Jamie Scott looks at the approach used by Pep Guardiola and others and asks whether the dominant tactical ideology of elite football has had its day

Juego de Posicion (‘positional play’) is a commonly used systematic ideology for a team to play within. Players are encouraged to occupy certain zones on the pitch, which advantage the team’s structure and individual dynamics. This strategy has worked well in modern football – most notably with Guardiola’s recent sides enjoying almost unbridled domination in domestic football for the last ten years or so.

Current trends suggest that the use of positional play ideologies can be limiting for teams, however. Opposition sides are better at solving the conundrums that positional play systems pose, while the generalised improvement of defensive structures has caused implications for the specific superiorities positional play systems are often conducive to generating.

This article will use Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City as a case study to discuss why the demands on positional play systems are greater than ever, and merely focussing on having good positioning isn’t enough to pick up points at the same consistency.

Why was Juego de Posicion effective in build-up?

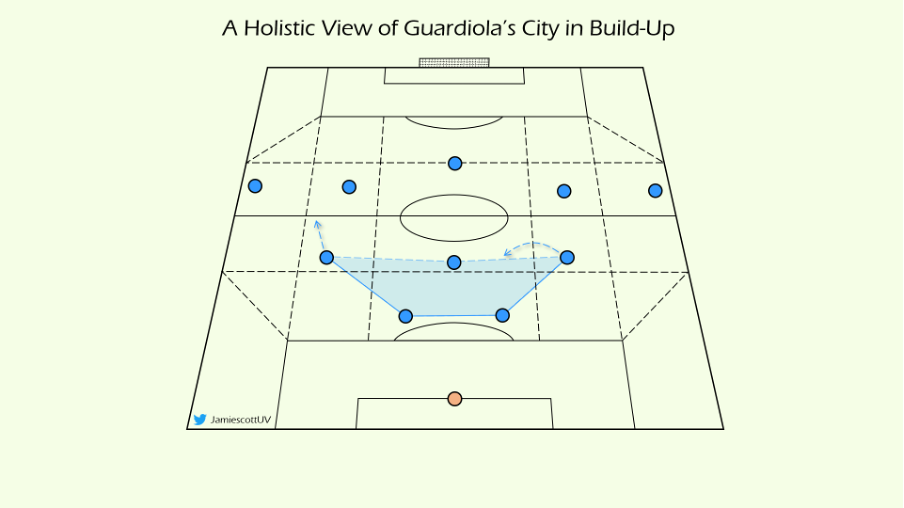

There are many aspects to positional play systems that made (and can still make) them so effective. Positional play systems are designed to optimise many facets of in-possession and transition phases. In build-up, players are spaced with short distances between each other, because short passes have a reduced likelihood of resulting in a turnover; short passes are easier to execute consistently. Furthermore, because the players are in such close proximity, the team’s rest defence is compact. Additionally, having players spaced out ideally, but in a compact shape, means that the team can create overloads around the ball without sacrificing ideal team dynamics – there isn’t a feeling that Guardiola’s Manchester City’s typical build-up is overly congested, for example.

Guardiola has implemented a number of different schemes in build-up, all of which have exemplified how positional play can be highly beneficial. We have seen the 2-3 structure, where both fullbacks take up a relatively inverted position, so City can control the first phase with the five players (the back four and the #6). Sometimes Guardiola has used a shape where one fullback would invert, and the other would push on, or sit in the back line (effectively a 3-2 shape). Infrequently, Guardiola has also used a more dynamic 424 shape, wherein the back four is quite deep and wide, and Bernardo Silva would join the double pivot. In such a circumstance, City were better suited to baiting pressure and playing through it in quite a direct manner.

Structure in build-up is generally advantageous, even when noting that teams are becoming better at facing positional play systems. Because many teams simply aren’t too scared of conceding territory or control in City’s build-up phase, City’s rigorous structure allows them to dominate. There isn’t too much of a concern that having such a disciplined shape will detract from optimal play, for example stripping players of the prerogative to have individual inspiration. Moreover, the lack of need for instantaneously creative, off-the-cuff actions simply enhances the clarity of which the players are performing with in the build-up. This further reduces ball loss and/or slow, stodgy build-up.

Interestingly though, while teams often settled into mid-low blocks, which effectively means they’re conceding competitiveness in the opposition’s build-up phase, other teams aim to disrupt their opposition’s build-up by implementing a high press. City could well have been particularly susceptible to a well-coached high press because it is so easy to see how City aim to play – not least because their positional play is so well defined, but also because Guardiola is the gold-standard of coaching. What we see on the field is most likely what Guardiola intended – there is little real variance week to week, and City are predictable because of this. If anything, their 424 shape, which is often utilised in games against notoriously strong pressers (such as Klopp’s Liverpool) or in periods in a game where City are being pressed high, is much less of a positional play line-up. The team is far more dynamic positionally, and reliant upon the press-resistance of Bernardo Silva in the #8 position. This observation certainly counters the view that positional play systems alone are enough in the immediate recent past of modern football.

Is Juego de Posicion effective in creative phases?

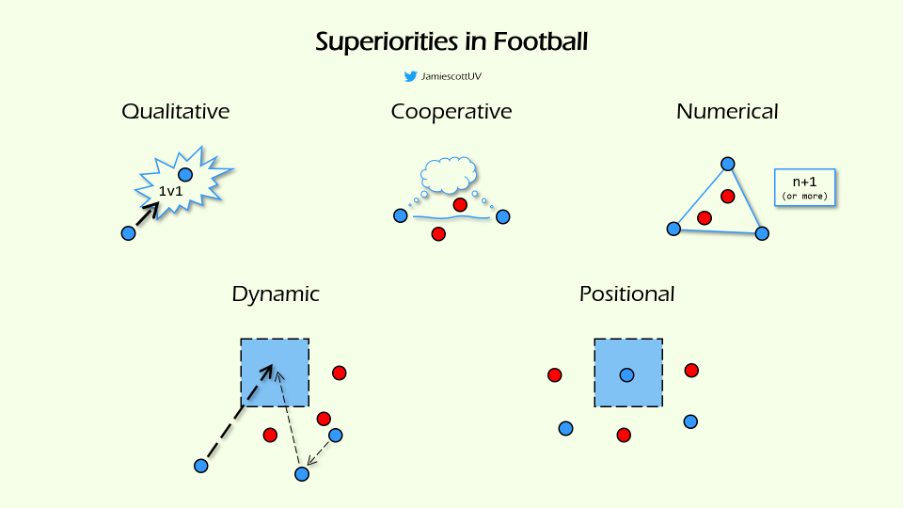

In attacking phases, Manchester City maintain a positional play approach. Their players are spaced according to good-practice positioning with an ideal number of players in each vertical and horizontal zone, so as to create favourable and repeatable attacking scenarios. City use rotations, and while this implies fluidity, rotations simply mean that players must all fill in the zones that are vacated by those who are endeavouring to create chances – it is very mechanical. Positional play often gives rise to superiorities – hypothetical favourable scenarios from which to create from. These superiorities are typically positional or dynamic superiorities.

An example of this was Manchester City accessing the half-spaces for De Bruyne or Cancelo to create from, or slotting a player into the cut-back zone to generate high xG chances. While Guardiola’s City broke points records by exploiting these positional superiorities, teams became savvy to this approach, and implemented defensive set-ups which negated the positional threat of Manchester City.

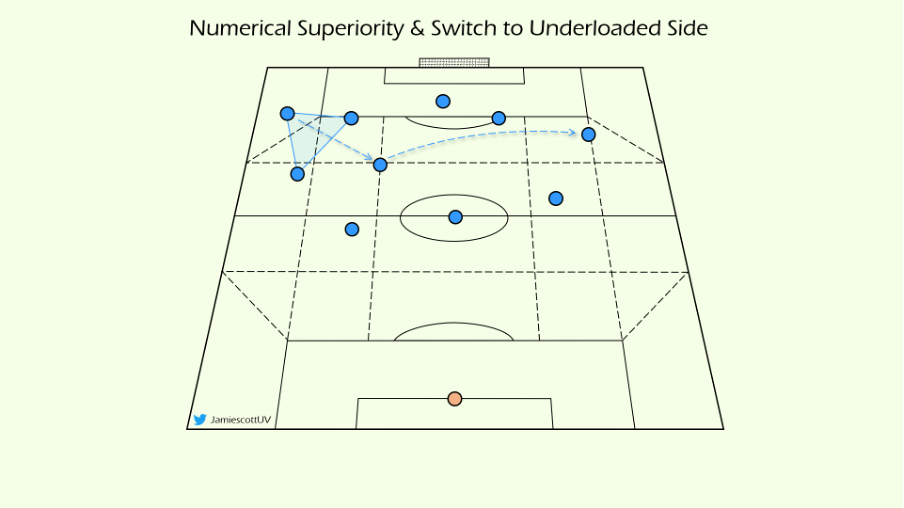

Other superiorities can also be created by positional play systems, naturally. Numerical superiorities in the form of overloads can often draw teams to defend one side of the pitch. City often recycle attacking play through their #6, Rodri, who immediately makes quick switches out to the underloaded side, where City can exploit the relative lack of defensive attention. Similarly, overloads down the line and in space often opened space for Joao Cancelo on the left, to whip crosses in.

One mode of superiority which is of particular interest when it comes to this article is qualitative superiorities (an individual superiority). Manchester City simply having better players than most (if not all) of their opponents makes this somewhat of a given for them, but good positional play does accentuate the potential of consistently accessing individual superiorities. City switching to find Mahrez in a 1v1 scenario, for example, is an instance of using positional play to find an individual superiority in the form of a favourable match-up.

This begs the question: where do we draw the line between attributing credit for the positional play system for being conducive to individual superiorities, and where individual brilliance is dragging the team to results despite the positional play system?

The concept of teams needing an ‘x-factor’ to get a cutting edge isn’t a new phenomenon, not least in recent tactical discourse, because automatism-heavy systems are also often reliant on individual brilliance in the attacking third. But due to the aforementioned factors, such as opposition defensive setups being especially primed to face Manchester City’s predictable positional play shape, reliance on individual superiorities is perhaps more pertinent than initially suggested.

Using Mahrez as an example, Guardiola often comes back to this player when the going gets tough – when he is reverting back to simpler iterations of his system – when he wants to control games in the most granular way possible. Mahrez is a tricky 1v1 winger with a great end-product, but the next question we can ask is: does the positional play system, which initially sought to catalyse play into accessing 1v1 scenarios, actually limit Mahrez in 1v1s? This question is quite convoluted, almost a spiralling of thoughts and ideas from one observation to the next, but in short, Mahrez does feel limited by the system. He doesn’t roam across the front line to devastating effect as he once did with Leicester – rather, he remains strictly on the right, receiving mainly to feet, at a standstill. He can beat players down the line, but is often induced by the system to cut in. Kyle Walker has even once said that he almost exclusively underlaps right-footed wingers on the right wing, and by extension, generally overlaps the left footed Mahrez on the right. Mahrez typically doesn’t have space to go down the line, and doesn’t have license to drift into the half-space to liberally – that’s Kevin De Bruyne’s zone. Suddenly, the idea of Mahrez having a sea of options in 1v1s doesn’t only seem to be incorrect, but quite the opposite of what the positional play system has induced.

Individual superiorities may well not be the individual ‘x-factor’ that positional play systems need in order to remain the tactical framework of choice at the elite level.

Conclusion

Guardiola himself has been on the record to say that having good fundamentals is never enough. What he seems to mean by this is that having a good positional play system isn’t sufficient – his team must always be evolving, changing, adapting. And the embodiment of this notion seems to be through Guardiola’s tweaks to the system – there have been many different embodiments of City’s positional play system.

What Guardiola perhaps isn’t so keen to admit is that there could always be a need for individual flair. Guardiola’s systems are typically all-encompassing, and his approach is generally disciplinarian. Players who can’t fit the system are ousted, irrespective of individual capabilities. This can often be limiting, particularly in the case of players with profound natural talent, who need a free environment and clear mind to play. With Guardiola’s anti-flair proclivities, and the developing tactical trends that suggest relying on systematic superiorities isn’t sufficient anymore (not least raw positional superiorities, or rudimentary dynamic superiorities anyway), the outlook for City looks ominous – something has to give, not least because City’s statement piece, the player who instils an element of anti-Guardiola, Erling Haaland, simply can’t keep scoring from any and every angle to ensure City have their x-factor.

They may need something more and something different in the not so distant future, or risk being left behind at the top.

Header image copyright: IMAGO / Xinhua