Jamie Scott analyses the Italian coach and his style of play and asks whether automatisms create more issues than they solve

On the spectrum from disciplinarian tactical play to freeform styles, automatisms are the most extreme iteration of the former. Automatisms supersede even the most rigid Juego de Pocision (JDP) styles of play in the discipline required to adhere to a specific tactical framework. But while there is now an expectation that the most successful teams will play with reproducible combinations and rigorous positioning, really automatism-heavy sides have not fared as well as less rigid teams. Purely automatism-based sides are rare, which makes analysing this small sample size hard, but Antonio Conte’s teams are a useful case study.

What are automatisms and why are they used?

Antonio Conte sides are typically well-drilled; they’re fit, focussed, and have a high level of clarity surrounding how they’re going to play (albeit there’s little room for overly extravagant inspiration within the rigid framework). Within weeks of training a team, Conte will have instilled a number of key automatisms into his side; and these can raise the floor of a team very quickly.

So what do we mean by an automatism? An automatism is effectively a combination, usually a passing move, which is repeatable and requires little-to-no thought to execute because it has been drilled to the point of happening automatically within a certain game situation. These semi-automatic situational responses can also be applied to pressing, as was the case at Ralph Hasenhüttl’s Southampton.

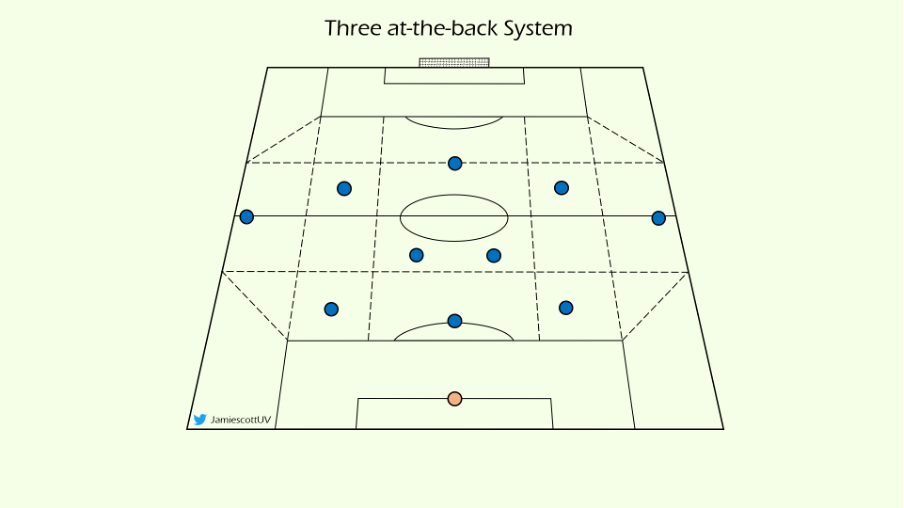

They can be used indiscriminately, or as more of an emergency option, for example when a side comes under dangerous pressure. Specific formations are certainly conducive to better use of automatisms, most notably three at-the-back systems, which are quite rigid in terms of player rotations, but occupy the zones of the pitch with relative balance.

Implementing a predetermined set of passing combinations in a system which is both easy to understand positionally, and has ideal natural angles, is often a winning battle. Conte usually favours a three at-the-back system – although this may be correlation with his predilection to coach automatisms, rather than pure causation.

As touched upon earlier, automatisms are a great method of ‘floor raising’ for a team, bringing the lower bound of a team’s performance level up to a certain benchmark. With hardworking players who are open to strict tactical plans, automatisms can be quick and easy to implement. Antonio Conte has had success in his first seasons at both Chelsea, where he won the league title, and Spurs, where he revived a poor start under his predecessor Nuno, to beat Arsenal and United to a top four spot come May. At Chelsea, Conte’s side went 13 wins on the trot immediately after reverting to a three at-the-back system. Within weeks of taking over at Spurs, the tactical hallmarks of a Conte side were very evident, and Spurs were playing in more of a metronomic fashion.

Specificities of Conte’s automatisms

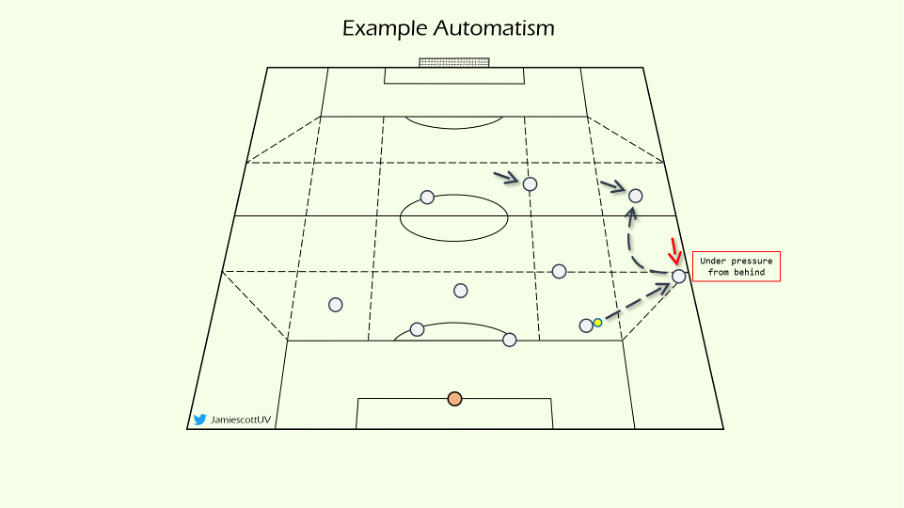

Examples of specific combinations are important when articulating why automatisms are useful in certain circumstances. One of Conte’s prime automatisms is the wall pass out of danger from the wingback (when they’re deep and wide in build-up).

Typically, when a Conte side is pressed man-to-man, ball possession in the back three attracts pressure. The wingbacks will drop to offer support from the wide zone, but wingbacks are easy to mark in a touch-tight manner. They can’t writhe put of pressure by turning out: the side-line is forcing them to play back or inside (both options are playing into pressing traps). The automatism, however, instructs the wingback to orientate themselves in a way to protect the ball from pressure, but in an angle to play the ‘round the corner’ pass up field (this pass is usually chipped or aerial so as to avoid being intercepted). This pass is often blind, completely premeditated. The beauty of the automatism, however, is that the winger and striker will both know what is coming – the team have trained this combination to death. Their movements into the zones where the aerial pass could land is triggered by the ball coming into the wingback, under the specific pressure the team is under. They’re two steps ahead of the game, thanks to the knowledge of the automatism. This understanding and pre-emptive play turns a speculative get-out-of-jail ball into a progressive pass, with a higher success ratio. This automatism grants a means of escaping pressure, and a means counter-attacking a strong press.

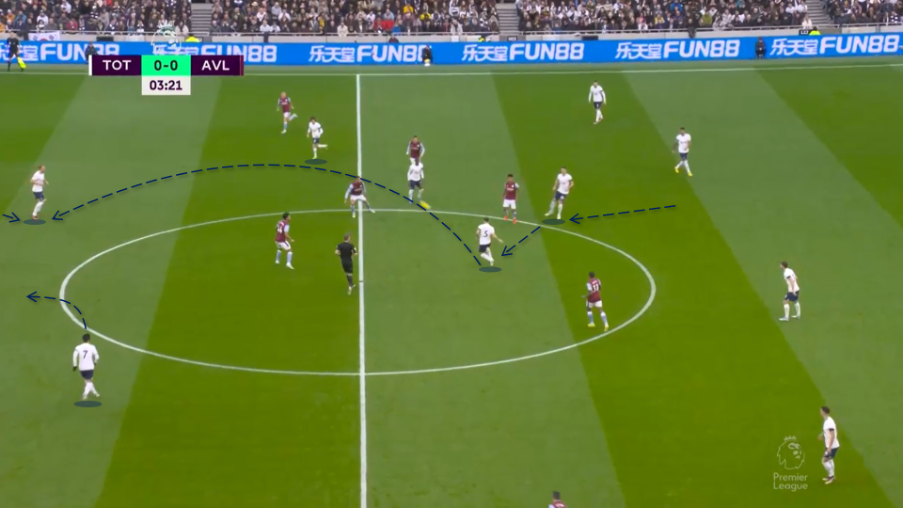

In a similar fashion, Conte’s sides like to utilise the premeditated (or blind, depending on your perspective) ‘round the corner’ pass in other areas of the pitch. In the example below, Højbjerg receives from his centreback in an attacking transition, and blindly plays forwards for Kane. Kane has been instructed to drop deeper in anticipation of this, and Son is triggered to look in behind as soon as he sees Kane dropping. Kane dropping to receive back-to-goal also triggers other players to move into his eyeline to receive a safer wall-pass, as an option for Kane if he decides not to wrestle with his defender and play a ball in-behind.

The instance above is also a prudent example of how automatisms have utility in transitions, for a number of reasons. Firstly, your team can play from back to front quickly, because time isn’t taken to make expansive decisions on the ball: much of the play is instantaneous and predetermined. This speed of play and directness allows the team in possession to maximise on the disorganisation of the team who lost possession. Furthermore, the direct nature of an automatism allows the team in attacking transition to have a good chance of beating the counter-press, such is the typical efficacy of an automatism versus (disorganised) pressure.

The balanced outlook on automatisms

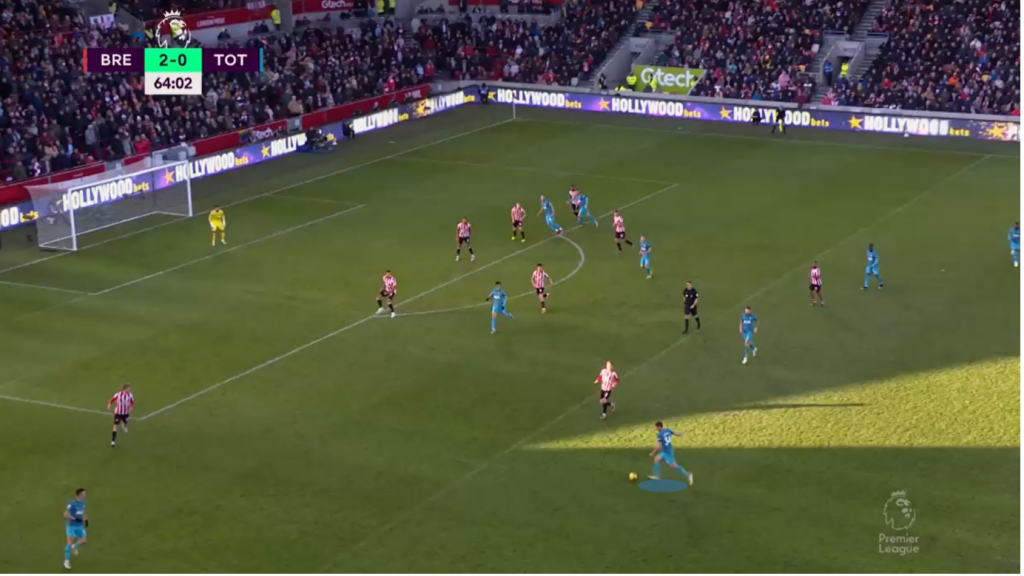

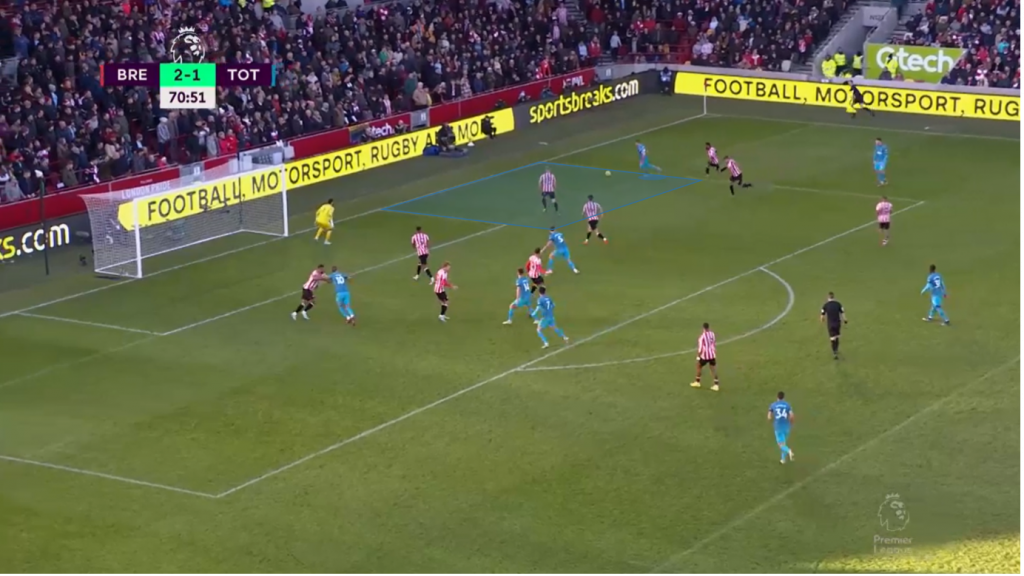

Playing in an automatism-heavy system can also introduce a number of unique problems to a team, however. Antonio Conte’s Spurs endured struggles away at Brentford in December 2022, in a game where the limitations of the system were clear to see.

Spurs struggled to keep possession, as a result of their proclivity to play direct premeditated passes upon winning ball possession. Brentford are a side who are strong in duels and fighting for second balls and dragged Spurs into a scrappy match where there were many transition scenarios. Spurs struggled to retain possession on many occasions after winning the ball back, after repeatedly firing loose balls into the front line.

Brentford’s approach was also largely successful against Spurs in the first half too and the reasons for this unearth some interesting, and significant issues with Spurs’ automatism-heavy play. Opposition analysis is something virtually every team in professional football does and predicting how an opponent will play can be easier if they have obvious, repeated patterns of play. It is simply the nature of automatisms to be easy to identify; if the uptake of the tactics by the players is quick because learning automatisms doesn’t require much inspiration or free-thought, they can also be easy to set up against. Easy in the sense that your team will know what’s coming, anyway; whether your side can stop them is another matter.

Brentford highlighted exactly how to tackle a side whose system is predictable and in doing so also halted Spurs. Brentford pressed well, forced Spurs to play into traps, screened lanes which Spurs like to play through, and directed play into areas where Spurs were at a disadvantage. While Spurs’ 3-2-5 system fought back, it was because they slowed play down and established more control more than anything. Lenglet being the spare man at the back allowed Spurs to progress through him in the half-space and he assisted Harry Kane for a goal and a headed effort against the bar, both directly stemming from half-space carries and crosses.

Furthermore, Dejan Kulusevski drifting into the wide space instead of remaining in the half-space also created danger for Brentford; this sort of ingenuity can be so important when breaking a defensive block.

The movement of Dejan Kulusevski has been analysed on this site before, and in the context of a holistic discussion on automatisms, it brings up another pertinent point: automatisms can often rely on individual brilliance in the final third, as creativity is often limited. This brilliance often falls under either high-class execution (for example winning an advantageous 1v1 duel or high-quality shooting, passing or crossing execution), or, in the form of individual inspiration. The latter can almost be seen as a player defecting from the system to play their own way, as breaking the mould of the system with free-thought and unpredictable brilliance. Dejan Kulusevski’s proclivity to move into the wide space to receive and create threat certainly highlights this. Eden Hazard was subbed early in his first game under Antonio Conte at Chelsea, but Conte seemed to accept that Hazard’s mercurial brilliance was a ‘necessary evil’, and the Belgian repaid the faith with a stellar season, as he was named in the PFA Team of the Season. Individual inspiration can be necessary, even for an automatism-heavy side.

On the topic of individuals, playing with automatisms does offer an immense degree of role clarity to players. From small things, such as body-orientation when receiving and micro-movements to dis-mark and find space, to more macroscopic aspects like combination play (which can encompass wall-passing, etc), the players are handed a toolkit of skills which they can fall back upon. While in some players this can limit them in the long-term, in others it refines their game, making them ruthlessly efficient in certain roles. Some players flourish, some are reduced down to a shadow of their abilities. This is reflected in Antonio Conte’s transfer strategies, which prioritise system players irrespective of age or resale value.

Conclusion

The question of whether automatisms are going out of fashion is interesting, because the answer actually widens the scope of the initial question. Reliance on a strict tactical system at the top level seems to be decreasing to an extent and this implicates examples such as (but not limited to) man-to-man pressing systems, highly-disciplined positional play and possession systems, and automatism-heavy systems. With greater emphasis on dynamism, adaptability and problem-solving within an overarching framework becoming more and more common to see, the time for a micromanaged system may be over at the very top. It is no longer a unique advantage to deploy a JDP system for example, nor is it when deploying a system solely limited to (thus dependant on) preconceived combinations. While there will always be a time and a place for high-discipline systems, particularly in raising the tactical floor of a team, greater flexibility to deal with high-quality opponents week-in week-out is becoming necessary. The tactical landscape seems to progress in a cyclical manner, and in the future, there may well be a time when high-discipline systems become so unconventional that their uniqueness can make them world-beating for a period. Alas, at present, this isn’t the case, and automatism-heavy systems are the king of high-discipline systems, built more for quick improvements and extracting value from high quality players than for league domination.

Header image copyright IMAGO/COLORSPORT/Ashley Western