Neel Shelat analyses Danish team FC København and how their aggressive positioning has helped them balance domestic and continental demands

The position of being a dominant team in a league that is far from the strongest in the confederation is quite an interesting one. While most teams can commit to playing styles and game models they plan to stick with throughout a season across various competitions, such teams have to be a bit more flexible.

Even if we think through their cases at an incredibly simplistic level, the dichotomy they are faced with becomes clear. At some level, these teams have to prioritise by adopting a front-footed, attack-minded approach to continue dominating the league and domestic competitions or focus on the tougher continental competition by incorporating an element of pressure-absorption and counterpunching.

Indeed, this is a dilemma we see at the most elite level of the game too. Think of Real Madrid’s incredible Champions League campaigns and triumphs in the mid-2010s across a period of five seasons in which they were crowned European champions four times but only managed to add one La Liga title to their collection. At present too, we are seeing just how difficult it is to balance optimal approaches between a league and cup campaign in Manchester City, who almost seem better-positioned for the Champions League title than the Premier League title despite their vastly different fortunes in both competitions under Pep Guardiola. In their case, it appears that some of their tactical tweaks led by the addition of Erling Haaland have taken them to an approach that appears better suited to the more enthralling end-to-end knockout cup ties than the weekly grind of a long league season.

If even the world’s best teams with the best coaches and best players find it so difficult to stay at the top of their game in both the domestic league and continental cup (from a purely tactical perspective, let alone questions of fixture congestion and such), then what hope do the contenders from relatively weaker leagues have? For them, the disparity in optimal approaches appears even greater as we touched on above, and at the surface level, they seem diametrically opposed. It should be no surprise, then, that in the thirty seasons full season of the UEFA Champions League that have been completed so far, only once has a team from the Danish Superliga (currently the 15th-strongest league in UEFA according to their coefficient) reached the knockouts.

This season, defending champions FC København doubled their nation’s appearance record in the Champions League knockouts by advancing from an incredibly tough group that included Bayern Munich, Manchester United and Galatasaray. At the same time, they are right in the mix of a tough three-way Superligaen title race with FC Midtjylland and local rivals Brøndby. Most interestingly, they have impressed in both competitions by sticking to a consistent playing style and tactical approach, adopting the same formation in all but one game this season – the outlier being the second leg of their Champions League Round of 16 tie with Manchester City.

How have they managed to do so? The answer may lie in their rest attack.

What is Rest Attack?

Before we delve into what FC København are doing, it is worth addressing what rest attack exactly is. The term ‘rest defence’ has become quite a popular one and is now widely accepted to refer to how a team sets up in possession in preparation for defending against potential turnovers and transitions. The reason it is called a rather unintuitive “rest” defence, of course, is the fact that it is a direct translation of the German term “Restverteidigung”.

Quite simply, then, rest attack is the exact opposite – how a team sets up out of possession in preparation for attacking after potential turnovers and transitions. A cynic would say that this is nothing new, and back in the day it was simply called counterattacking. And to be fair to the cynic, they are not entirely wrong. Just like rest defence principles and ideas existed well before the term was popularised (such as one midfielder sitting back while the other one pushes forward), the same can be said of rest attack. Counterattacking is just one aspect of rest attacking because not every team wants to counter after winning the ball back. In fact, some even actively discourage counterattacking such as Manchester City in 2020/21, when Guardiola emphasised retaining possession rather than attempting risky passes in transition.

Part of the value of coining the term ‘rest attack’ is spotlighting the concept so as to give it more analytical focus. As is often the case, German tactics blog Spielverlagerung was among the first to explore this idea in detail through a Tactical Theory article by Judah Davies in 2022. In the piece, Davies explores various aspects of a team’s out-of-possession tactics that contribute to their rest attack, predominantly from the perspective of player responsibilities. He details the various stages and types of rest attacking transitions and the responsibilities of the players involved to execute them, ranging from winning the ball and playing through a potential counterpress to making off-ball movements to offer passing options or outlets.

Those are particularly interesting considerations from a coaching perspective, but from that, we can extrapolate a few details to focus on while analysing a team’s rest attack approach as a whole. Of course, we will start by examining FC København’s out-of-possession tactics to establish a framework, using which we will analyse specific details of their rest attacking.

FC København’s Out-Of-Possession Tactics

FC København are the best team in Denmark this season as far as the xGA figures are concerned. Their defensive approach in itself clearly is quite successful, though we will gloss over it relatively quickly.

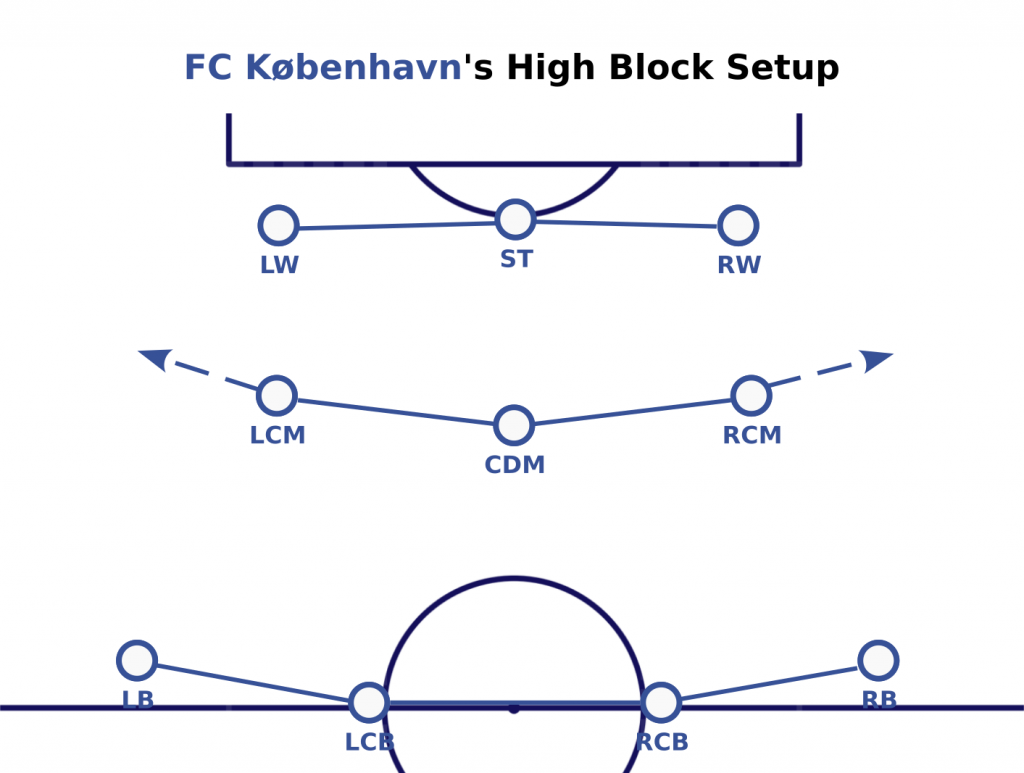

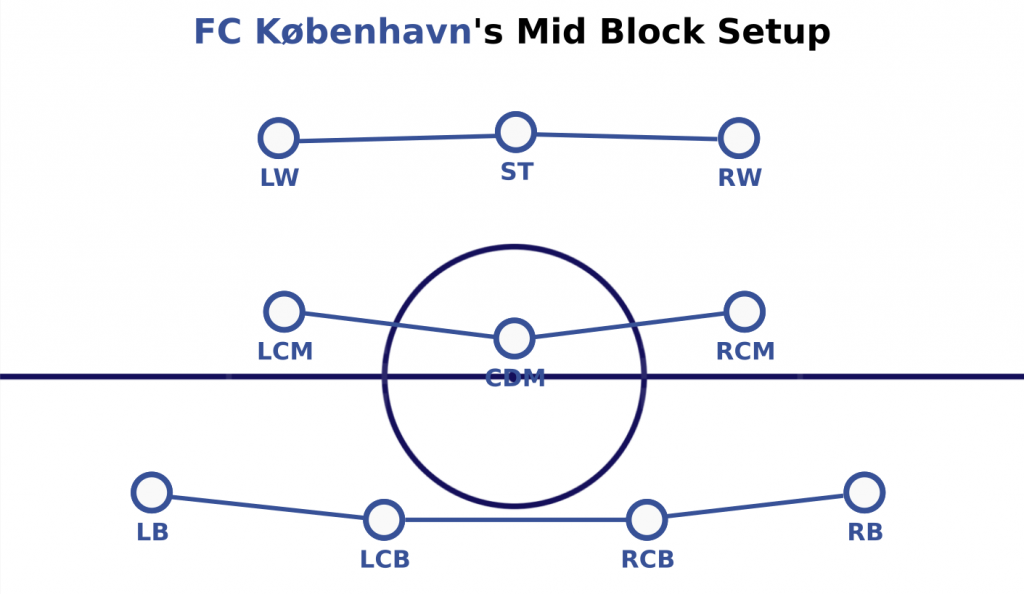

Like most dominant teams, København start defending as high up the pitch as possible. Against goal kicks and such situations, they set up in a 4-3-3 shape with an incredibly narrow front three which stays so in a compact mid block, before spreading out as the wingers track back wide in a 4-5-1 low block.

In the high block, their intention usually is to press. Of course, their setup can be minorly tweaked depending on the opposition’s build-up structure, but broadly speaking, they do this:

The narrow front three blocks off the centre (with the striker often sitting in front of the opposing defensive midfielder if the opponents are using a lone number six) while one winger makes a curved run to trigger the press. Due to the narrowness of the front three, the ball-side midfielder steps wide to cut off the opposition full-back’s forward passing/running options down the wing. If the opposition use higher wing-backs, FCK’s full-backs are prepared to jump up to them.

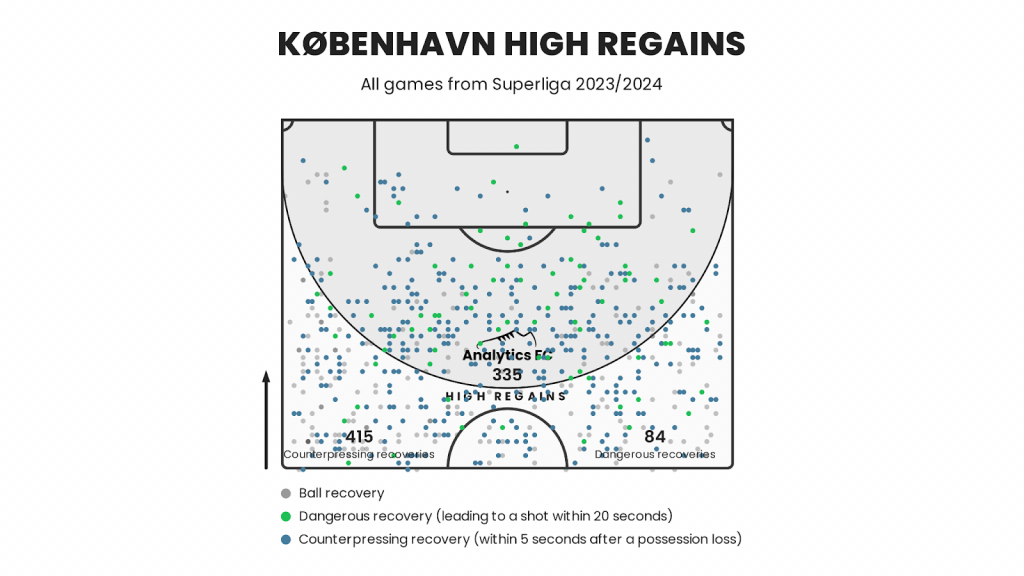

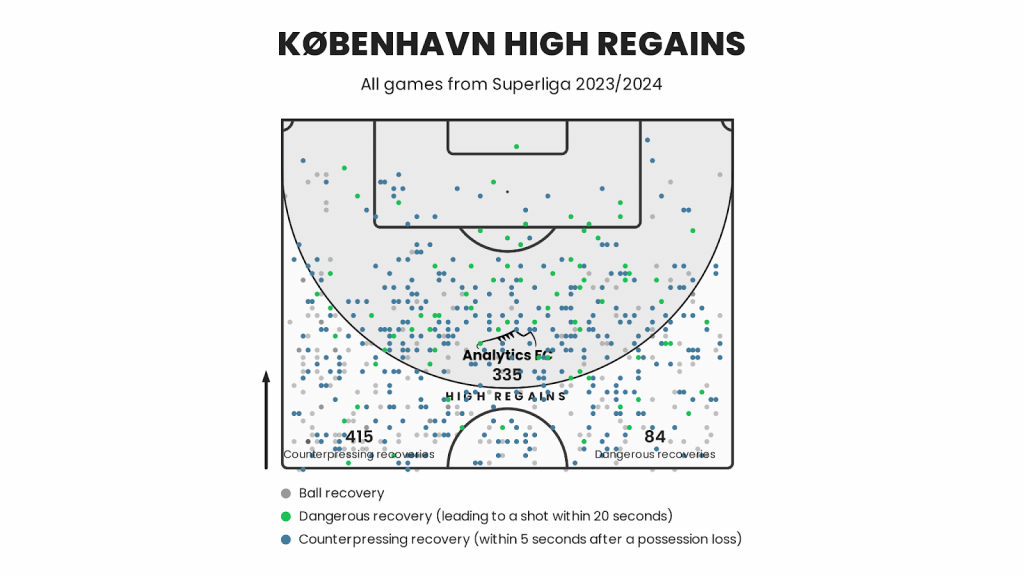

This pressing setup has been the most successful in Denmark’s top-flight this season, at least as far as high regains are concerned.

Crucially, København have struck a balance between applying a very successful press without needing to take too much risk. They do not intensely chase the ball but rather attempt to guide their opponents’ passing in a way that they play into trouble. So, if the press isn’t successful, FCK can easily drop into a compact mid block.

The principles here remain the same – the super narrow front three seeks to block off the centre of the pitch, while the ball-side midfielder is prepared to step out wide to close off the wing as nobody is positioned there in the starting setup of the block. If the opponents play a loose pass, the concerned winger or midfielder steps up to close the receiver down, hoping to force them back into their own box so that København can almost restart in their high block setup.

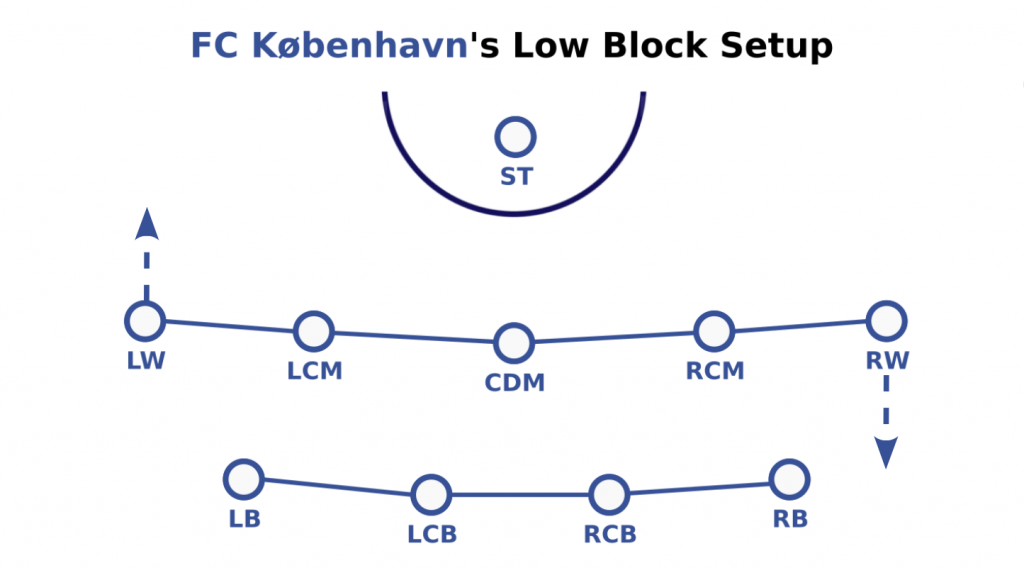

If no such thing happens and the opponents find a way into FCK’s half or even third, Jacob Neestrup’s side drop into a near-flat 4-5-1 low block.

The difference comes from the wingers tracking back wide because København recognise that they cannot afford to leave the wings entirely open in their own half and give the opposition’s wide players a free run at crossing. The ball-side winger often tracks back although to form a situational back five even, and at times FCK even switch to a 5-4-1 for good when they are looking to hold on to a lead late on.

At a very basic level, these are København’s defensive tactics. Assessed in isolation, they seem sensible and successful enough, but now we will see how they also serve to form an excellent rest attack.

FC København’s Rest Attacking

In each defensive phase, København’s structure is designed in a way to strengthen their rest attack. Let us assess each of them:

Starting in the high block phase, København’s super narrow front three means that they always have players in dangerous positions where they can receive the ball and immediately get a good sight of goal after a high turnover.

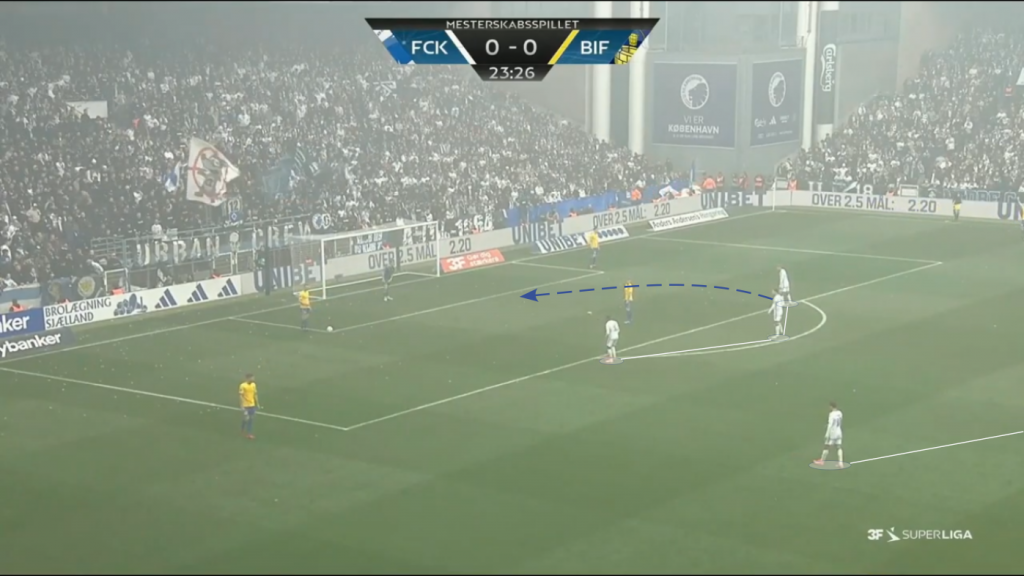

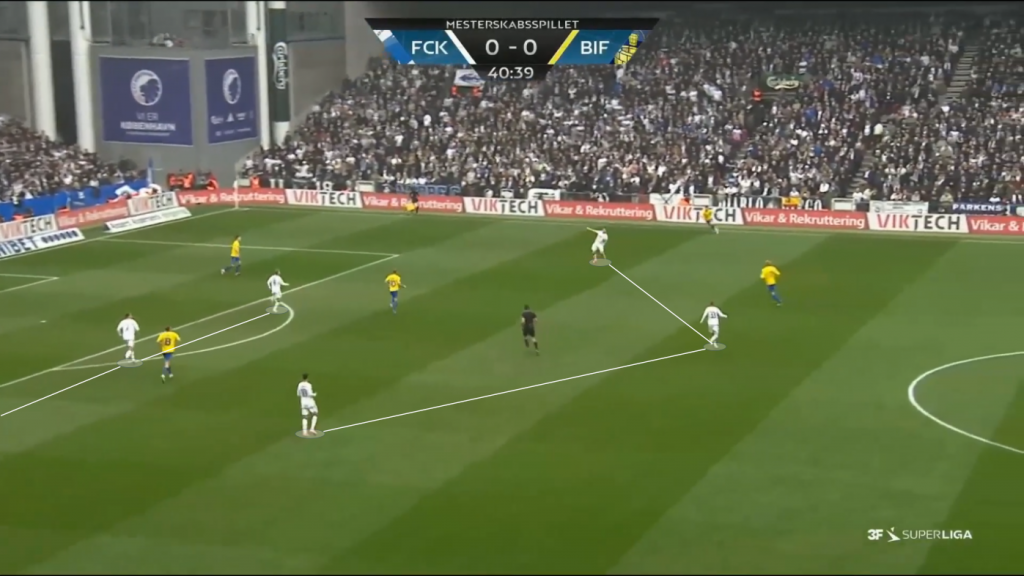

Take, for example, this instance where the right-sided midfielder intercepts an attempted switch from Brøndby’s defender, who failed to get enough distance under pressure.

At all times, FCK have five or six players in central positions in the attacking third, so the ball-winner can always see multiple routes to goal when he looks up. It should be no surprise, then that they have averaged 3.65 dangerous high recoveries (leading to a shot within 20 seconds) per game in the league this season. As the green dots in the below map show, these recoveries are dotted all over the pitch as FCK’s rest attack structure enables them to quickly access the central areas and create shooting opportunities.

In the high block phase, the goal of a good rest attack is to convert high turnovers into consistent shooting chances, so that is one part of the agenda checked off for København.

Moving on to the mid block phase, we start to see elements of counterattacking threat. The crucial distinction in the structure here compared to the high block is the compactness between the lines and consequently the proximity between various players in the centre of the pitch – particularly in midfield.

Besides ensuring that their opponents cannot play through the middle, this central compactness also ensures that København can retain the ball and play through a counterpress after a turnover. Even before considering attacking movements, the first phase of a rest attack (assuming it starts after a turnover) is to get secure control over the ball, preferably at the feet of someone who has time and space to look up and take a measured decision about the next action. The close distances in the front six enable the Danish champions to do this, making wall passes a simple possibility to ensure a clean escape from a counterpress.

Further forward, the narrowness of the front three makes them all an instant threat in behind after a turnover. Of course, they can be fed with through passes, but their runs can also open up space between the lines for other runners or even the ball carrier to access.

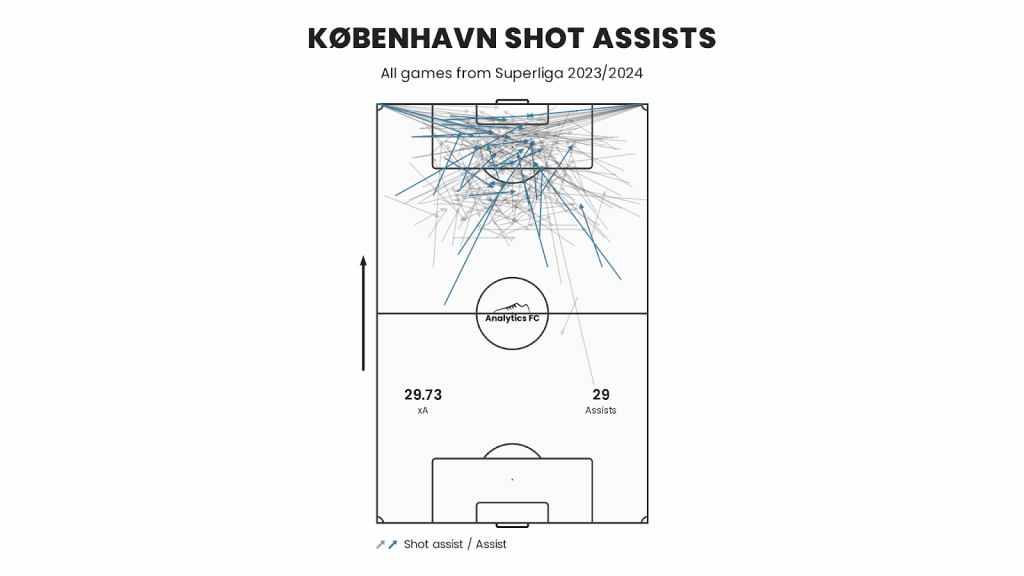

In this way, København’s counterattacking moves are really threatening because they can play through and get at the heart of the opponent’s rest defence. The outcome of this shows up in their shot assists map, as most of their key passes start and/or end in and around zone 14 – the central zone just outside the box which is considered the most dangerous area for an attacking team to access.

Finally, in the low block, the principle of central proximity is maintained with the three midfielders closing in, the striker willing to drop off to play a wall pass and the defenders looking to play forward after a turnover. That is quite evident in the first GIF we saw in this section.

The difference here, clearly, is the position of the winger out wide as an outlet. As aforementioned, FCK form a midfield five in a low block with the wingers going across to the wings and supporting their full-backs by tracking back fully into a back five if need be, but in such a case the other winger may look to ‘cheat’ – step up a little bit in order to get into a threatening rest attacking position.

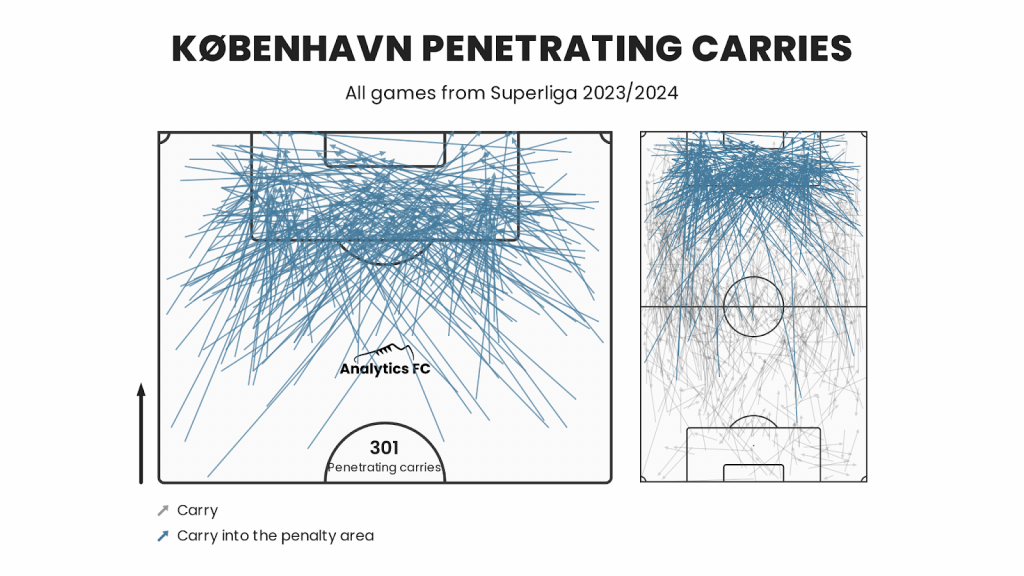

This enables the cheating winger to serve as an outlet after a turnover, so FCK’s transitions out of a low block often involve getting the ball out wide for the winger to carry forward. They do this so regularly that is shows up on their penetrating carries map – focus on the one on the right which shows the carries from their own half, which are clearly clustered down the wings.

Obviously, it helps to have excellent dribblers out wide for this, and FCK have precisely that in the likes of Elias Achouri and Roony Bardghji. The likes of Victor Claesson and Jordan Larsson can do a job from the centre too if need be, so København have the players to match their tactics in this case.

All things considered, FC København are an exceptional counterattacking team as their defensive structures in all phases are geared towards a strong rest attack as well. Their average of 1.62 counterattacks per game in the Superliga this season might not seem too high – it is on par with the rest of the league’s average – but when you consider the fact that they keep more possession than most others and therefore defend for a lesser amount of time, it starts to become impressive. The standout stat, though, is their conversation rate of counterattacks to shots which weighs in at a strong 52.05%, which is well above the rest of the league’s average of less than 40%. Indeed, they themselves are twice as successful at converting counterattacks to shots than positional attacks. Clearly, their rest attack has a big impact on their output at the sharp end of the pitch.

Discussion & Conclusion

As aforementioned, the fact that rest attack is not scrutinised a great deal (at least in public analysis spheres) does not mean that teams do not use these ideas. Whether consciously or otherwise, every team that plays football “does rest attack” because every team that plays football has to defend without the ball at some point. The approach and principles that København use are not a standard blueprint but rather a set that suits their playing style, players and tactics best, so upon closer examination, you may find that many teams do things differently while many others follow a similar formula.

In any case, rest attack should be considered an important phase of the game to consider when coaching or analysing any team. Its value for teams that defend more is quite obvious in the counterattacking potential a good rest attack can offer, but even the strongest teams that primarily aim to have possession-based dominance must also look to maximise their rest attacking potential.

For teams in relatively weaker leagues like the Danish Superliga, the value of such an approach becomes particularly evident in a continental competition like the Champions League where they have to face stronger opponents. But even for the world’s strongest teams, a good rest attack – be it to counterattack or retain the ball and transition into a settled possession phase after a turnover – can prove very useful when they get into heavyweight matches against equal opponents. Even in their other games where they expect to dominate, a well-worked rest attack can help with things like game management late on. As we saw with København, for instance, some of the examples came from the second halves of games against weaker opposition chasing the game, who FCK sucked in and counterpunched thanks to their counterattacking threat.

The football analysis sphere is an ever-evolving one that continues to zoom in on the smallest details of the game to find marginal gains. In such a world, rest attack must be an important component.

Header image copyright IMAGO / Michael Barrett Boesen