player in every matchday squad for the last 86 years!

— Everything Man United (@EverythingMU_) January 8, 2024

Here’s to Alejandro Garnacho and Kobbie Mainoo helping to extend that record for the next 10+ years?? pic.twitter.com/tU1pxNymub

There is a huge financial benefit to investing in your academy. To begin with, according to Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, if academy players are sold, the club can bank the entirety of the players book value (as Chelsea fans are learning in real time) without subtracting any remaining acquisition costs associated with the player (i.e. the transfer fee to bring the player).

There is also the much more obvious benefit that if a teenage midfielder is good enough to make an impact in the starting XI in the Premier League, you don’t need to spend £50m+ and agree to a huge wage packet to fill the position.

Ultimately though, these are the ideal end points of a long and rocky road. Not every player is going to be sold for a massive fee, nor are they all going to make it in the first team.

However, while many fans and even clubs are focused on the bigger picture, there is still value to be found in giving these players’ appearances even if they don’t end up ‘making it’. One way to appreciate this is to consider internal versus external returns.

Internal return-on-investment (ROI) in football academies refers to the unrealised value derived from savings on player salaries and the potential value of academy-produced players to the team, considering the cost it would take to replace them with similar talent. External ROI, on the other hand, refers to the realised value from selling academy-produced players to other clubs. While external ROI is more straightforward to measure, internal ROI requires assessing the cost savings on player salaries and evaluating the performance of academy graduates compared to potential replacements.

To illustrate the point, we have decided to look at Liverpool FC with data collected from Sky Sports (for team sheets), Capology and Salary Sport.

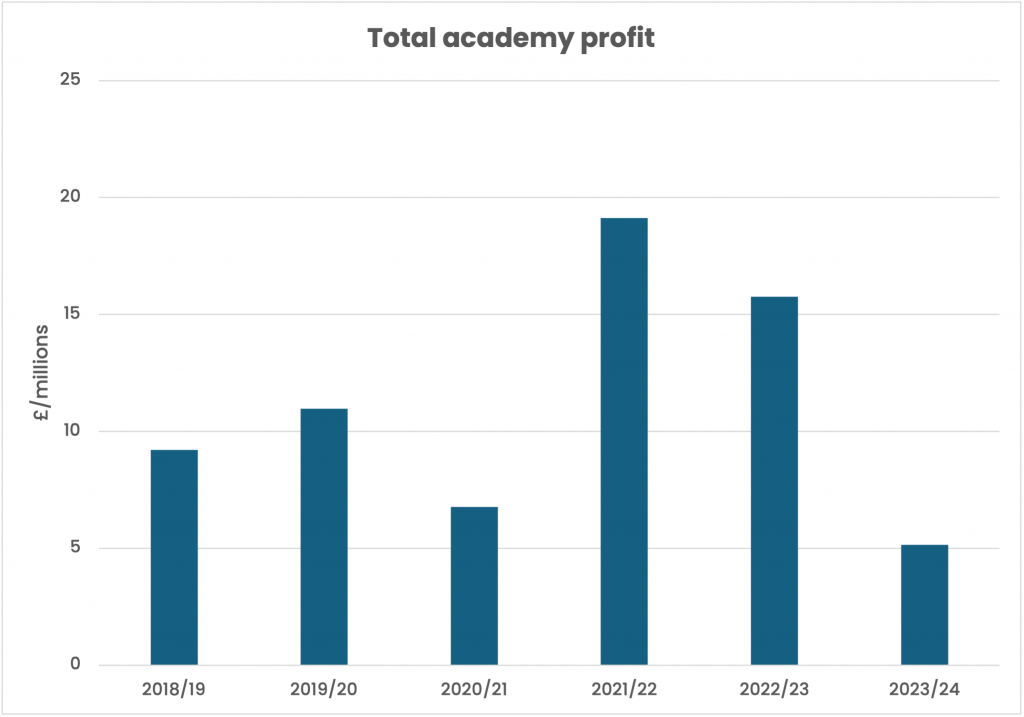

To begin with, let’s talk about Liverpool’s outlay because an academy is not ‘pure profit’ as many fans believe it to be: there are many costs behind the scenes.

Liverpool’s academy falls into Category 1, which means on top of hiring several high-quality qualified coaches and support staff and maintaining facilities to an elite standard, they also have to invest a minimum amount of money into the academy each year.

According to the Elite Player Performance Plan (2012) which introduced the category system, clubs in Category 1 must spend a minimum of £2.5m a year on their academies.

Some clubs will obviously spend more to separate themselves from the pack with individual academy complexes and even more support staff, but on average, Category 1 clubs across the Premier League will spend in the region of £3.5m.

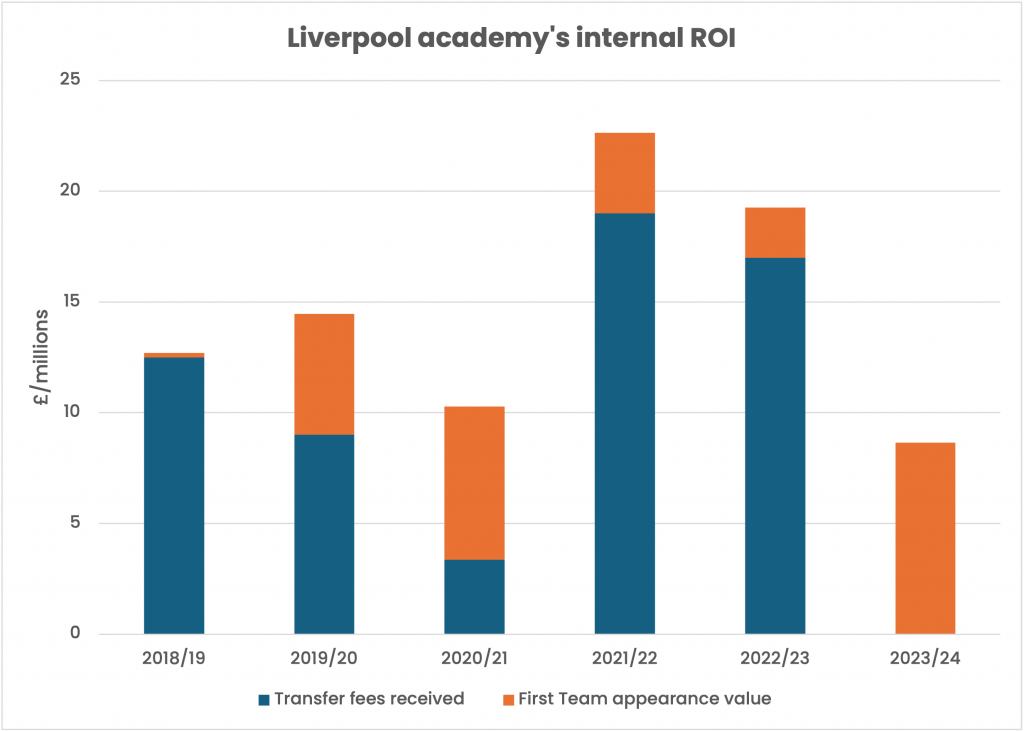

So, if we consider that that is the starting cost, we can now look at ROI. We gathered together appearance, salary, and transfer data for the last six seasons.

Firstly, you can see that in only two seasons, 2020/21 (the COVID season) and this season (yet to finish), have Liverpool’s academy incomes been generated more by player wage replacement than by outgoing transfer activity. Liverpool have also generated plus £10 million in player sales from their academy in three of six seasons, meaning that their academy has already generated good surplus profit, even before internal ROI is factored in. Jurgen Klopp’s side has received some impressive fees in the past for their players: Nottingham Forest paid £17m for Neco Williams last summer and the year before Fulham paid £12m for Harry Wilson, while Union Berlin paid £6.5m for Taiwo Awoniyi.

That said, if we hone in on this season, you will notice that Liverpool’s academy transfer fees for the 23/24 season, their external ROI, sits at £0, which alongside their impressive record of academy appearances this season makes the club a perfect example for our point.

The absence of these sorts of fees this season allows us to focus on the academy’s internal ROI, the intrinsic value these young players bring to the team through the cost savings we mentioned above.

And so, using financial data from Capology, we have calculated the average wages per week of several positions across Liverpool’s first team, from CB to CF.

Academy players on average earn less than younger players who are signed from other clubs. For example, although a key part of Liverpool’s squad, Curtis Jones earns 15k a week, the same as the academy winger Ben Doak, despite making 17 appearances this season.

Therefore, the theory is simple: we can use this wage data to calculate how much Liverpool have saved by providing playing opportunities to their youth, instead of buying a player to fill that first team squad position, which then gives us a sense of the academy’s internal ROI.

It is worth noting that in this article we don’t go further to estimate average transfer fees for those supposed replacement players, which means that while wages will give a strong sense of academy internal ROI, the actual saving would be even higher.

Looking at each game to see which academy players played (academy players here omitted those who are already established first team players/signed a big extension contract) in each game this season, we then calculated the ‘savings’ that Liverpool made in wages playing these youth players over a first team earner.

With this in mind, 15 players qualify for analysis in the 2023/24 campaign to date (03/05, which is when this article was written).

Jarrell Quansah unsurprisingly provided Liverpool’s biggest internal ROI. The centre back, who made his first team debut in the club’s third game against Newcastle, has impressed throughout the season. The 21-year-old has made an appearance in over 54% of Liverpool’s games and made the club a return of £2.04m.

Close behind him is full back Conor Bradley. The young right back became indispensable for Liverpool’s after 30 games into the season, only missing two through injury; his minutes have been greatly reduced, though, since the return of Trent Alexander-Arnold. Despite playing seven fewer games than Quansah (22 compared to 30), he has nonetheless ‘saved’ Liverpool £1.79m due his lower wages of 10k per week.

The only other player to break £1m for internal ROI (and double figures in appearances) is central midfielder Bobby Clark.

Pound for pound, Liverpool’s biggest ‘saver’ (the gap between actual and average wages) is forward Jayden Danns. He has only played five games for Liverpool but with a measly wage of £220 per week he is saving Liverpool near enough the striker’s average wage (140k) every time he plays.

Moving away from the financials for a second, our analysis also uncovered trends surrounding when Klopp was playing his young players, therefore showing the peak saving points.

Of Liverpool’s opening 10 games, Klopp only played multiple young players in one fixture; against Leicester in the Carabao Cup. However, between Gameweek 32 and 42 this massively increased, with multiple players appearing in seven games. This is partially due to the club’s injury crisis, but also because of the number of cup matches at that point of the season. These numbers have returned to normal in recent weeks due to many key players returning from injury, but also Liverpool’s exit from all remaining cup competitions.

Throughout the season, up to 03/05/2024, Liverpool have played two or more academy prospects in 70% of their cup games. It should also be noted that the two games in which they have played the most academy prospects are cup matches as well: against Union Saint-Gilloise in the Europa League (7) and versus Southampton in the FA Cup (8).

Finally, of the games where zero youth prospects were played, 43% were in fixtures against teams that had finished in the top 8 spots during the 2022/23 season.

These trends give us a great insight into how a manager like Klopp, who has the reputation of giving youth a chance, chooses to deploy these players throughout the season.

Overall, the inclusion of academy prospects shows an internal ROI for Liverpool of £8.65m compared to if their 96 total appearances were taken up by first team players.

And here, with transfer fees also factored in, are Liverpool academy’s likely profits for the six year period we considered.

But what lessons can we take from this?

Firstly, it shows the value of trusting academy players to take up squad spots in lieu of spending a transfer fee and higher wages on new player. Not only is it more cost effective as FFP regulations become more restrictive, but there is a possibility that they could develop into first team regulars, like Quansah or Bradley, which saves even more down the line as they replace the cost of a starting player. This internal ROI therefore has the potential to grow considerably, given that the cost of player replacement tends to rise, both with the market and with the age of the player being replaced (up to and slightly past peak age, anyway).

In addition, players who feature regularly, like Neco Williams for example, are more likely to transition to gaining the club external ROI as well; first team appearances act as a very effective shop window, even if the player does not go on to cement their place. This means that the financial benefits of an academy prospect tend to improve on a game-by-game basis in both internal, and potential external, ROI.

Most fans will always advocate for the inclusion of “one of their own” players in first team squads (it comes with the territory of being a fan) for almost sentimental reasons, as an important pillar of the football experience and a reason for club pride. But with the game being ever more dominated by money, presenting the cold hard financials of academy players’ inclusion is important. Academy players’ internal and potential external ROI also guarantee that, if clubs measure this intelligently, the value of a player’s transition into the first team can be valued and that makes it more likely to occur.

Header image copyright IMAGO / /Paul Terry / Sportimage