Tactical diversity often makes for interesting match-ups. Alex Stewart and Piotr Wawrzynów look at coaching styles across Europe’s top leagues

What makes a league watchable? As football fans, we look for excitement and, perhaps, a degree of unpredictability. While some leagues seem to have assured winners going in to most seasons, a variety of styles and approaches can still make for a wide variety of match-ups, contrasting styles, and intriguing tactical battles. If everyone played the same, most matches would come down to which team had the better (more expensive) players; tactics are one way that a smaller side can best a more expensively assembled one and potentially upset the economic hegemony prevalent in football.

Every league wants to suggest that it’s the best, the most entertaining, and intriguing tactical battles are one way of selling that idea. Of course, it’s impossible to say what the best league actually is, but can we look at which leagues are most tactically interesting, or different?

Yes: using Analytics FC’s coaching heat maps, we can look at Europe’s top five leagues last season, and compare them tactically. It won’t tell us which league is the best, but it will show diversity of styles and approaches, and which leagues are the most alike and least among its constituent teams.

To do this, we are using Analytics FC’s visual taxonomy of coaching styles:

Park the bus: this style focuses on setting up to defend deep out of possession and using counter-attacks as the main means of generating chances.

Direct domination: a style of play characterised by high pressing out of possession and a similarly direct approach when in possession.

Bait the press: this style sees a low block defensively, while in possession some short passing occurs deep, but with the intention of encouraging the opponent to press and then attack with long balls either in behind or towards a target man

Wing overload: the emphasis in this style is on combination play in wide areas and a reliance on wing-play, crosses, and cutbacks to generate chances

Deep build-up: this style is built on lots of short passes and a high volume of passing in possession, while there is an emphasis on pressing high out of possession

Full control: another high pressing style, but one that combines high pass circulation numbers and the ability to pin opponents deep in their half

Few teams are distinctly one of these styles; most show elements of several, which is why we use a map. We have also added a heat-map layer, which will show groupings just as they would for a player’s actions on a pitch.

When interpreting these coaching style maps, there are a few things to bear in mind. The first is that the data are generated by tenure and, in order to have sufficient sample size, we have used February 2022 as the cut-off point: if there was a managerial change before February, we used the new coach; otherwise, it’s the previous coach. While this is not ideal, most teams who change manager mid-season don’t see an enormous tactical variation, not least because our cut-off is after the winter transfer window.

The second thing, which will help you read these charts, is that the X axis shows defensive style, while the Y axis shows attacking approaches. Defensively, the closer a team sits to the right, the more they press; the closer to the left, the deeper and more passively they defend. In terms of attack, the closer to the top, the more direct a team’s style; the closer to the bottom, the more horizontal, keep-ball possession.

It’s also worth noting that the X axis position is a good indicator of team strength, and you’ll tend to find the best teams further to the right, whereas the Y position is often a strong indicator of the coach’s individual tendencies. This means that a ‘bait the press’ coach will likely move towards being a ‘deep build-up’ or ‘full control’ coach as their team quality improves, but a ‘bait the press’ coach will very rarely move towards being a ‘park the bus’ coach.

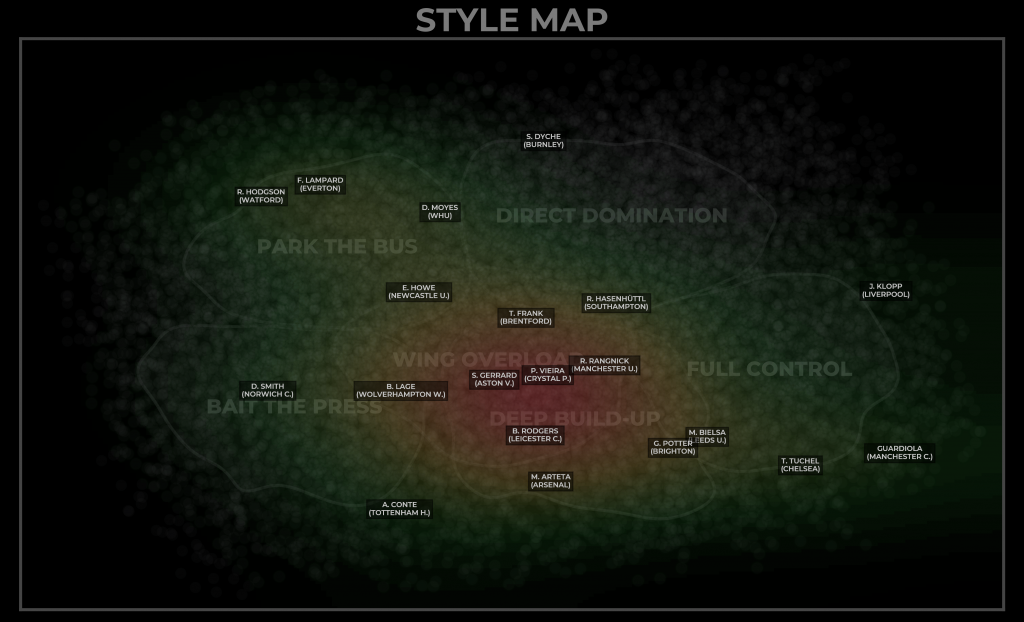

Let’s now look at each of Europe’s top five leagues, starting with the Premier League.

The Premier League

There are few surprises here: Pep Guardiola is a ‘full control’ coach, with Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea the nearest side in terms of style. Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool do use a ‘full control’ style, but are closer to a more direct style, which is due to the more direct passing style his side often employs. Marcelo Bielsa’s tenure at Leeds provides their entry, as Jesse Marsch only took over at the end of February. He and Graham Potter were remarkably similar in approach, sitting at the intersection between ‘full control’ and ‘deep build-up’, however different the results they achieved.

The Premier League also shows a clear cluster of teams in the ‘deep build-up/wing overload’ intersection, with four teams distinctly in that region; Arteta’s Arsenal uses less width and more deep build-up, while Lage’s Wolves strays more towards ‘baiting the press’ and Thomas Frank’s Brentford are also near, but more direct in their approach.

Generally, weaker teams are towards the left, with relegated Dean Smith’s Norwich and Roy Hodgson’s Watford furthest left, along with Frank Lampard’s Everton. But David Moyes’ West Ham are a significant outlier: a genuinely successful side on the intersection of the deep defence, counter-attacking style and occasional high pressing. Meanwhile, Sean Dyche’s Burnley played a more ‘direct domination’ style than one might expect, but also went down.

We can also expect a few things to happen: Conte’s Spurs will probably move in and up, getting better at exploiting wide areas with the signings of better wing backs like Ivan Perisic, while Everton should improve with the signings they have made and shift towards the right. The other teams worth keeping an eye on are Ralph Hasenhuttl’s Southampton, a direct domination side who have lacked quality but made some genuinely interesting, young signings which could change how the Austrian coach has them playing, and Eddie Howe’s Newcastle, who finished the season strongly under a coach who wants to play more of a deep build-up style; expect to see them move towards the centre of the heat map.

In general, the league has its outliers in terms of quality and identity, but there is a clear middle ground of mixed ability, mixed style teams who have a blend of quality and pragmatism.

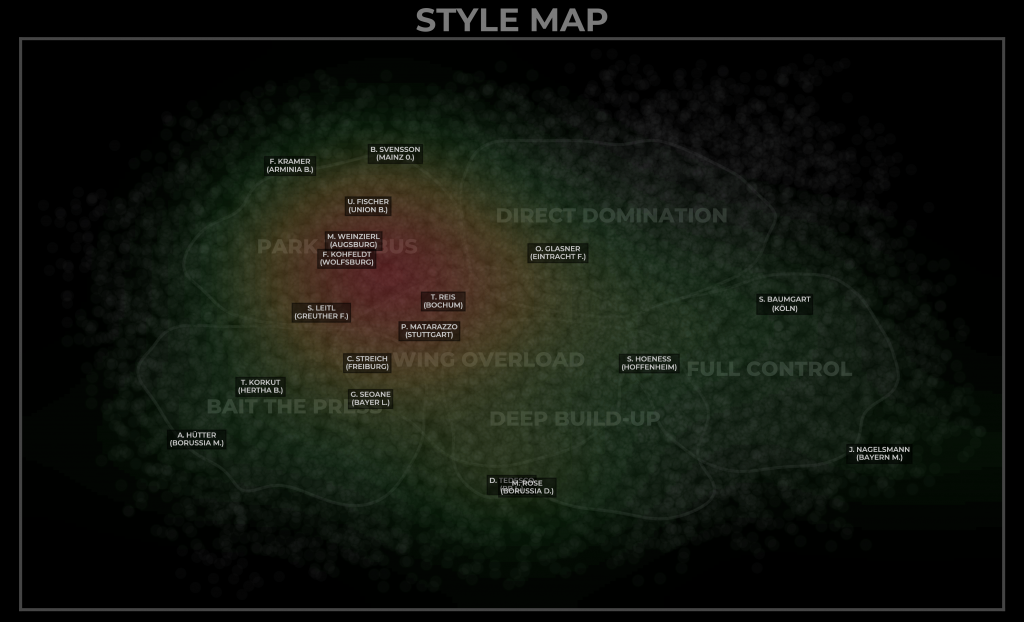

The Bundesliga

The Bundesliga throws up some major surprises. The biggest cluster of seven is in the ‘park the bus’ area, with Pellegrino Matarazzo’s Stuttgart intersecting that region with the ‘wing overload’ one. No team really plays the ‘wing overload’ style, though, one which is pretty common elsewhere, while the Bundesliga’s reputation as a very high pressing league take a hit with only one team, Oliver Glasner’s Eintracht Frankfurt, a ‘direct domination’ team.

There are stylistic similarities to Premier League sides: Marco Rose (Borussia Dortmund) and Domenico Tedesco (RB Leipzig) were very similar to Arteta’s Arsenal, while Julian Nagelsmann’s Bayern Munich occupy the same spot on the map as Guardiola’s City, exactly as one might expect.

What’s really interesting is that there are only five or six teams on the right-hand side of the map, including Steffen Baumgart’s FC Koln (who look like a slightly less successful Liverpool on the map and finished a very creditable seventh), and with a significant cluster in the ‘park the bus’ sector, the Bundesliga is generally much more defensive and less aggressive and direct than one might expect.

Its tactical diversity is less pronounced than the Premier League in terms of clusters, but also there is a significantly more pronounced difference between the more attacking teams and the more defensive.

The Bundesliga also went through a number of coaching changes during the season and after its close, so some of these teams will change position; it will be especially interesting to see where Borussia Monchengladbach and Borussia Dortmund end up next season under Daniel Farke and Edin Terzic, both former Dortmund II head coaches.

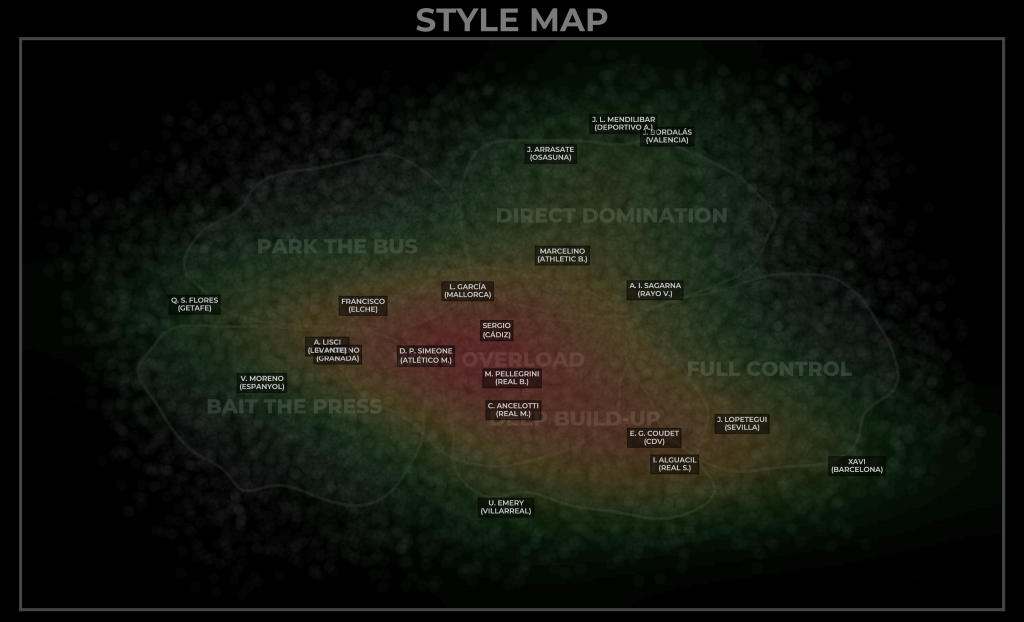

LaLiga

La Liga is also a bit odd. The primary cluster is like the Premier League’s, the intersection around ‘wing overload’ and other styles. Xavi’s Barcelona occupy the ‘really good team’ spot, while Unai Emery’s Villareal are amusingly close, stylistically, to Arteta’s Arsenal. But, otherwise there is some variety.

There are three teams who pressed high and played direct, Deportivo Alaves, Valencia, and Osasuna. The latter two finished 9th and 10th, but Alaves struggled enormously, were relegated with the lowest points total in the league; their manager, Joe Luis Mendilibar, was sacked in April. Player quality obviously makes a difference in how well teams can implement a style.

Quique Sanchez Flores’ Getafe, previously coached by Jose Bordalas, the king of low possession, direct football in Spain, seem to have stuck to a similar style of sitting off and counter-attacking at speed; Bordalas’ Valencia, by contrast, showed the stylistic evolution that a good coach working with better players can achieve by shifting right along the X axis from where his Getafe team would have been. It didn’t save him, though, as he was one of a significant number of managerial changes the end of the season, to go with a high number during it.

Another interesting position on the map is that of Celta de Vigo’s Eduardo Coudet, a self-avowed member of the Bielsa school of football; his spot on the heat map is almost exactly the same as Bielsa’s Leeds United.

La Liga has more ‘direct domination’ teams than the Premier League or the Bundesliga, which is probably at odds with the perception of high possession, slow build-up football associated with Spanish football. There are also no sides who are distinctly ‘park the bus’, the style where teams defend deep out of possession and use counter-attacks.

In fact, stylistically, you could say that La Liga is the Premier League but with the deep-sitting, countering attacking teams swapped out for teams who use high pressing out of possession and a similarly direct approach when in possession. In addition, two former Premier League managers, Carlo Ancelotti and Manuel Pellegrino, sit in that intersection of ‘wing overloads’ and ‘deep build-up’ which is also popular in the PL.

As we have said, there have been a lot of managerial changes, so this league could look very different next year. One club to keep an eye out for: Athletic Club finished eighth under the consistently excellent Marcelino but he has departed; they have recruited Ernesto Valverde, a two-times La Liga winner with Barcelona who should nudge them further towards the full control style, at odds with how Athletic usually play. In the Segunda, too, it’ll be interesting to see how or if Luis Garcia, formerly at Mallorca, now at Alaves, transitions an unsuccessful direct team into the more wide attacking style he employed last season.

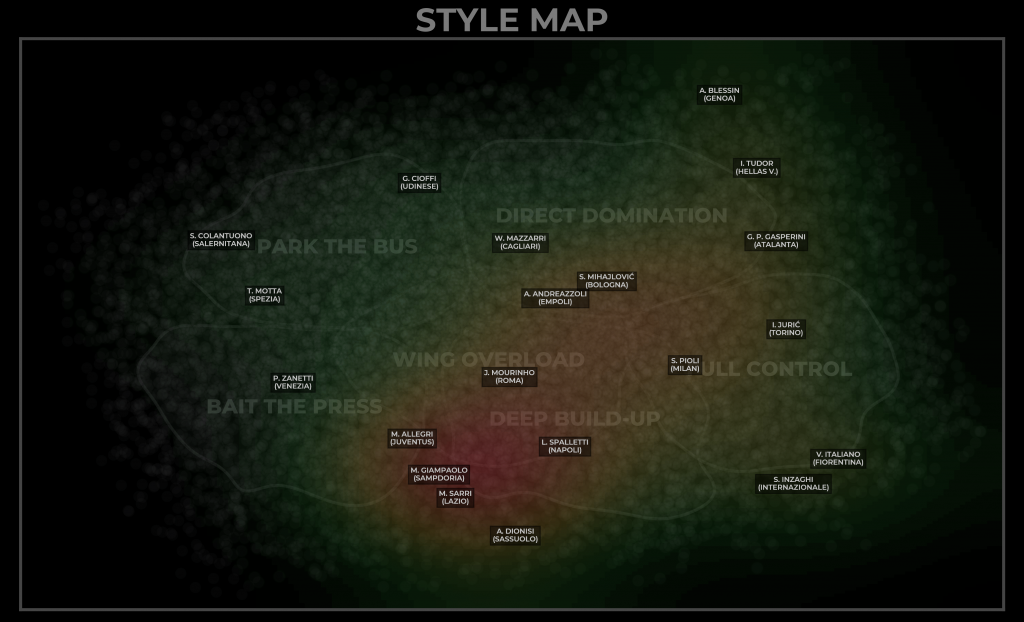

Serie A

There are two hugely surprising results from this analysis. Traditional Italian powerhouses Juventus sit in the same sector as Bruno Lage’s Wolverhampton Wanderers or Ruben Torrecilla’s Granada (Torrecilla left Granada in April). Max Allegri’s team uses a mix of wide attacks, sitting deep and encouraging teams on to them, while occasionally pressing high; this is not what one would expect a team that expects to dominate the league. The stylistic position of Guardiola, Nagelsmann, and Xavi is taken, surprisingly, by Vincenzo Italiano’s underrated Fiorentina team, with Simone Inzaghi’s Inter Milan also in the ‘good team’ sector.

Stefano Pioli’s title-winning AC Milan are on the intersection between ‘full control’ and ‘deep build-up’, while also incorporating some ‘wing overloads’. Interestingly, Jose Mourinho’s Roma are stylistically similar to the average Premier League side and almost in the exact centre of our style map.

Serie A has also lost its most interesting coach, Alexander Blessin (pictured above), who took Genoa down with a direct style unparalleled across Europe’s top five leagues. Genoa didn’t have the players to cope with his extreme approach, but he is a fascinating coach and one to follow in Serie B. Italy actually has more ‘direct domination’ and ‘full control’ coaches than one might expect, but also has a surprising number of teams who sit in the ‘deep build-up’/’bait the press’ intersection. These teams will play plenty of short passes in deep position, then look to hit it long, while also engaging in varying degrees of high pressing to win back the ball.

Two direct coaches, Blessin and Walter Mazzarri, took their sides down to Serie B (Mazzarri was replaced in May), while Paolo Zanetti, coach of Venezia until he was replaced in April by Andrea Soncin, tried to keep an under-powered squad in the league with a very defensive, counter-attacking system. The two most ‘park the bus’ teams just kept their head above water, showing that defensive solidity trumped direct, gung-ho systems in the Serie A relegation battle.

Serie A is definitely the most diffuse league we have looked at so far, with half the teams about as far from the middle of the heat map as is possible to be. And, while there are four teams in the rough intersection between ‘bait the press’ and ‘deep build-up’, no team sits in the centre of the red zone, unlike in every other league.

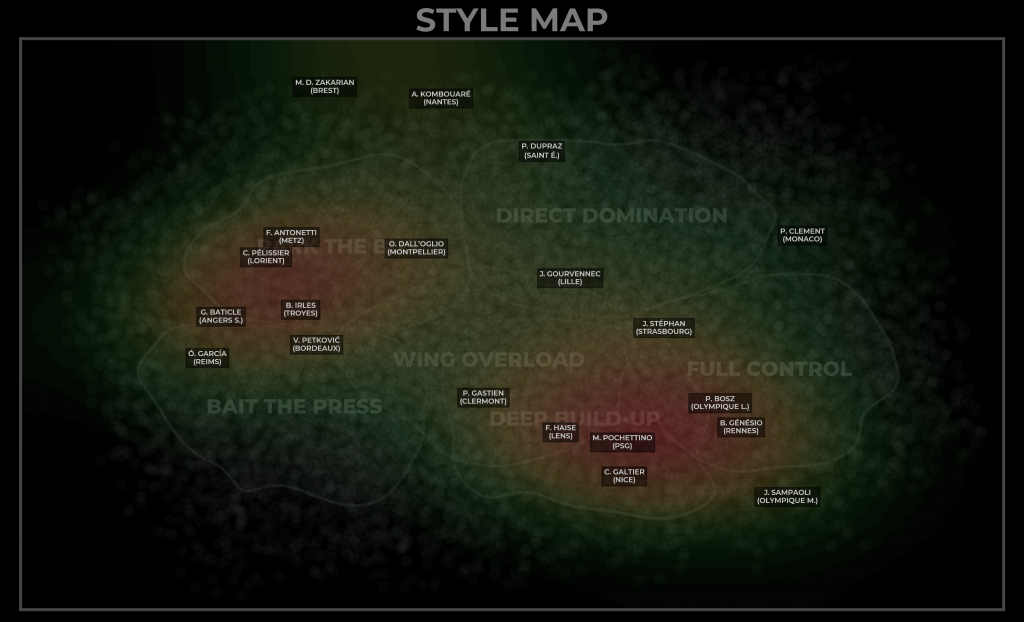

Ligue 1

But we have left the most interesting league until last: Ligue 1. Although Serie A is the most diffuse and the other three leagues have their surprises, Ligue 1 is the only league with two distinct, solid clusters, one around ‘parking the bus’ and the other around ‘deep build-up’, while it also has a couple of wild outliers.

Mauricio Pochettino is actually right in the middle of the deep build-up cluster, while another Bielsa disciple, Jorge Sampaoli, is closest to the far right-hand side, ‘full control’ position normally occupied by the best sides.

Ligue 1 is also the only league where there are no true ‘bait the press’ teams, while the closest to a ‘wing overload’ team, where there is combination play in wide areas and lots of crossing, was Pascal Gastien’s Clermont Foot, who narrowly escaped the drop. Off the sides who did go down, Vladimir Petkovic’s Bordeaux and Frederic Antonetti’s Metz were both in the ‘park the bus’ cluster, while Pascal Dupraz, appointed to St. Etienne in December, tried unsuccessfully to save them with a more direct style.

The Ligue 1 league table is worth looking at here, too. PSG, Nice, Lens, Rennes, Lyon are all around the ‘build-up’/’full control’ intersection, while Strasbourg and Marseille are ‘full control’ outliers. These teams occupy seven of the top eight places, with only Monaco under Paul Clement a pure ‘direct domination’ team. Interestingly, Nantes, under Antoine Kombouare, placed ninth with a very direct style that incorporated a deep defence and counter-attacking, while Stade Brestois came 11th with an even more extreme counter-attacking approach. Ligue 1 is the only league that seems to have a clear division between the better sides and the less successful ones, with two very counter-attacking outliers.

Next season promises to be interesting. Christophe Galtier’s Nice are stylistically very similar to Mauricio Pochettino’s PSG, which bodes well as the Paris-based side transition to the former. Lille have also replaced Jocelyn Gourvennec with Paulo Fonseca, so we might also expect them to drop lower on the Y axis towards a more sustained deeper build-up.

Conclusions

While, as we said, these heat maps aren’t definitive because of manager tenures, they do give a really good overview of team styles in Europe’s top five leagues last season.

Generally speaking, the Premier League and LaLiga are most similar, while the Bundesliga is less direct than one might expect, and Serie A is probably the most diffuse league stylistically. Ligue 1 is also diffuse, but with two clusters of teams, roughly divided in top half and bottom half, with some outliers.

In the Premier League and the Bundesliga, the winning sides are bottom right on the map. But in the other three leagues, the stylistic purity of the ‘full control’ approach has been eschewed by Real Madrid, AC Milan, and PSG, who instead use some blend of ‘wing overload’, ‘deep build-up’, or ‘full control’.

Relegated teams tend to be overtly defensive to stave off other sides’ attacking threat, or try ‘direct domination’, sometimes with some counter-attacking thrown in. This makes sense but also implies that poor squads that try to play really direct football often suffer.

We can also use these maps to thing about coaching changes. Should David Moyes leave West Ham, might they do well to recruit Antoine Kombouare, another overachiever with stylistic similarities? Verona played some marvellously direct football under Igor Tudor, now at Marseille; how will his approach gel with a Marseille squad used to playing a much more control-orientated approach?

These maps certainly show a lot of interesting patterns, but in future, we can delve deeper. It would be interesting to start to compare these kind of stylistic results with things like squad wage bills and transfer outgoings, to see if we could further see patterns in the groupings the analysis throws up.

Image credit: Shutterstock/Fabrizio Andrea Bertani