Jamie Scott analyses the Champions League winning coach with work to do in Bavaria

Thomas Tuchel’s arrival at Bayern Munich has seen him replace Julian Nagelsmann, a similarly experimental, progressive German coach. Both coaches speak openly about their tactics, and it is clear to see how their teams have been coached to play the way they do. The transparency surrounding their tactics helps the viewer to see how their sides go from concept to execution. This is helpful for analysis and generating discussion. Additionally, the specific mesh of tactical facets that both coaches implement in their sides are generally ones which fall in line with modern tactics, but tweaked and with additional innovations. This article will explore how Thomas Tuchel will redirect Bayern Munich from a tactical perspective, following Julien Nagelsmann’s tenure. Running points of discussion will include width (minimum/maximum and their implications), degrees of strictness in respective systems, and positional play.

Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea

The tactical interest surrounding Thomas Tuchel’s spell at Chelsea may have dissipated after he was forced out with barely a whimper in Autumn 2022, but there were a large number of tactical elements of real interest in Tuchel’s spell at the bridge.

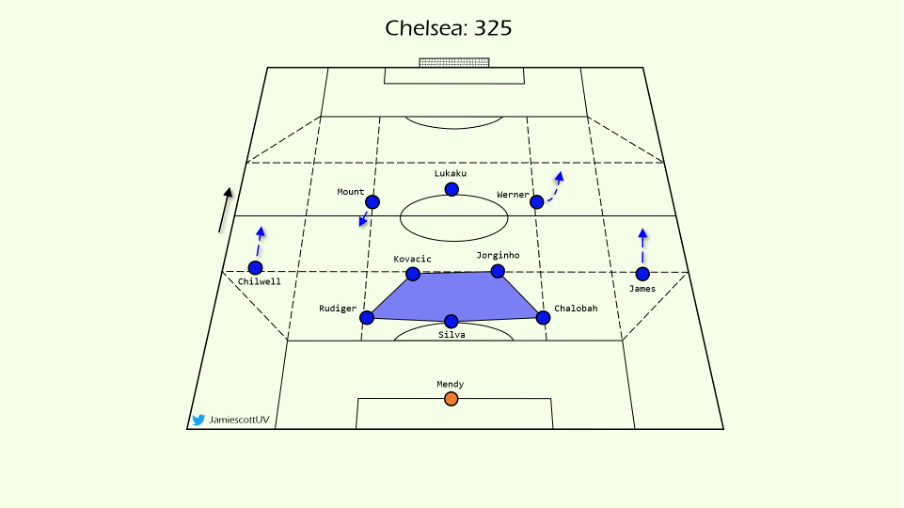

Tuchel set his Chelsea side up almost exclusively in a 325 formation. The back three and the double pivot in the midfield formed a 3-2 in build-up and this was mightily effective at times. The compactness of the 3-2 gave rise to quick, intricate passing from the back. Such short passes are typically safe, with the team having high ball retention when making a large volume of these passes, while the compactness of the build-up structure also gave Chelsea a strong rest-defence, with five players well positioned to defend and counter-press in the rare event of a turnover.

Chelsea’s security in build-up actually induced teams to press them. Playing a regular high block against Chelsea simply saw the defensive side’s first line of pressure get swamped, and subsequently overrun by Chelsea’s 3-2, which created a need to press. Furthermore, Chelsea’s high ball usage in central areas – almost a reliance on using the central zones to build up through – seemed to bait teams into pressing Chelsea. Chelsea actually topped the charts for ball retention and pressure attracted in their own defensive third in the 2021/22 season too. Whether this is a direct result of baiting pressure, or whether there is simply a relationship between Chelsea’s system and playing through pressure, we don’t know – but what we do know is that the 3-2 was generally very press-resistant, and effective in build-up, despite its lack of width.

On the topic of width, Chelsea were generally a narrow team in ball possession. They relied on central areas, and the half-spaces for build-up, progression, and creation. The wingbacks were often the sole members occupying the wide-zones, which was handy, because it meant Chelsea had a strong numerical presence in central areas, at most times. This allowed them to play through pressure, and overrun defensive set-ups, in most phases of play. Equally, if teams matched them in central areas, Chelsea could often find their wingbacks in 1v1 situations, by overloading (central areas) to isolate, or better, to find their wingbacks running into depth (space in behind) – a dynamic superiority.

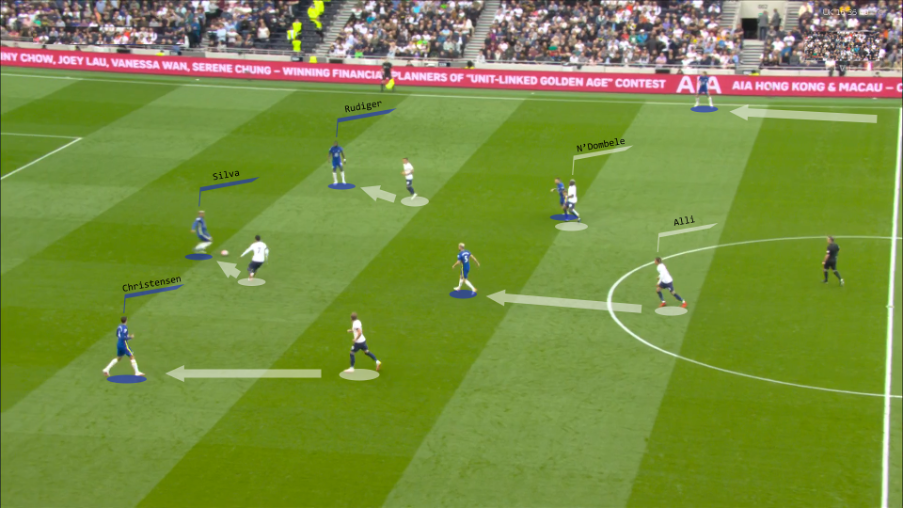

Nuno Espirito Santo’s Spurs posed Tuchel’s Chelsea an interesting battle in early 2021/22, by matching Chelsea’s 3-2 with a front three and a high midfield two. Spurs’ fullbacks also pressed Chelsea’s wingbacks, which made progressing out through the wide areas difficult too.

Tuchel made an astute tweak to the system at half-time though, which broke open the game for Chelsea. He brought in an extra midfielder, creating a midfield three. This meant that the two wider midfielders could take up wider positions, without compromising Chelsea’s core possession play (the back three and a #6 still remained central). Furthermore, in the context of the game, this change was highly advantageous, because the wide midfielders stretched Spurs’ first line of pressure. Passes could be made between the lines to find Jorginho, who could then orchestrate play.

With a 3-3 structure in build-up, it also meant that Chelsea could push their wingbacks into the attacking line, alongside their two strikers. This tactical adaptation by Tuchel highlighted that he is an astute coach, who still has problem-solving abilities – he isn’t merely set in his strict 3-2-5 framework.

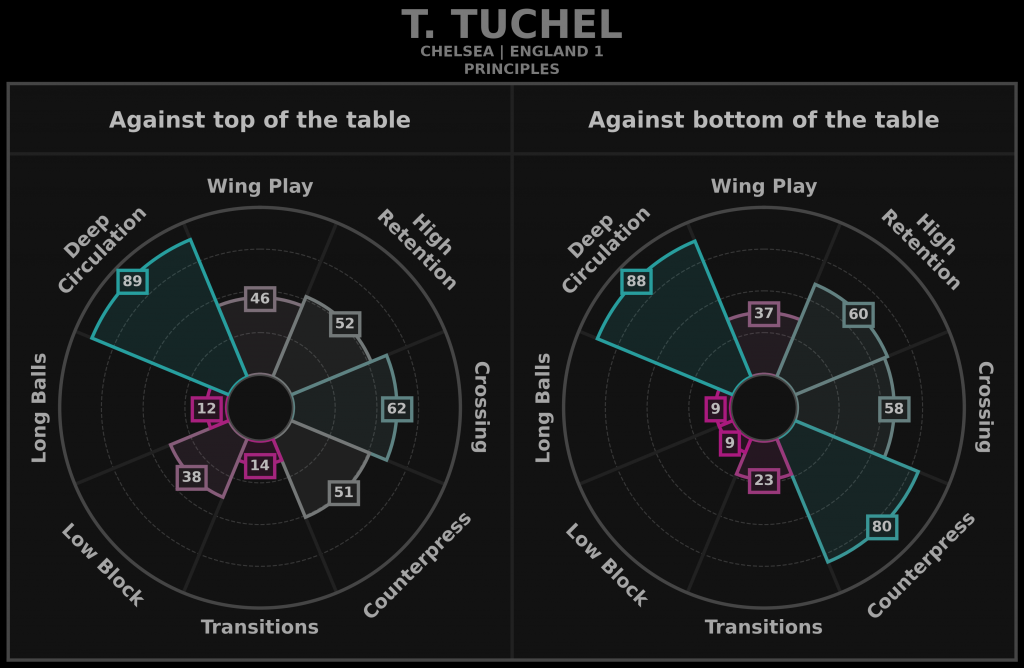

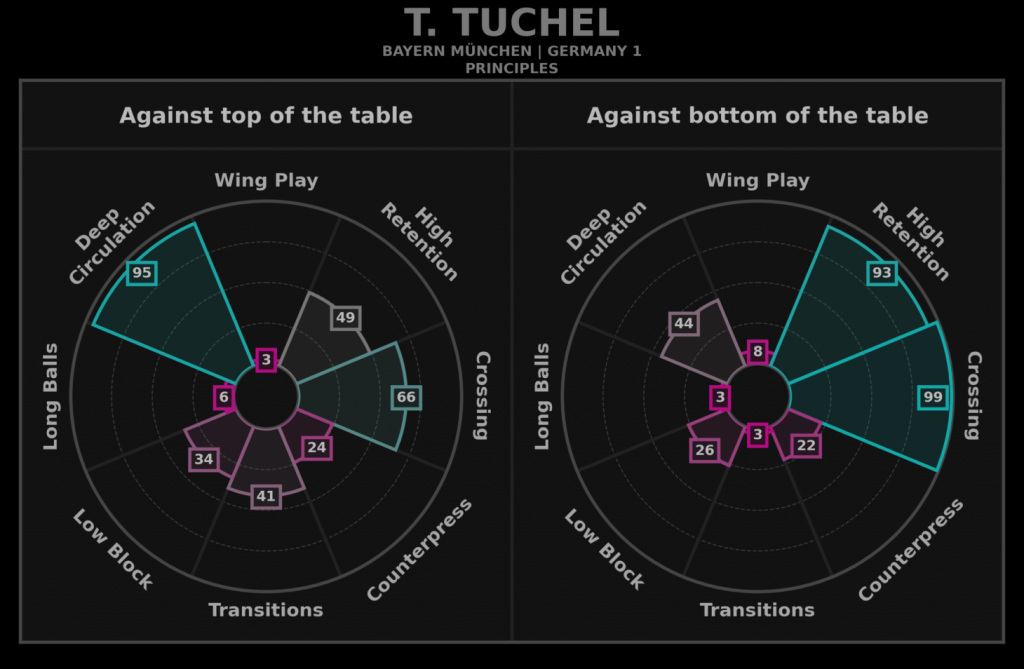

Tuchel’s 3-2-5 exhibited minimum width in build-up, and even in the instance of the 3-3-4, Chelsea still built with a relatively narrow structure. Conversely, in the attacking phase, Chelsea had a strong emphasis on maximum width (and subsequent vertical runs into depth from the wingbacks). Narrow build-up tends to create a compact structure and strong rest defence, while width in the attacking phase meant Chelsea could still stretch defensive blocks laterally. The combination of both minimum and maximum in a phase-dependant manner worked well at times, and gave Chelsea the best of both worlds. This is reflected in Tuchel’s Coach ID wheels, which show some use of crossing but less of a focus on wing play, which indicates that it is not a constant from build-up into the attacking phase. Conversely, the proclivity for deep circulation, which is reflected upon above, is obvious.

Nagelsmann’s Bayern

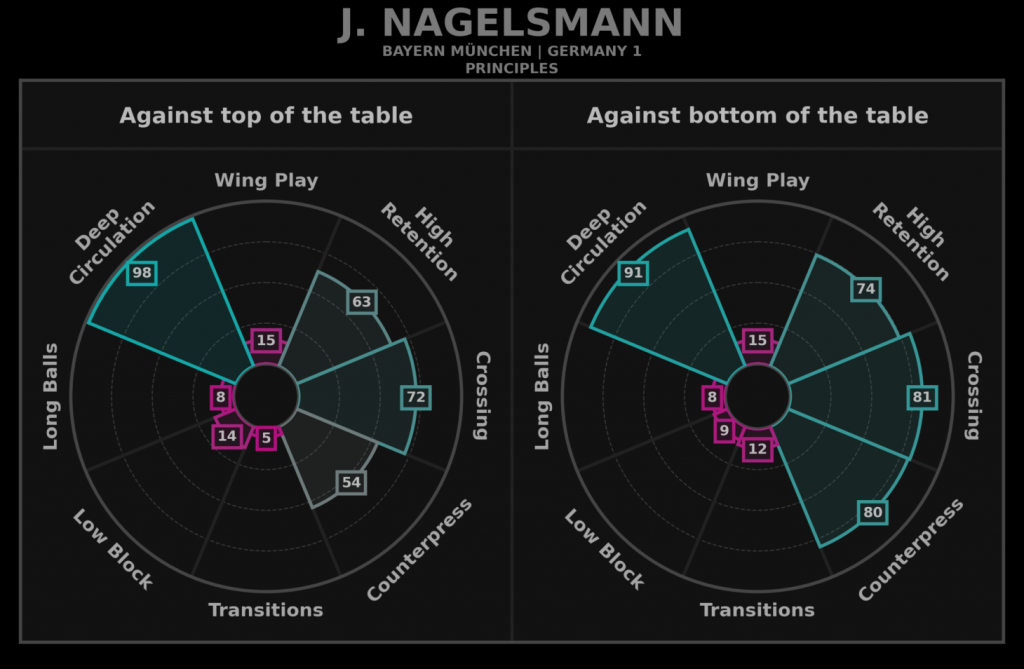

One of the trademark features of a Julian Nagelsmann side, is their use of minimum width at most times. This can, again, be seen from his Coach ID wheel, which shows once again that the concept of ‘wing play’, or width, and the output ‘crossing’ do not necessarily co-exist. Nagelsmann’s teams use minimum width, but cross frequently (this includes pull backs).

Nagelsmann teams build with a temporary back three (from a base back four, with one fullback advancing and the other inverting (although at Hoffenheim this was a genuine back three with wing backs). At Bayern, the build-up often consisted of ball playing centre-backs such as Upamecano looking to play through the lines centrally. Benjamin Pavard, the right back, was effectively an auxiliary centre-back performing the same function as Upamecano. With players like Muller occupying central attacking spaces, Bayern really looked to maximise their infiltration of high-threat central zones. While Bayern’s roster may have contained flying wingers such as Leroy Sane and Kingsley Coman, the former was often seen attacking central (or half-space) channels, as Bayern’s shape was quite narrow.

This isn’t to say there wasn’t wide space occupation – Alphonso Davies thundering down the left wing, for example. Much of Bayern’s play was narrow in relation to their players, not the pitch zones, however. If Davies exemplified maximum width on the left, the far side right winger would tuck in, to a great extent. The total width of the team was therefore still minimal. This is how a team can use crosses while still having minimal width. And while there are conceivable disadvantages to such a use of minimum width, the performance of Nagelsmann’s side was by no means shockingly bad – the strategy wasn’t inherently flawed. It is for that reason that the direction Tuchel will take at Bayern is interesting – we will see how much he changes in the short-term future.

Tuchel at Bayern

The stand-out feature of Tuchel’s early reign at Chelsea was his ability to raise the floor of his side so quickly. This was much akin to a typical Antonio Conte takeover at a club, where the simplicity of the system and the discipline of coached facets are typically very high, which is conducive to quick improvements in the team.

While Conte is very good at implementing automatisms in his sides, they are also prone to becoming very robotic, thus, easier to analyse and defend against after approximately 12-18 months. With Thomas Tuchel, this is less likely to be the case. Not only is Tuchel a great thinker of the game – he is constantly innovating, and his understanding of tactics from a pragmatic and philosophical perspective are both clearly outstanding, but Tuchel also allows much of his side to engage in problem-solving. Particularly in attacking phases, players playing under Tuchel have a reasonable amount of freedom to play. If Conte is a disciplinarian by trade, Tuchel is more of a self-reflective manager.

Tuchel has already implemented a couple of fundamental tactics – but not with the same level of rigidity that he did when he was at Chelsea. The rationale behind this may be because the players at Bayern are higher in quality, and therefore able to cope with more – but we don’t quite know yet. The foundations laid by such a manager like Julian Nagelsmann may well have raised the floor of the side from a tactical perspective anyway, so Tuchel is merely putting into action what he sees fit at this late stage of the season. Indeed, from his Coach ID wheel, we can see that Tuchel’s Bayern is almost identical in style to Nagelsmann’s except for a relative absence of counter-pressing.

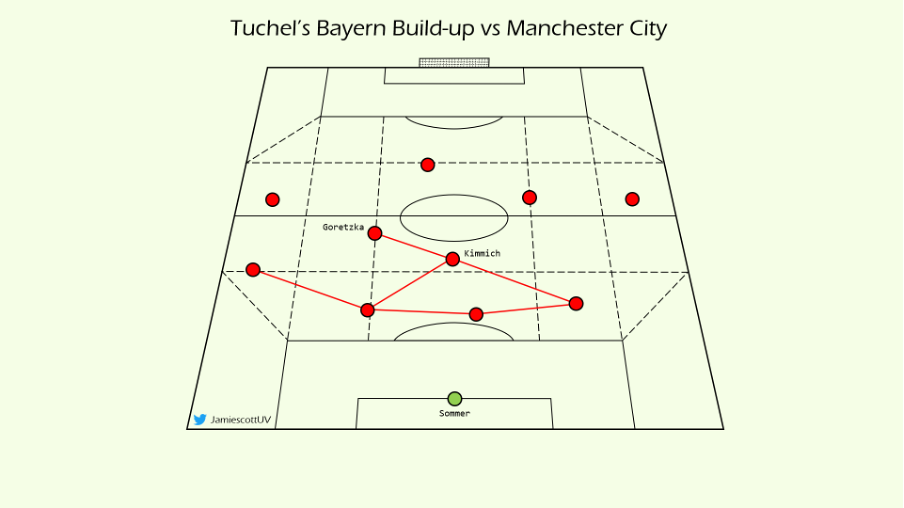

Bayern still play in a notably narrow shape at times in build-up, with both fullbacks inverting to join Kimmich in a 2-3 shape.

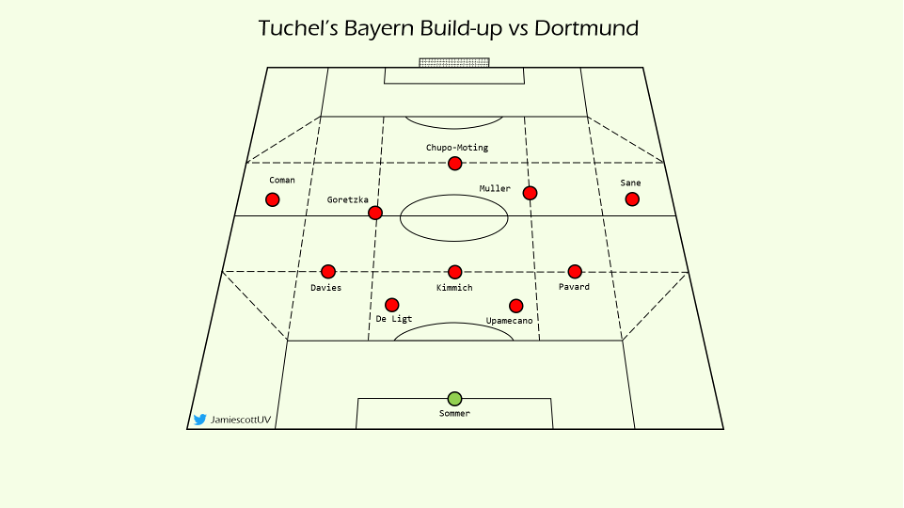

Bayern are by no means bound to this structure though. Against Dortmund in Tuchel’s first game, one or both fullbacks moved wider and higher to support the attack. Tuchel has always implanted wide and vertical runs, so with the wingers and at times the fullbacks making those movements, Bayern have strong wide threats. Joshua Kimmich was a juggernaut in midfield, making the most touches and controlling the game with relatively little central support – the #8s played high and in the half-spaces, while the fullbacks weren’t omnipresent in build-up. There was certainly no ‘minimum width’ here, and it worked. Benjamin Pavard did have more of a proclivity to drop into the back line, creating a three with the two centre-backs, and with Davies pushing on down the left. This seems to be a remnant of what happened under Nagelsmann, where Pavard was often an auxiliary centre-back in build-up (it is also a representation of his own personal game, as much more of a wide centre-back-style fullback). Tuchel therefore also seemed to be quite lenient with his players, allowing them to be more liberal with their positions, and be encouraged to ‘problem solve’.

This emphasis on more width saw things unravel versus Manchester City however. Bayern were competitive over the two legs, and Tuchel’s set-up, given the circumstances, was more than reasonable. Unfortunately, the bigger distances between players in build-up saw Bayern come under pressure, and Upamecano was the unfortunate embodiment of this struggle. It felt as though his somewhat panicked defending was also a derivation of his lack of comfort on the ball – perhaps due to the new system, but more likely due to the new difficulties posed by larger player spacing. This is a surprise from the coaching perspective, as Tuchel was renowned for his compact 3-2 in build-up at Chelsea – and he actually had great success versus Pep’s City. The tie was decided on such moments, and City were clinical in pressing, attacking transitions, and when finishing key chances. Joshua Kimmich was unable to control the game by himself, and Bayern were overrun at times.

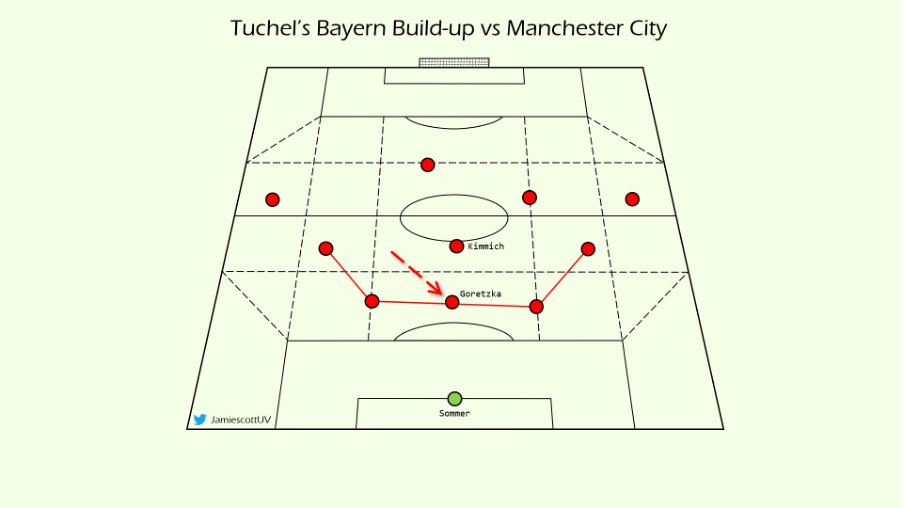

Goretzka was instructed to drop deeper, to assist the first line of build-up at times, in order to help cope with Manchester City’s high block and press. The 3-3 structure that was subsequently created was much akin to the adaptation Tuchel made against Spurs in 2021, where the use of a 3-3 helped stretch Spurs’ block and open progressive passing lanes through the lines. The wider spacing from the midfield line also meant that passes were angled diagonally, rather than in a vertical line, which is also more ideal for optimal play.

Unfortunately, on this occasion, City’s block and subsequent press was just too sharp and aggressive – and Bayern struggled to completely control the game in possession, as the passing distances in build-up were fairly long. Some of Bayern’s players also struggled with the increased amount of freedom to problem-solve, against such an organised City side.

Conclusion

Thomas Tuchel joined Bayern at a tricky, inopportune time and although it seems as though the Bavarians will win the title (slightly marred by the controversy around Dortmund’s non-penalty at Bochum), he will need longer to see the fruits of his labour. Bayern’s squad quality, and the tactical foundations left by Nagelsmann, are good, and it will be very interesting to see how much of both Tuchel retains as he has more time to implement his tactical principles. The move to use width more openly is perhaps surprising, given Bayern were a typically narrow side under Nagelsmann, and Tuchel’s Chelsea were extremely compact in their trademark 3-2 build-up structure.

Tuchel still seems to be very thoughtful and engaged from a tactical perspective, making astute and logical tweaks to his side in games – but with the small sample size and with limited time in charge, these tweaks haven’t been overly successful in outcome yet. Tuchel is a smart appointment by Bayern, and despite the surprising timing of the move to get him, there is every chance he will be a success in the next few years. His team will offer better control in games, and with the player quality available, Bayern could feasibly be even more dominant in the upcoming season.

Header image copyright: IMAGO / Ulmer/Teamfoto