Dan Pritchard assesses Graham Potter’s tactical approach using data to show how he overachieved relative to budget with the Seagulls

Almost all football clubs at the professional level use data these days, but fewer are led by that data, used to its fullest potential. This is something that requires knowledge of both the data and the context from which it was collected. Perhaps the model outside the ‘big six’ for the use of data, combined with clever football expertise in the top flight, is Brighton and Hove Albion, a modest club with few historical honours.

This clever approach is to be expected under owner Tony Bloom who, together with Brentford owner Matthew Benham, made his fortune going against the conventional wisdom in the betting markets. Their syndicate were among the earliest to realise chance creation, rather than goals scored, was a better measure of a side’s performance and therefore ability to win matches. They used that insight, alongside other statistics, to beat the bookmakers and make a fortune. These days their chance creation measurement has been replaced by expected goals (xG), while the other stats their group measured by eye have become publicly available, bringing that knowledge to the wider football world.

So it is unsurprising that Bloom’s club Brighton are champions of a data led approach, achieving far above their resources. According to Caplogy, Brighton have the fifth lowest salary bill in the Premier League, some £43,230,000 annually. Last season’s ninth place finish on 51 points cost them £847,647 per point, the third lowest spend per point in the league behind Benham’s newly promoted Brentford and Leeds United. While their data-led approach has led to successes in areas like player recruitment and opposition analysis, perhaps their biggest success to date was transforming their game model by hiring the now Chelsea head coach Graham Potter.

In comes Potter

When Brighton sacked Chris Hughton in the summer of 2019 and replaced him with Graham Potter, a manager with only a single season of managerial experience in the English Football League after successes in Sweden, they were, by most conventional wisdom, mad. It was a decision that has paid off. Under Potter, Brighton, with far fewer resources than their competitors, consistently challenged for the top half of the Premier League. Perhaps even more impressive is the style of play they achieved. Potter quickly transformed a previously counter-attacking team into one that would eventually play with a possession and control that the likes of top flight mainstays like Everton have failed to attain with a much larger wage bill. At times Brighton under Potter, in play style, resembled the ‘big six’ sides who have far and away the most resources in the league, but they did so with far less access to top level on-pitch talent as a result of their lower income and smaller historical footprint.

This, it appears, is what caught the eye of Chelsea’s new owner Todd Boehly, who appointed the Birmingham-born coach to replace Thomas Tuchel in early September. Despite a high net spend this summer, it is doubtful that Boehly will run Chelsea as a loss-making entity as did their previous owner. He has spoken about maximising the pathway from the academy to the first team and putting data at the heart of operations. These are aspects that Potter seems well positioned for, but what was it about his coaching background and preferred style that put him above many other potential candidates?

In order to understand Potter and his coaching team’s background and style we should look to his years with previous club Brighton. He transformed the team, working with a new set of players. Fortunately, we can use data to understand how this was achieved. Of course, for analysts as well as clubs, the use of data is only one of a number of potential tools, and so we will seek to put these data in context. This will hopefully allow us to understand how, with their relatively limited resources, Brighton and Graham Potter managed to achieve so much success.

A changing style

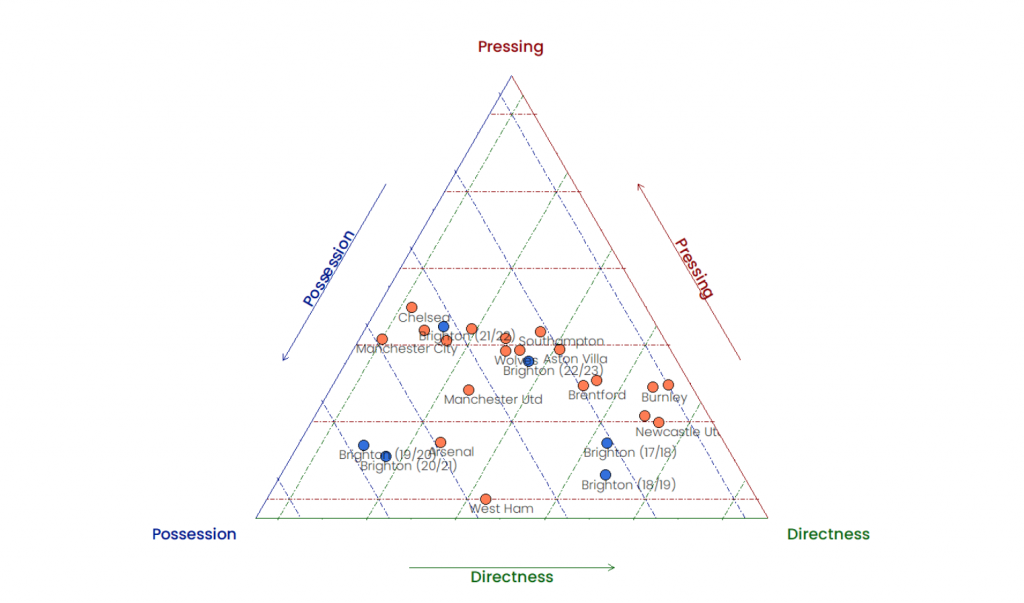

To understand what Brighton did we can look to the data to describe their style, and how it has changed, particularly in the transition from a defence-first manager in Hughton to a more modern possessional coach in Potter. While this is a very different task to the one he faces at Chelsea it should still shed light on how Potter adapts to an unfamiliar squad, and how closely that squad’s style comes to Tuchel’s Chelsea. We can do this by plotting the five full seasons (and their six 2022/23 matches) of Brighton’s time in the Premier League against the 2021/22 Premier League clubs for comparison in a ternary plot to see how they compare.

The ternary plot uses three axes of measurement calculated from FBref to form a triangle where the position of each side within the triangle, based on three measurements, gives a strong indication of their style (and those sides similar in style).

The first and clearest difference that can be seen in Brighton’s first two PL season’s under Hughton, compared to the subsequent seasons under Potter, is their directness, featured on the bottom axis in green, measured by their total passes per sequence (PPS – a sequence defined as events from gain of possession until loss of possession, stoppage in play, or a shot). On this axis there is a very clear difference between Hughton’s very direct Brighton and Potter’s. Brighton’s early sides appear alongside the likes of Burnley, Everton, Newcastle, and Watford, all sides that looked for fast attacking transitions to exploit space behind an opposition when gaining possession in the 2021/22 season. After their managerial change Brighton transitioned incredibly quickly to their new style, becoming far more patient and less direct. In their first season under the new manager, The Seagulls put together 11.9 passes per sequence, the third highest in the dataset after possession-heavy sides Manchester City and Liverpool.

Naturally, then, possession is the second clear difference as the side evolved, which is represented by the blue axis on our plot, measured by a team’s average percentage of possession. On this axis we come across a quirk of ternary plots with multiple interacting axes: on a traditional scattergram it would appear that the Brighton side’s from 2019/20 and 2020/21 have the greatest possession in our dataset, being the side’s furthest along that left axis. This is not the case, with last season’s top three Man City, Liverpool and Chelsea placing respectively the highest share of possession. Instead the interaction with the right-hand pressing axis causes the ‘big six’ points to not appear in the possession corner like those Brighton sides as they are also intense pressing sides too.

Therefore those Brighton sides (or any side situated in a corner) are more weighted towards possession than any other side in the data set, being both above average in that category, but without particularly intense pressing or direct transitions. While in 2019/20 and 2020/21 Brighton were notably more possession-based than under their previous manager, it is the side from last season that appears nearest the big six teams, clustering with Potter’s next club Chelsea (under the then coach Thomas Tuchel), and indicating an increase in their pressing intensity that season.

This brings us to the right hand pressing axis in red, which is measured by passes per defensive action (PPDA), a stat commonly used to determine the intensity with which a side looks to turn possession over. Here, Potter’s side turned up the intensity compared to previous seasons, taking a defensive action for every 8.76 opposition passes, where they were previously allowing 11.35 on average, slightly higher than the 11.48 allowed in their first two seasons. This is something that looks like it might have continued in Potter’s matches in charge this season, though the small sample size of opponents means we do not get a full picture. These data have shown us that Brighton’s approach to matches changed significantly, both in regards to possession and pressuring the opposition in the broad sense. However, in order to learn more about their style we should look at where on the pitch they are keeping possession and pressuring opponents, something that separating the pitch into thirds can help determine.

Using FBref’s pressures metric, it is clear that there is a different approach to where Brighton want to win the ball, despite the similar overall PPDA intensity of Brighton’s first two seasons and their next two. The 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons saw few of the side’s pressures applied in the opposition third, with a high number both within their own third and the midfield, as the side clearly sat deeper and transitioned into direct attacks. After Graham Potter took over the side, Brighton immediately began to apply more pressure to the opposition in their own third, and after dropping that intensity in 2020/21, pushed their high press further last season. That intensity is something that looked like it would continue this season, where Brighton have allowed 10.08 PPDA in their six matches with Potter, and continued applying that further up the pitch with even less pressure applied within their own third.

This high press and aggressive counter-pressing is a crucial aspect of many top possession-based sides, including Chelsea, who aim to win the ball back quickly, maintaining control and maximising the opportunity to create chances. The data support’s Potter’s suitability for a top European club but can only highlight what happened in terms of where Brighton were pressing and how that changed. Further context is required to understand how these changes were made to a previously counter attacking side.

Potter’s tactics without the ball

Before Potter took over Brighton would often defend in a 4-5-1 or 4-4-1-1 mid block which is supported by our data. The wingers spread wide to stop the opposition progressing down the wings and force them to play into a congested midfield space where The Seagulls could win back the ball. If the opposition got into Brighton’s final third, Hughton’s team were happy to retreat into a more narrow low block to try to force crosses that their aerially dominant centre backs were comfortable dealing with. The following season Potter made some key tweaks to this set-up but these were nonetheless familiar to the existing players.

The following examples against Manchester City and Tottenham Hotspur from the 2019/20 season show a broadly similar approach to Hughton’s, using wide players to block progression down the wings and force an opposition to play into a congested midfield. The details though are different, both in the flexible back three and the more commonly used back four formations of that season. Often the wing backs in a three/five or nearside full back in a four would look to block an opposition’s outball to the wing. The wingers or wide midfielders that would have blocked that ball under Hughton were instead deployed narrowly into a Red Bull-like box midfield while the forward(s) would prevent passes back to the central defenders in order to win the ball back higher up the pitch.

It was crucial to their new style that Brighton also introduced a counter-press when they lost the ball, rather than immediately returning into a defensive block. Similarly indicative of that change in style was how they used the ball after winning it back. Rather than creating a transitional attack like in gegenpressing systems, Brighton under Potter would choose instead to recycle possession and build an attack from there, maintaining control and denying the opposition the ball. These are all aspects that had already been introduced to the players at Potter’s new club, but this example nonetheless shows how he has previously tailored his tactical concepts to the players he has available.

We can see how this developed as Potter’s squad became used to the concepts by fast forwarding to last season. By then, perhaps the most notable aspect of Brighton’s style under their manager was their tactical flexibility on and off the ball. As we continue to focus on their off ball pressing, the data highlighted their more aggressive high press and increased intensity, something that can be seen in their pressing structure.

The two examples below from 2021/22 again highlight different shapes, a 4-2-3-1 in the 2-2 draw against Liverpool and a 3-5-2 in the 2-1 win against Arsenal. The tweaks made for both fixtures highlight one of Brighton’s key strengths in identifying opposition strengths and flexibly setting up to nullify them. For the Liverpool match, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andy Robertson were identified as key players in Liverpool’s build-up and attack. To protect against them, Brighton’s shape became an aggressive 4-1-4-1 with Enock Mwepu, making his first start for the club, pushing up from the midfield two to join the forward four. This allowed Brighton’s nearside wide forward to directly engage Liverpool’s full back while maintaining numerical parity with their deeper midfielders. To prevent this press being bypassed by long passes into Firmino dropping deep, Brighton’s other wide forward would assist the holding midfielder by moving back to maintain the two man midfield.

A different but similarly aggressive approach was taken against Arsenal, who having sustained an injury to Kieran Tierney were progressing the ball with the presence of Emile Smith-Rowe and Martin Ødegaard in the midfield three. This approach looked to contain Arsenal from playing out from the back by pressing in a man orientated 3-3-4, with the wing backs, who acted more like traditional wingers on the ball, pushed into the first line of the press, with their positions in possession dictating their role out of it. They would come relatively narrow when the centre backs were in possession to shield direct passes into the midfield. When the ball moved wide those wing backs were tasked with covering the opposition full backs, moving back into more traditional wing back areas.

The man-orientated press was seen again in the opening match of the 2022/23 season as Brighton defeated Erik Ten Haag’s Manchester United and a 3-3-4 structure was also used for Potter’s first Chelsea match against RB Salzburg. A key tenet of Brighton’s off-the-ball game model under Graham Potter was their flexible approach to shape and pressing organisation to nullify an opposition’s strengths, something requiring detailed opposition analysis and coaching to achieve. Brighton then aimed to recycle the ball after winning it, using possession defensively to limit opposition chances; this, however, is not the only goal of their possessional play so we should look at how they evolved on the ball.

Potter’s tactics in possession

Just as their off ball approach was tweaked within games and match to match, Brighton’s in possession model was similarly flexible: keeping and recycling the ball limits an opposition’s time to create chances but it also facilitates Brighton’s method of creating their own. To understand this we should look deeper at where Potter’s Brighton kept the ball and if they used it to create chances more effectively than their previously counter-attacking style under Hughton?

By understanding Brighton’s field tilt, or where they had possession of the ball compared to the opposition, measured by FBref’s touches for and against metrics, we can better understand their evolution. Again, much like their pressing structures, Potter’s influence is seen immediately, maintaining his side’s control within their own third but increasing the share of the ball by over 10% in the midfield third, and 9% in the opposition’s. Similar to their off-the-ball work too is how this control remained at similar levels in 2020/21 before growing again in 2021/22, controlling 46.2% of the ball in the opposition third, the highest of their time in the Premier League. Even the limited data from the 2022/23 season shows how Brighton were holding the ball well in the opposition third, even if their share of the ball in their own has dropped. The data again, however, leaves the question of how Brighton achieved this: what structural changes did they make and how did coaching transform players who previously were counter-attacking?

The first clear structural change for Brighton begins in their own third by playing out from the back. Playing the ball out from the back is a key tenant of possession styles, the aim being to both control the ball with shorter, less risky passes, and draw the opposition forward to create space between their defensive lines. Brighton were no different in that regard and this is an area where individual player stats can be useful to understand the shift in style. These radar charts for the three deepest players, the goalkeeper and centre backs (Brighton often played with a back four in Potter’s first season), measure the key passing metrics in Hughton’s final season and Potter’s first.

The charts not only highlight the significant style change between the seasons, but also the successful coaching under Graham Potter to bring out these abilities in his players. Matt Ryan was asked to launch the ball far less often, instead passing or throwing the ball out to his centre backs; those few launches were also into safer areas to retain the ball. Furthermore Ryan was instructed to be more proactive and to come off his line to assist in this possession-focussed style, coming out to stop crosses and make sweeping actions.

For centre backs Shane Duffy and Lewis Dunk, this coaching came in the form of a greater proportion of their passes played along the ground to nearby teammates. More of their passes were outside of their own third as well, with progressive passing only counted from 40 yards from the goal line. This higher line was one of the key structural changes made to Brighton’s build up to assist their players with the new style. Previously, the Seagulls often bypassed the centre backs to play quickly into the midfield from goal; they would then move the ball out to the wide spaces for progression, or even play long passes directly to the wings.

This would not do under Potter who began his time at Brighton primarily using possession defensively to deny the opposition time on the ball to create chances, something Chelsea have done plenty under Tuchel. The change in approach, to one of short passes out the back, is clear from the individual player data, though in order to facilitate this Brighton got plenty of players back to create those passing options. Often there would be as many as seven players within close proximity during early build-up phases to create passing triangles and diamonds; this patient approach was cautious but shows how Potter was able to adapt his game model to the players available to him.

His first season tested tactical solutions like Dan Burn’s use as a left back from a back three, before settling on more familiar 4-3-2-1-like formations. As well as changing their shape, Brighton added defenders who were tactically flexible and comfortable in possession like Burn and Adam Webster to a defence-first back line. This assisted the transition to possession football, but didn’t compromise their overall solidity much, as the whole team’s approach changed. As the side progressed in latter seasons they were able to be more expansive. Their early build-up phases would involve fewer players, often five. Despite the back three being Brighton’s shape on paper, the 4-2-3-1-like shape on the ball persisted, looking like the board below, though often tweaked to exploit opposition weaknesses.

In this example, another tactically flexible player, Marc Cucurella, who was being used as a wing back, took Dan Burn’s role as a left back on the ball and left centre back off it, adding his ability to invert and pack out the midfield. Cucurella is an example of Brighton’s excellent recruitment, finding undervalued players from unpopular sides. In Cucurella’s case he was recruited from Getafe, whose rather extreme launch-and-press style makes data scouting difficult. Brighton, though, were able to parse out which attributes of Cucurella’s game were tactical and which were useful to them. Having followed Cucurella to Chelsea, Graham Potter has again used his flexible positioning in this manner for his first fixture in change against Salzburg.

So is this flexible approach effective? Early on during Potter’s reign at Brighton keeping the ball didn’t quite have the hoped-for effect on their defensive performance. After a late season slump (during ‘Project Restart’ in particular), they conceded 1.43 xGA per 90, only 0.05 down from the previous season. This was something that improved with coaching time and recruitment, with chances conceded down to 1.19 xGA per 90 in 2021/22, having peaked at a low of 0.99 xGA per 90 in 20/21.

The other goal of playing out from the back, however, is to draw an opposition out of their block and create more space for attacking players. Brighton’s first season under Potter was more successful in this regard, creating 1.08 xG per 90, their first Premier League Season creating more than 1.00 xG per match. They would not drop below this figure again during Potter’s time in charge, though they often struggled to convert these chances.

The Seagulls again showed great tactical flexibility under their manager both between and within matches. Part of that was achieved by putting players into roles they are suited to rather than traditional positions. Attacking midfielders like Solly March, Pascal Groß, and Leandro Trossard came to make use of their skillsets in what on paper were unfamiliar positions but in roles that played to their strengths. In the above example they are deployed as wingbacks, but in and sometimes out of possession played as what might be termed a winger. Raheem Sterling has already been utilised in this fashion in his first Chelsea match under Potter as a wingback on paper, but on the pitch closer to a far more traditional winger role.

This flexibility was used by Brighton to maximise their strengths, and mitigate their weaknesses, as well as defensively to negate the opposition’s strengths and exploit their weaknesses. Opponents could not predict where a player might show up on the field even after seeing the team sheet. The result over Potter’s time with the club has resulted in consistently increased change creation compared to Chris Hughton’s transitional side, peaking with 1.36 xG per 90 in 2020/21 and reached 1.76 in the small sample of 2022/23 matches before Potter left the club. In this regard Chelsea present a different challenge as they will be technically superior to most opposition, requiring Chelsea to pull them out of shape to create, a major problem under Tuchel. This will require a particular emphasis on exploiting opposition weaknesses and it will be interesting to see how Potter attempts to solve this issue compared to his predecessor.

Potter and marginal gains

So how did Graham Potter and Brighton achieve the play style of a top side despite their financial disadvantage? Their recruitment used data excellently and went beyond the numbers to find tactical unicorns like Cucurella. Their opposition analysis combined data and tactical knowledge to develop a game plan that maximised their chances of winning. They also had a head coach that brought into the insights data provided, and expertly applied it in the context of his squad’s strengths and weaknesses. Our analysis here shows despite an impressively smooth switch in style, much of the flexibility and control Brighton demonstrated took time to implement.

It is easy to see why Graham Potter was continuously linked with clubs with more resources, and eventually picked up by Chelsea’s new owners with their intention to invest in a data-led approach. However, behind Potter was a club that patiently built itself into a Premier League mainstay by continuously making smart, interesting decisions. Their hiring of former Sassuolo and Shakhtar Donetsk manager Robert De Zerbi is likely to be just as fascinating. As for Potter at Chelsea, he brings with him the coaching ability to improve and get the best out of players in unconventional positions, a flexible approach, and the tactical knowledge to make the best out of that approach. Whether Chelsea build the backroom analysis to properly support him in this remains to be seen, but there should be little doubt about Graham Potter’s calibre.