Analytics FC Head of Content Alex Stewart revisists the concept of team styles across the biggest five leagues in Europe and analyses some fascinating changes

Europe’s top five leagues, the Premier League, Serie A, LaLiga, the Bundesliga, and Ligue 1, are on hiatus, although many players have headed to Germany to particpate in the UEFA European Championship. The end of the season is a good time to take stock and assess trends and so we have decided to revisit an article we did in 2022, and look at which of Europe’s top five leagues is the most tactically diverse.

Using Analytics FC’s coaching heat maps, developed as part of our Coach ID service, we can look at coaches in the top five leagues for the season just finished, and compare them tactically. It won’t tell us which league is the best, but it will show diversity of styles and approaches, which leagues are the most alike and least, and also how things have changed since we last looked.

To do this, we can use Analytics FC’s visual taxonomy of coaching styles:

Park the bus: this style focuses on setting up to defend deep out of possession and using counter-attacks as the main means of generating chances.

Direct domination: a style of play characterised by high pressing out of possession and a similarly direct approach when in possession.

Bait the press: this style sees a low block defensively, while in possession some short passing occurs deep, but with the intention of encouraging the opponent to press and then attack with more direct passing either in behind or towards a target man

Wing overload: the emphasis in this style is on combination play in wide areas and a reliance on wing-play, crosses, and cutbacks to generate chances

Deep build-up: this style is built on lots of short passes and a high volume of passing in possession, while there is an emphasis on pressing high out of possession

Full control: another high pressing style, but one that combines high pass circulation numbers and the ability to pin opponents deep in their half

Few teams are distinctly one of these styles; most show elements of several, which is why we use a map. We have also added a heat-map layer, which will show groupings, just as they would for a player’s actions on a pitch.

When interpreting these coaching style maps, keep in mind that generally, the X axis indicates an out-of-possession approach and the Y axis an in-possession approach. The teams on the left sit deep and defend more passively; the ones on the right have vigorous pressing, high rest defence, and often (though not always) counter-press aggressively. Likewise, in possession, the teams towards the bottom keep the ball with lots of short passing, and the ones at the top are vertical and direct (this doesn’t necessarily mean ‘long balls’, but could indicate speed of attack as well). So, a team sitting bottom right keeps the ball very effectively across the pitch, while also pressing high (the favoured style of elite coaches and teams), while top left sits deep and goes long.

It’s also worth noting that the X axis position is a good proxy for team strength, and you’ll tend to find the best teams further to the right, whereas the Y position is often a strong indicator of the coach’s individual tendencies (weaker, or less wealthy, teams who are towards the right are likely overperforming relative to budget). This means that a ‘bait the press’ coach will likely move towards being a ‘deep build-up’ or ‘full control’ coach as their team quality improves, or, in some instances, with time spent at the club (as they get their ideas across better) but a ‘bait the press’ coach will very rarely move towards being a ‘park the bus’ coach.

The data are generated by tenure and, in order to have sufficient sample size, we have used February 2024 as the general cut-off point. Interestingly, very few teams changed coach hugely before then (although some did: we see you, Napoli), and anyway, most teams who change manager mid-season don’t see an enormous tactical variation, not least because our cut-off is after the winter transfer window. One thing we have done different from the first piece is highlight coaches who have left or are leaving in red. We have not distinguished relegated teams in this way – just managers who have been let go or are retiring at the end of the season, of which there are quite a few.

When we last looked at this in 2022, using data from the 2021/22 season, Europe’s ‘big five’ showed a significant degree of difference. You can read the full piece here, but in short, Serie A was the most diverse, with a fairly high number of ‘direct domination’ and ‘full control’ coaches, and a surprising number of teams who sit in the ‘deep build-up’/’bait the press’ intersection. Ligue 1 had high numbers of ‘park the bus’ and ‘full control’ coaches, so two opposing ends of the spectrum, while the Bundesliga was susprisingly defensive, LaLiga surprsingly direct, and the Premier League was largely as expected, “with a clear middle ground of mixed ability, mixed style teams who have a blend of quality and pragmatism.”

So, let’s see what’s changed.

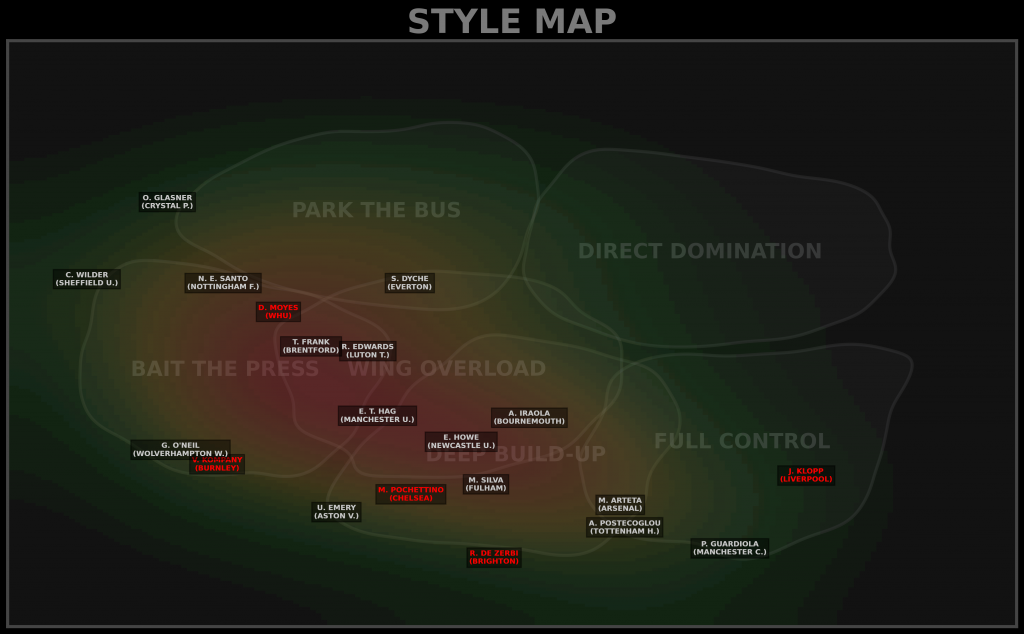

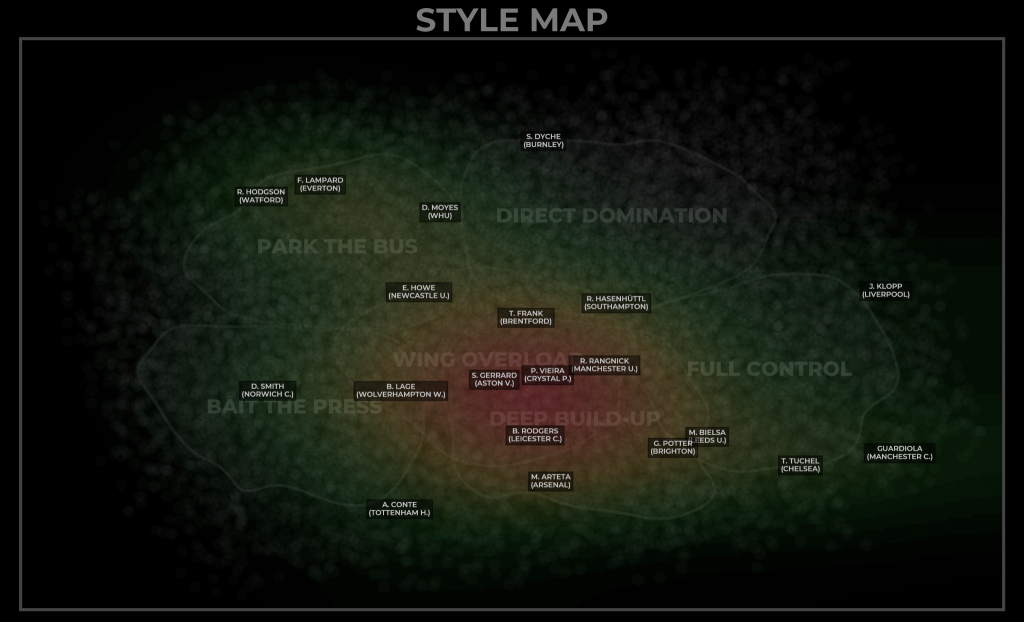

The Premier League

The first and clearest thing to note is the absence of ‘direct domination’ coaches, those whose style involves a very high proportion of direct, vertical passes, high pressing, and aggressive counterpressing, as well as more extreme ‘park the bus’ coaches (low block but with long ball or vertical in-possession). In 2021/22 there were still very few of these: Jürgen Klopp was on the intersection of ‘full control’ and ‘direct domination’, while Sean Dyche was at the top of the map, and Frank Lampard, David Moyes, and Roy Hodgson were all fairly extreme ‘park the bus’ coaches. Crystal Palace’s Oliver Glasner, who will likely shift towards the right of the map with more time to implement his ideas, is the most direct in-possession coach, but Dyche has increased his focus on possession somewhat, while the general trend is towards more teams who see more of the ball. In 2021/22 there were eight coaches who sat in the ‘park the bus’ or ‘direct domination’ zones, or within an overlap area between them are ‘wing overload’; this season, that is down to two, while Chris Wilder and Nuno are close.

Picking out a few specific coaches who are in both periods: Mikel Arteta’s transformation of Arsenal into a more dominant, ‘full control’ approach is clear, while Thomas Frank’s Brentford has become slightly more defensive. Klopp’s Liverpool became more possession-focussed and less direct, as did Eddie Howe’s Newcastle, albeit starting from a more defensive base.

Interestingly, you can also see how some teams (we could even say clubs) don’t change much even with managerial changes. Ange Postecoglu has kept the possession-focus at Spurs but made them much less reactive and defensively focussed, but Everton are still in the same zone, even though they are less direct and defensive and Wolves are slightly deeper under O’Neill than they were under Lage but, again, pretty similar. Burnley certainly changed the most, with Dyche’s very direct style morophing into Kompany’s keep-ball, sit-deep style. Unai Emery has also instilled much more ball retention at Villa, with excellent results.

The Premier League in 2023/24 is still largely clustered around the ‘wing overload’/’deep build-up’ intersection, but with more ‘bait the press’ teams: in short, there is still a pragmatic general core, but more of the more defensive teams are trying to keep the ball in deep build-up and fewer are being direct in possession. All three relegated sides played a ‘bait the press’ style although Rob Edwards tried to bring more wing play and a slightly higher line to his side (indeed, if you compare his Championship tenure at Luton, it’s the same approach but more defensive in the EPL, which makes a lot of sense, even though it didn’t work out).

Again, generally weaker teams are on the left and stronger ones on the right but if we are giving flowers for approaching an elite style with ‘weaker’ (or less wealthy) sides, Andoni Iraola’s work at Bournemouth and Marco Silva’s Fulham tenure both deserve real credit. Meanwhile, it could be said that if ‘full control’ is generally the goal of any elite side, Manchester United under ten Hag still have some way to go, while Mauricio Pochettino did not manage to implement at Chelsea.

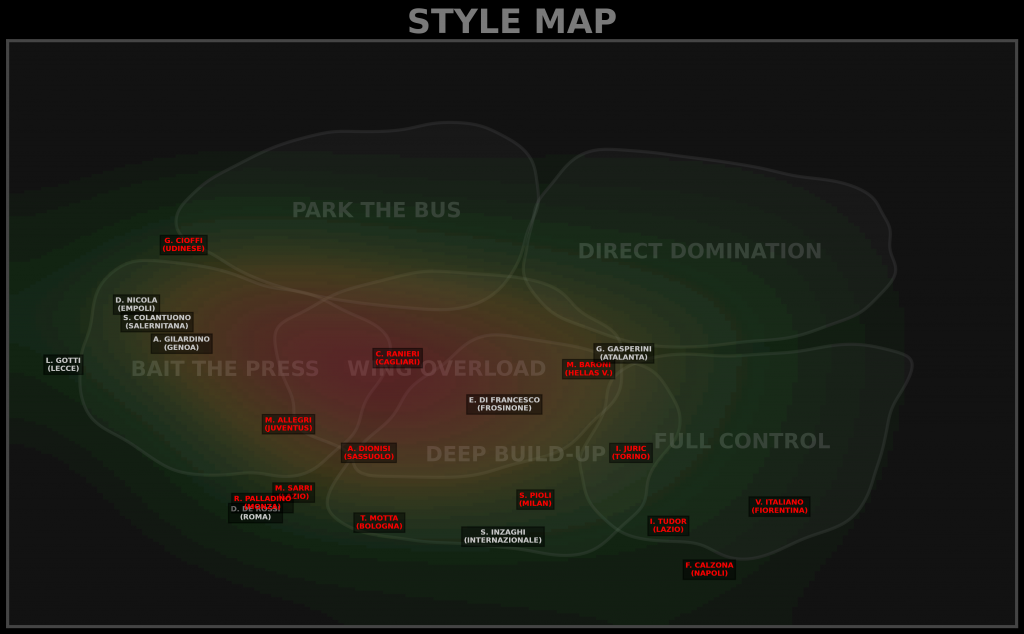

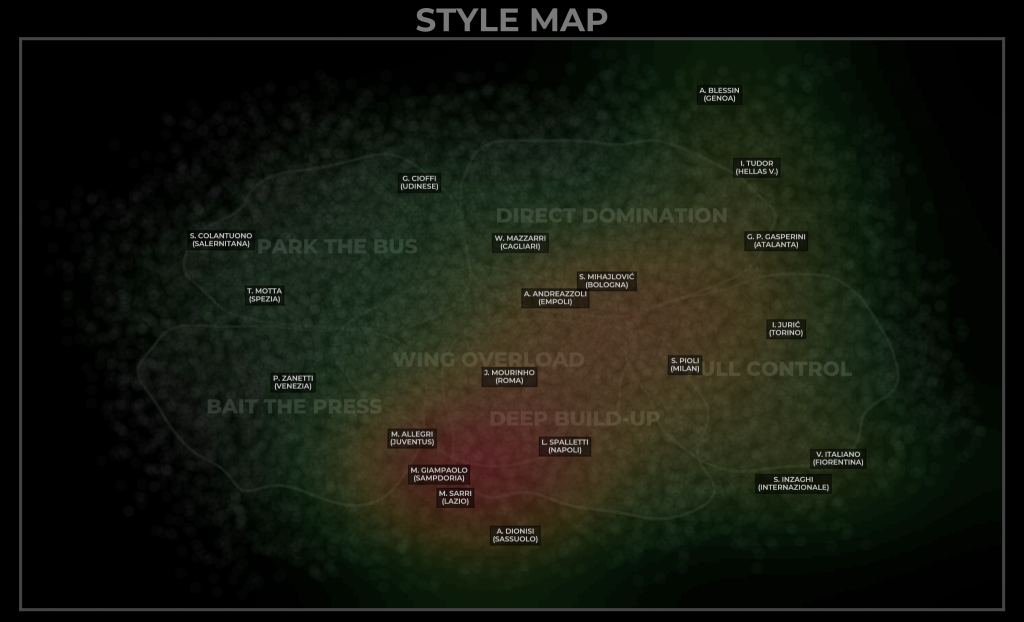

Serie A

Europe’s next strongest league, by national coefficient, is Italy’s Serie A. The first thing to note is the sea of red: Italy is not a stable environment for coaches. There’s a lot of movement between clubs, and this was generated before the widely reported move of Eusebio Di Francesco to either Venezia or Empoli, where Davide Nicola performed his usual relegation-avoiding miracle but may be off somewhere else (both are shown in white, though, as these are not confirmed). We have also included two Lazio coaches, Mauricio Sarri, who left in March, and Igor Tudor, who managed 11 games before leaving in June. This is interesting because it shows how Tudor was able to instil a far more aggressive out-of-possession style (moving Lazio to the right of the map), while having a very similar in-possession approach in terms of ball retention, volume and duration of passes, and so on (Lazio are almost exactly the same position vertically on the map under the two coaches).

There are a few really interesting things to note. Serie A was the most tactically diverse league in 2021/22 – now, it looks almost the same as the Premier League. Gone are all the direct ‘domination coaches’, and Tudor altered his approach to an unusual degree between his Hellas Verona tenure in 2021/22 to his short Lazio stint this season. Gian Piero Gasperini’s Atalanta has a similar in-possession style but is defending in a less extreme manner, and the same can be said for Ivan Juric and Gabriele Cioffi, albeit on the opposite side of the map in Udinese’s case. Indeed, less extreme defending is a general trend, with even Simeone Inzaghi’s superb Inter side moving to the left on the map. It’s worth picking out Genoa: they went down at the end of 2021/22 under the wildly direct Alexander Blessin, but have achieved mid-table security in their first season back in the top flight with a far more patient, deeper approach, indicating how the stylistic shift under Alberto Gilardino (a former Genoa player) has been very effectively managed and supported with good recruitment.

What is helpful is that we can also prove that these changes are in coach and team style, not in the way the data is being used (if you were worried): look at Vincenzo Italiano at Fiorentina or Max Allegri at Juventus (both of whom have left their jobs; Italiano will continue Motta’s amazing work at Bologna in a brilliant hire by the Rossoblù, while Allegri is being replaced by the former Bologna boss). Both coaches have barely shifted between 2021/22 and 2023/24 (let us also recognise here that Italiano was coaching an elite style of football with the 8th highest squad total market value according to Transfermarkt, which is really impressive).

But around them, Serie A’s tactical landscape has rocked. Eight coaches sit in or just below the ‘bait the press’ zone, with a further two (Ranieri and Cioffi) almost there, compared to only two in 2021/22. Six coaches sat at the extreme right of the map in 2021/22; this season, it is one.

Italian football has shifted to the kind of patient, possession-focussed approach it’s usually characterised as having, again largely following the same quality gradient as the EPL (weaker teams left, stronger ones right). This poses two questions, one of which we can answer as we progress with this piece, and one we cannot without additional analysis: is elite football generally becoming more possession-focussed and less direct and defensively aggressive, and was Serie A in 2021/22 an outlier, for Italian football as much as generally? We might return to the second question in another piece, but we can certainly continue to pick out general trends as we move on to the other leagues this season.

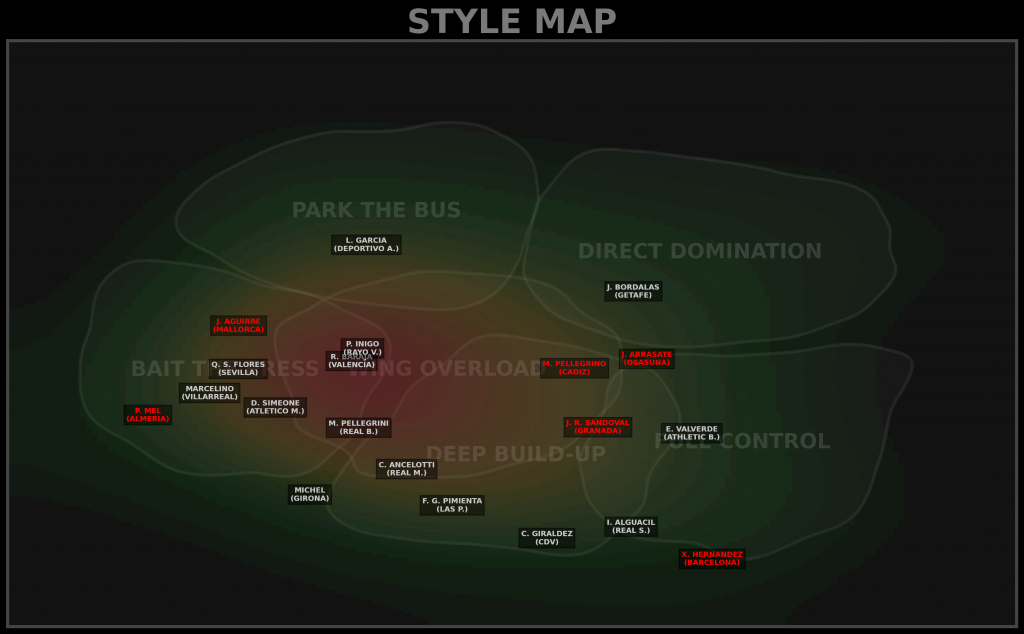

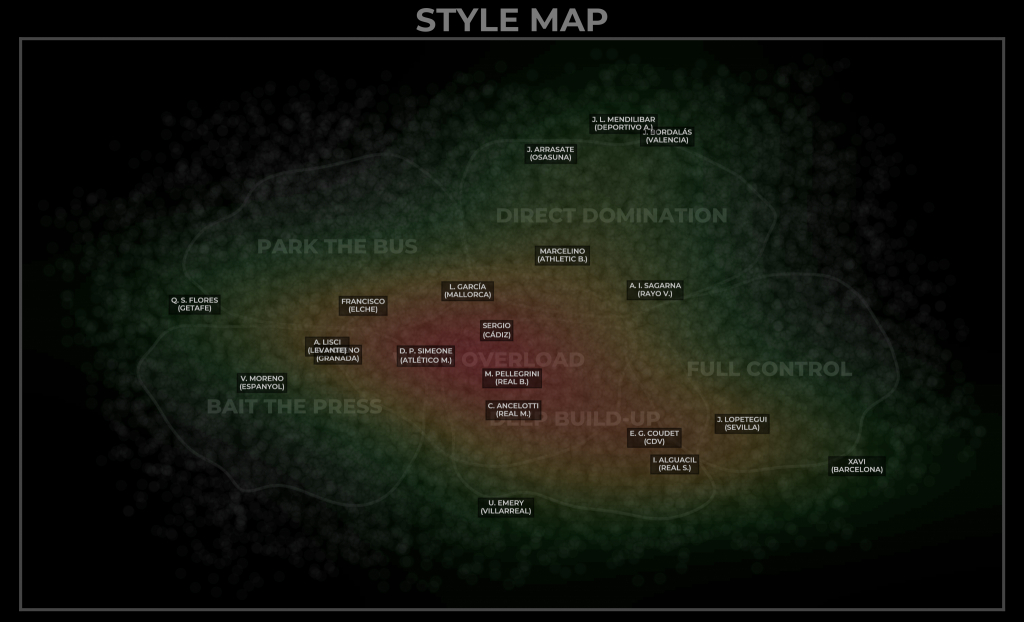

LaLiga

In 2021/22, we described LaLiga as “a bit odd”, largely because “La Liga [had] more ‘direct domination’ teams than the Premier League or the Bundesliga, which is probably at odds with the perception of high possession, slow build-up football associated with Spanish football”. Well, that is no longer the case, although the high priest of direct football in Spain, José Bordalás, is back at Getafe and playing that style, albeit a less extreme version than his Valencia side were conjuring in 2021/22.

Indeed, the two most direct teams, Bordalás’ Getafe and Jagoba Arrasate’s Osasuna, finished 12th and 11th respectively, despite being 14th and 15th in Transfermarkt’s total market value list for LaLiga, showing that perhaps (in Spain at least), playing direct and vertical is a way of overachieiving relative to budget (something we will look at in more detail in future). Indeed, Arraste has done a marvellous job at Osasuna, punching above their financial weight and achieving a decent impact on the team’s underlying numbers; he will be at the helm of Mallorca next season.

But, in general, we can see exactly the same trend as in the two leagues previously considered: more teams focussing on low blocks in defence and keeping the ball in possession, with a commensurate decline in teams playing vertically in possession and aggressively out of possession. Ruben Baraja’s Valencia exemplify this: under Bordalás they were the second most extreme ‘direct domination’ side in the top five league in 2021/22 (after Blessin’s Genoa); they now sit in the ‘wing overload’/’bait the press’ intersection zone, a huge shift over the course of two seasons.

In total, the number of ‘direct domination’ sides has dropped from five to one, while the number of ‘bait the press’ teams has increased from three (or five if you count those just outside or on the line) to eight. It is also interesting to note there are no pure ‘wing overload’ teams, with most central sides employing some width but subordinate to another style, another big shift from 2021/22 when there were four or five teams who could be realistically described this way.

As with Serie A, a few coaches have barely altered their style at all. Diego Simeone’s Atleti continue to be surprisingly defensive for a big side, while Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid and Manuel Pellegrini’s Real Betis occupy much the same spot on the map as they did in 2021/22. Quique Sanchez Flores has moved from a very defensive style at Getafe to a slightly less defensive one at Sevilla, but with an almost indentical approach in possession. Meanwhile, Rayo Vallecano have gone the other way: under Iñigo Pérez they sit much futher to the left, but at almost exactly the same vertical position, as they did under Iraola (note too how Iraola at Bournemouth is largely a slightly more defensive, slightly less direct version of his Rayo tenure, showing the consistency that most coaches have across tenures). And Imanol Alguacil continues to impress at Real Sociedad.

Let’s also check in on a prediction from the 2021/22 piece: “Athletic Club finished eighth under the consistently excellent Marcelino but he has departed; they have recruited Ernesto Valverde, a two-times La Liga winner with Barcelona who should nudge them further towards the full control style, at odds with how Athletic usually play.”

Yes, we got that one right, and didn’t it work out well for them?

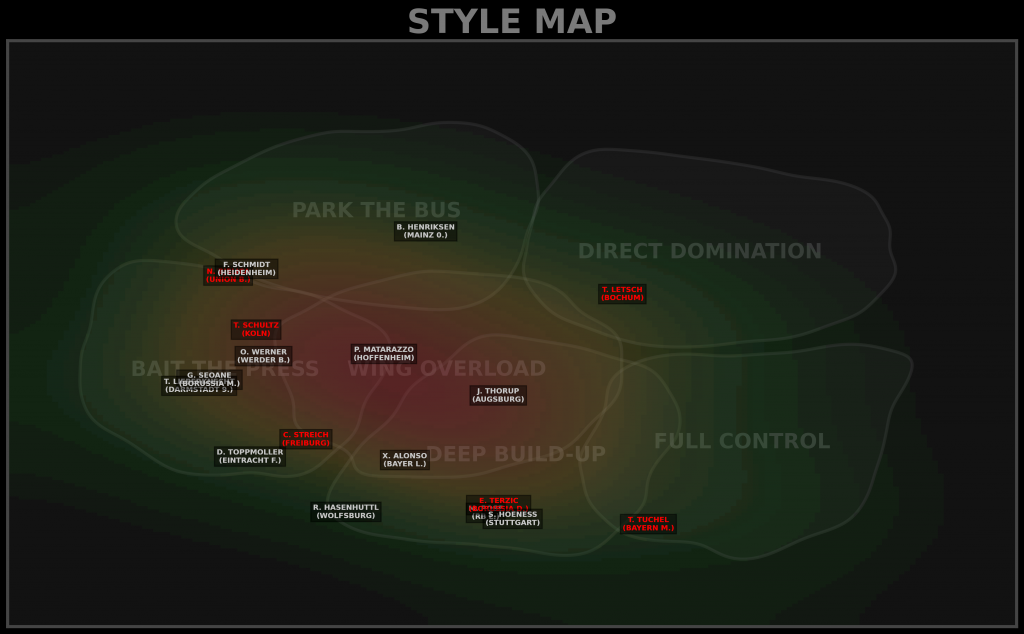

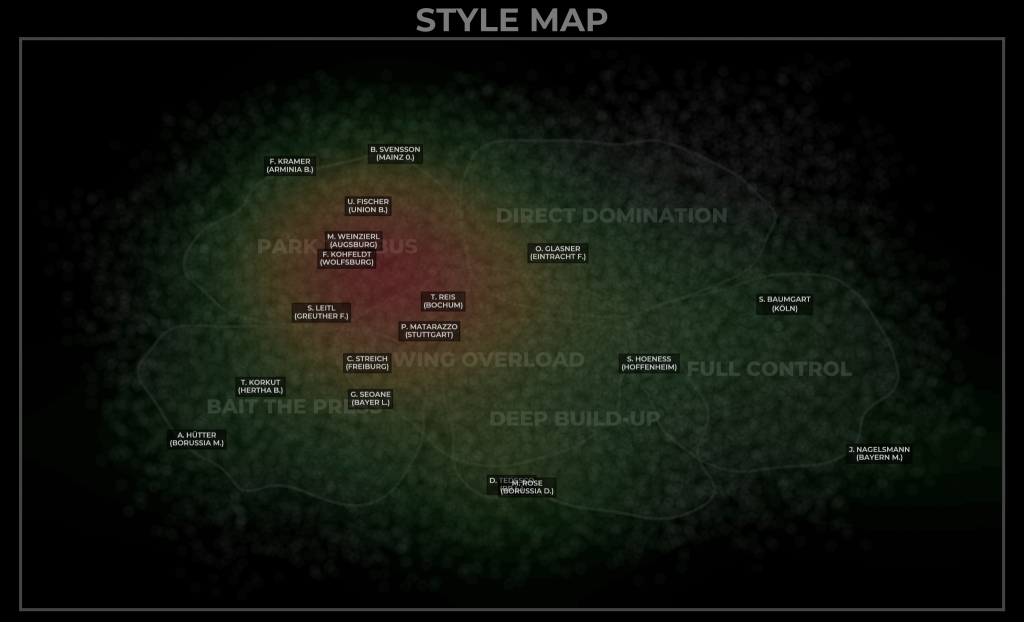

The Bundesliga

We were surprised when looking at the 2021/22 data, writing at the time that “the Bundesliga’s reputation as a very high pressing league take a hit with only one team, Oliver Glasner’s Eintracht Frankfurt, a ‘direct domination’ team…and with a significant cluster in the ‘park the bus’ sector, the Bundesliga is generally much more defensive and less aggressive and direct than one might expect”. Glasner is, of course, now a ‘park the bus’ coach at Palace but, as stated above, we would expect him to move right on the map, more towards the position he occupied at Frankfurt.

Indeed, the Bundesliga has not changed much, and also clearly has a way of getting coaches adhering to this more defensive style shift: just look at Ralph Hasenhuttl, an RB disciple who played a ‘direct domination’/’wing overload’ style at Southampton in 2021/22 and who now sits on the corner of the ‘deep build-up’ section, a rare coach who has significantly altered his out-of-possesion appraoch (let’s see if he shifts somewhat as he his tenure develops).

It feels like the Bundeliga has actually changed less than the three leagues we have looked at so far: there are fewer ‘park the bus’ coaches but they have moved down to be more ‘bait the press’, the in-possession alternative with the same out-of-possession defensive focus and low line. For Glasner in 2021/22, see Letsch in 2023/24, although he left Bochum with five games to play and they narrowly escaped relegation by winning the play-off on penalties. And Bo Henriksen’s Mainz is the only real other outlier, but his ‘park the bus’ style could hardly be considered an extreme example of that approach. Look, too, at Mainz under Bo Svensson in 2021/22: they are almost identical. This is almost certainly an exmaple of good internal processes around identifying similar coaches to bring in to coalesce around a ‘club style’ or playing philosophy.

The main shift has been that there are no longer extreme possession and pressing coaches in the elite Guardiola / Xavi / Italiano / Nagelsmann style. Thomas Tuchel was the closest, while Sebastian Hoeneß’ Stuttgart is less defensively aggressive but more possession-focussed than his Hoffenheim side was in 2021/22. There are also more ‘deep build-up’ caches than before, a kind of middle ground for teams who want to play possession-based football but lack the dominance to be ‘full control’, or the need to be as defensive as ‘bait the press’.

The league has clearly coalesced somewhat around a more defensive, possession-based approach, but without the wild outliers in 2021/22 that LaLiga or Serie A had, this following of the general trend in elite football feels like less of a shift anyway. The Bundesliga reads like a Premier League but compressed towards the low block side of the map (left), which could make it an interesting hunting ground for mid-to-lower level EPL clubs.

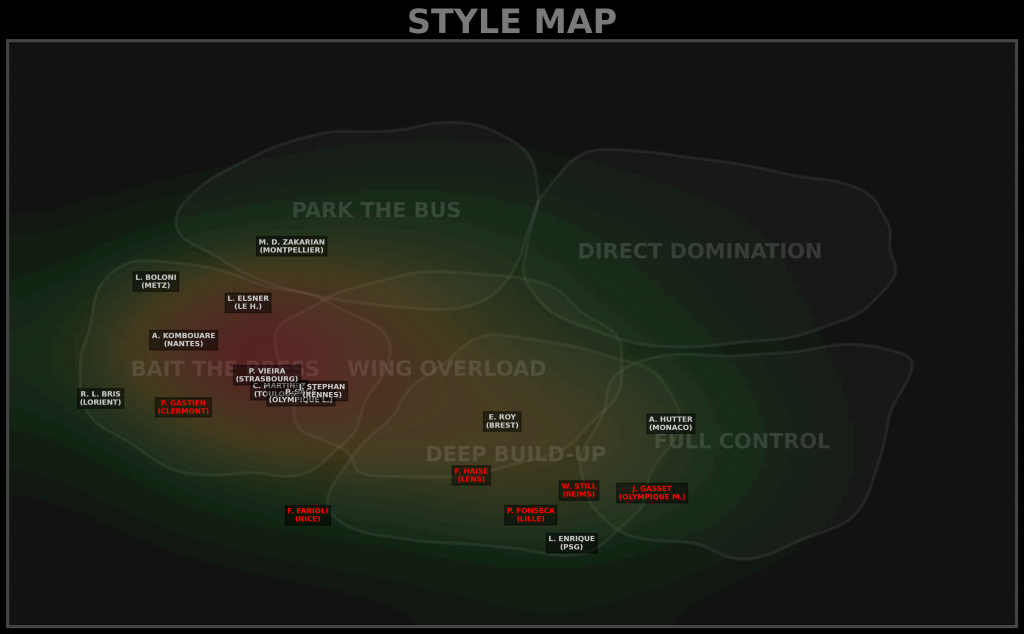

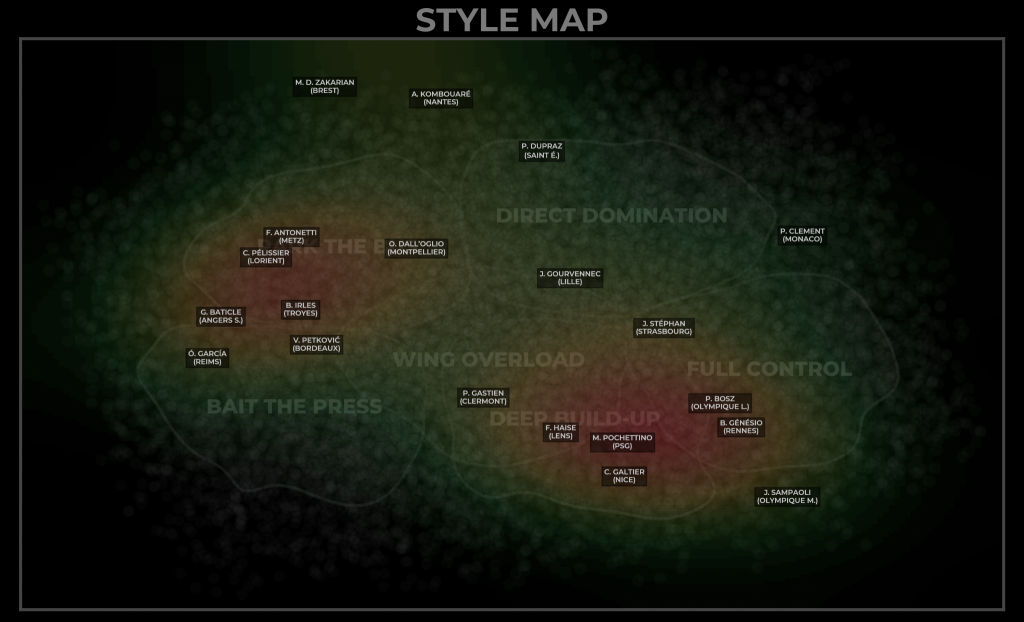

Ligue 1

Ligue 1 was a very interesting tactical mix in 2021/22, with no true ‘bait the press’ sides, a few very direct but defensive sides (Nantes, Brest, AS Saint-Étienne), and two clear clusters around ‘park the bus’ and the ‘deep build-up’ / ‘full control’ interscetion. This is perhaps because there is a more distinct wealth gap: again using Transfermarkt’s total market value, there are eight clubs with suqads valued at more than €190m, and 10 at less than €130m (with five under €100m). Serie A, for example, has a much more gentle gradiant from highest to lowest value. It’s worth noting that Brest and Reims both sit with the ‘rich’ group, testament to quality coaching from Éric Roy and Will Still. Lyon, Rennes, and Nice, by contrast, play a more defensive style of football than one might expect from clubs with relatively higher levels of resource.

While Ligue 1 was the most interesting league in 2021/22, it has undergone relatively little change. Strip out the four more vertical coaches (Michel Der Zakarian, now the most direct coach in the league but at Montpellier, Antoine Kombouaré, back at Nantes but more possession-focussed, Pascal Dupraz, and Paul Clement) and you have a very similar map. Those teams have moved: ASSE to Ligue 2, Monaco to a more ‘full control’ style under Adi Hütter, Brest to a more ‘deep build-up’ style under Roy, and Nantes towards a more possession-based but still defensive approach, back under Kombouaré.

Again you can see the consistency of coaches like Franck Haise at Lens, who will be at Nice next season. It’s also interesting to note that Metz under László Bölöni in 2023/24 looked an awful lot like Metz in 2021/22 under Frédéric Antonetti: they finished 19th in that season, and 16th this, going down after losing the relegation play-off to ASSE. But consistency in tactical style is generally a good thing, especially for a club like Metz who will always be up against it in Ligue 1 for financial reasons: it allows for squad planning continuity and helps in recruitment, which can always be tricky for yo-yo clubs.

But in general, it’s like the two clusters have tightened, drawing in teams towards the two stylistic gravtional centres, attracted perhaps by familiarity, prevailing tactical wisdom, or the general trend in football to focus more on possession.

Conclusion

Europe’s top five leagues should exemplify the best in football: they largely have the best players, the best coaches, and the most money. Any tactical trends that are present in these leagues sholuld therefore be regarded with real interest as a reflection of tactical thinking at the top end of the game. Of course, interesting tactical and stylistic things occur elsewhere, but this is perhaps because the stakes are highest in Europe’s top five leagues, leaving little room for experimentation or the imposition of ideas considered challenging or difficult to implement.

It is clear that, across elite European football, there has been a shift towards possession and away from verticality across teams of all shapes and sizes. In addition, the leagues who were already most like this, the Bundesliga and Ligue 1, are the ones who have shifted least. Stylistic extremes are less common, too, whether it is the ultra-possession-based, high pressing football of the ‘full control’ style or the sit deep, chuck it long approach of ‘park the bus’: teams are starting to look more like each other in their styles, even as there are still tactical subtleties that distinguish them.

The reasons for this are many, probably, not least that tactics and style tend to move in prevailing currents, picked up and done first by the best teams or the most progressive managers, before proliferating down through the pyramid. But it’s also probably true that the growth of ‘bait the press’ teams is a reaction to the increasing financial inequality of football even within the richest leagues. The better teams have grown richer, and therefore can attract better players; the less well-off sides need to react and have done so by becoming more conservative in their style. In addition, the improvement in pressing schemes, as teams get better out-of-possession, has probably encouraged more teams to try to exploit that by drawing teams on, and then trying to go past them.

There are still outliers, direct counter-attacking teams who do so from a deep block and teams who favour high pressing out of possession and a similarly direct approach when in possession, but these are fewer and further between than even two seasons ago.

Will we see a shift back towards more direct approaches as a reaction to this, as teams seek to use difference to gain an advantage? Possibly, but an increasingly congested calendar and tighter squad spending rules (and registration ones in England) could make this unlikely (and are also probably a cause of a generally more patient approach, even as physicality overall increases).

Whatever happens, observing and analysing stylistic shifts among the top tier of European football will always have value, as the implenetation of tactical and stylistic approaches on the pitch can shed light on changes happening off it, as well.

Header image copyright IMAGO / Propaganda Photo / David Rawcliffe