Jamie Scott looks at a trend in the full back position and its implications for possession football

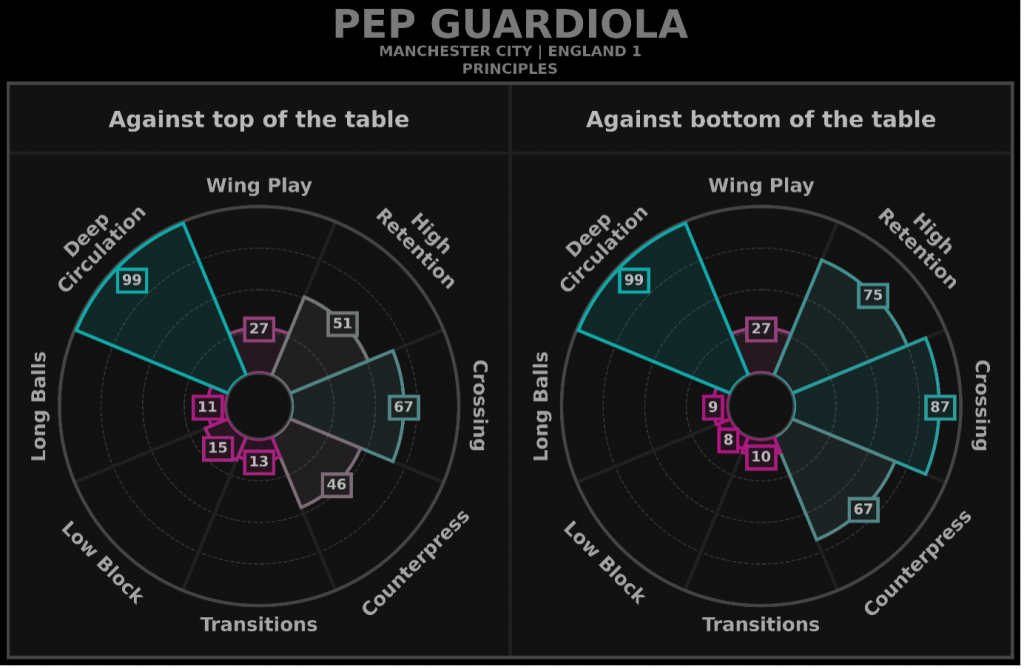

The role of fullbacks has become progressively more discussed, ever since Pep Guardiola made inverting fullbacks a mainstream phenomenon in the 2010s. In fact, the frequency of these discussions has made the inversion of fullbacks a staple topic when analysing modern positional play systems, perhaps to such an extent that the shortcomings of inverting fullbacks are almost entirely ignored, subsequently rendering the utility of explosive, wide fullbacks as entirely understated. This article aims to analyse the role of Premier League fullbacks within their systems, to understand the trends in effectiveness between inverted and non-inverted fullbacks.

Inverted Fullbacks

Inverted fullbacks are fullbacks which begin in a nominally wider (typical) position, before moving into the inside channel, half-space, or central space. The mere occupation of non-wide spaces is often seen as the primary feature of an inverted fullback’s play, but this is a slightly reductive notion. The movement a fullback will make from the wider berth, to a central position is often a key facet of the tactic. In making that movement, the fullbacks are less likely to be tracked inside, as the defensive winger would either have to vacate their wide position, or communicate to pass the fullback on to a midfielder each time the movement inside was made. A valid argument is that passing on players is a staple feature in any regular professional side’s defensive block, although the movement inside does also allow the inverted fullback to play much of their game ‘in movement’ rather than in a static position (such as a double pivot for example). In a real-game scenario, there is often more than meets the eye about the inverted fullback tactic.

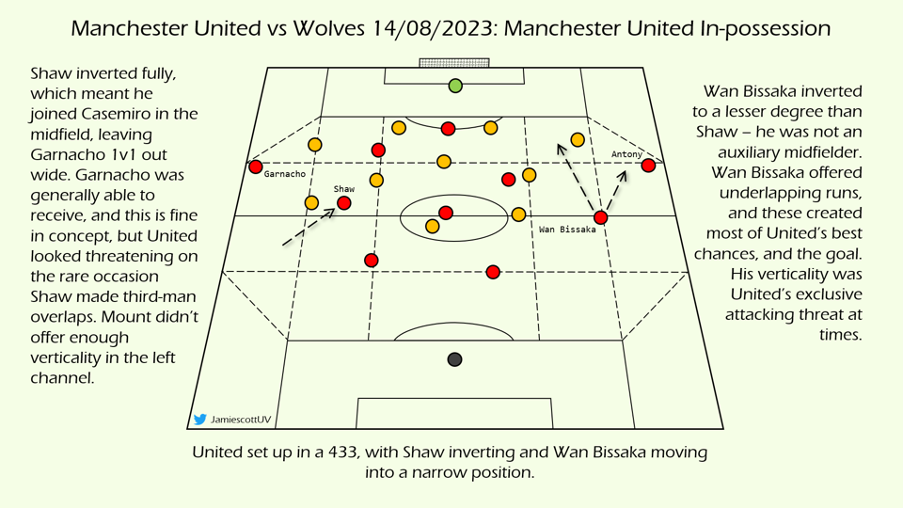

Luke Shaw and Aaron Wan Bissaka at Manchester United

At the beginning of Manchester United’s season, Luke Shaw played in an inverted role. Against Wolves in the season opener, it was an ineffective tactic. United already lacked inspiration in the progression phase as it was in that match, but this was exacerbated by the static nature of Shaw’s inversion. Wolves’ defensive block could easily screen Shaw out of the possession phase, by funnelling play wide. It may well have been United’s intention to open the passing lane to Garnacho on the left wing, who was able to receive 1v1 on regular occasions. Unfortunately, Garnacho had a poor game despite the 1v1 scenarios, and the lack of movement, in particular the lack of verticality surrounding Garnacho on the left, resulted in United failing to make much headway down their left.

With Aaron Wan-Bissaka inverting from right-back for United, it would seem logical that the scenario may have been similar on that flank too – but there were some subtle alterations that resulted in Wan-Bissaka’s inversion playing an integral role in United’s good attacking moments. Wan-Bissaka’s nominal position was slightly deeper and wider than Shaw’s in the build-up, which meant that he travelled further to invert. Combining this factor with the unorthodox (and unpredictable) nature of his movement on an individual level, Wan-Bissaka was able to receive on the half-turn, under less pressure than Shaw did, more frequently. This all culminated in Wan-Bissaka playing with more verticality, frequently underlapping Antony on the right wing. He created far more threat and was one of United’s stand-out performers (he also provided the assist that ultimately won the match for United). The stark contrast between United’s two inverted fullbacks perhaps highlights how subtle differences can lead to entirely different outcomes, even if the overarching tactics are the same.

Prior to his recent injury, Wan-Bissaka has been one of United’s standout performers this season. The loosely inverted role suits his player profile perfectly, and forces Wan Bissaka to always be in movement (which mitigates one of his primary weaknesses – as a player who often slows possession down by stopping the ball or chopping back, in 1v1s). The signing of Sergio Reguilon was scrutinised by many, but the vertical (and non-inverted) nature of Reguilon’s play has been a breath of fresh air for United, and has offered some vital fluidity and verticality on United’s left.

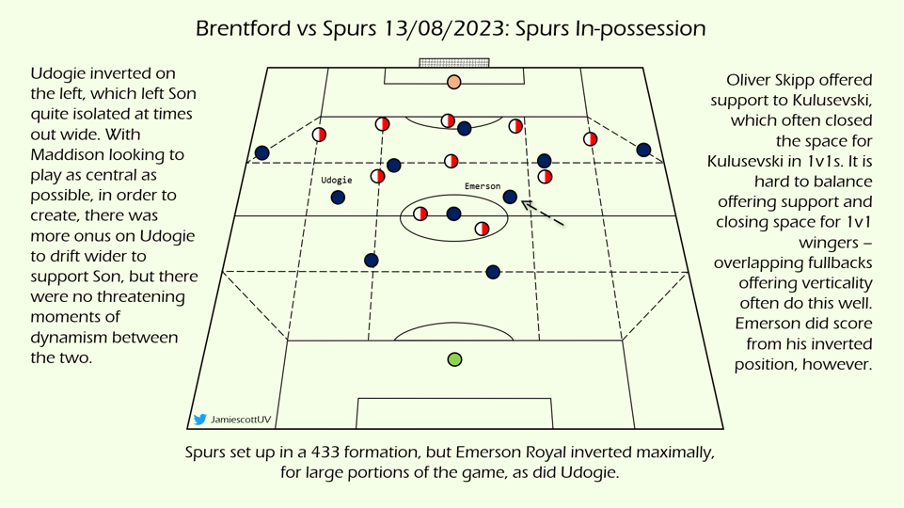

Emerson Royal and Destiny Udogie at Spurs

Under Ange Postecoglu, Spurs initially inverted their fullbacks to a maximal level, with Emerson Royal and Destiny Udogie inverting entirely into the central zone against Brentford in the season opener.

Much in a similar vein to Shaw and Garnacho’s relationship on Manchester United’s left, Emerson Royal’s inversion meant that Dejan Kulusevski was isolated 1v1, upon receiving, on the right. While Kulusevski is a phenomenal 1v1 dribbler, all wingers need a support ring (or some sort of off-the-ball movement in their vicinity, to disrupt the defensive block. Oliver Skipp provided this movement from midfield, vacating his position in the right half-space, which was subsequently occupied by Emerson Royal. Skipp then often underlapped into the ‘cut-back zone’, which narrowed the dribbling angles Kulusevksi could play at. The movement of Emerson Royal inside triggered Skipp to move on down the right, in a clockwork fashion. The tactical logic was sound, although the execution wasn’t ideal. Destiny Udogie inverted similarly from the left, leaving Son 1v1 on the left. Son was isolated, and struggled to get involved on the day (in fact, he has subsequently been moved to the #9 position, where he has had much more success). Son didn’t receive the support that Skipp offered Kulusevski, because James Maddison, Spurs’ left-sided midfielder, does not make decoy runs often, as he is such an effective creator on the ball in advanced midfield positions.

Assessing whether isolated tactical facets are effective is difficult, because of the dynamic nature of a football match, but the feeling regarding inverted fullbacks this season so far, has generally been negative – they are a tool to offer control, but often stifle fluidity and progressive play.

Conventional Fullbacks

A conventional fullback is one who holds width as the widest member of the defensive line. Because of the width with which they play, regular fullbacks perhaps take less of a role in possession phases in terms of ball retention and volume of passes, although they often make a large impact on the occasions they do receive, particularly in the attacking phases. This is generally because the fullbacks will have made a vertical run, from deep, to receive, meaning they are less likely to be tightly marked upon receiving. Because of the explosive vertical nature of their movement (particularly in third-man runs or when overlapping), fullbacks often execute riskier actions such as crosses or expansive passes, in order to benefit from the defensive disorder that often surrounds them. This role is completely distinct from the role of an inverted fullback, both in tactical inception, and in outcomes from dynamic in-game settings.

Kyle Walker at Manchester City

It would be slightly unfair to say that Kyle Walker’s rejuvenation at Manchester City has been a revelation, because Walker has been a top-class fullback over the last 5 years. However, after John Stones took the lion’s share of praise for his movement into midfield areas last season, the fact that Walker has made such an impact as a regular right back is not to be overlooked.

Walker’s natural skills are largely based around his physical capabilities – namely explosive pace and acceleration – and are complemented by his decision-making and game IQ. Walker maximises these qualities, by creating scenarios where he can make a real impact. The timing and selection of Walker’s vertical runs is impeccable, and this allows Walker to be a real penetrative presence from an attacking perspective. Against Burnley in the season opener, while Walker’s left-sided teammate Rico Lewis inverted rather seamlessly (in a quiet but effective performance), Walker made an impact in all phases of play, including creating a pre-assist with a well-timed vertical run to receive and cut-back into the danger zone.

While much of City’s play is predicated on control and central dominance, the vertical axis Walker plays on is a complete contrast, and works so well as a result.

Introducing verticality into a team’s play, in an effective and low-risk manner, is often challenging, so it is very surprising that more teams haven’t reverted to regular fullbacks, who can be this vertical presence with few risks associated, and a high upside in the attacking phase.

Reece James/Ben Chilwell/Malo Gusto at Chelsea

Chelsea are an interesting case study to analyse under Mauricio Pochettino this season – not least because their performances have been better than their results suggest. Their fullback situation is incredibly convoluted, and much of how we view it is based on semantics – there was debate surrounding whether Chelsea play with a back three or a back four, or whether Ben Chilwell was a wingback or left winger. Ultimately, voices from within the Chelsea camp articulated that they operate with a back four, with Levi Colwill at left back, and Ben Chilwell as a left winger. Ben Chilwell, perhaps as a result of the angles he receives at as a left-footed left winger, still operates much like a wingback, beginning from a deeper position than a winger typically would. Chilwell has been highly effective with his penetrative runs this season, arriving late, from deep, with well timed runs. Unlike Walker who can use his explosive burst to arrive quickly in attacking zones, Chilwell is more methodical and acts as more of a raumdauter from left wing (back). He infiltrates defence, often arriving late in the move, or when the second ball falls Chelsea’s way. From a deep and wide starting point, and how late he makes his runs, Chilwell is rarely tracked arriving in these scenarios, and has put up good underlying numbers so far – better numbers than his output suggests anyway.

Reece James, prior to injury, was highly threatening down the right too, acting as a deeper wingback than Chilwell (or as it transpired, a fullback in a back four). This, combined with James natural player profile, meant James was very effective in manufacturing attacking situations in his performance against Liverpool. He received and burst forwards, combining with Raheem Sterling, to arrive in dangerous crossing scenarios. Malo Gusto, who is a similar player profile and plays the exact same role for Chelsea, has been very threatening too, in his performances. It seems slightly reductive to attribute the contrasts in Chelsea right and left fullback/winger’s role to the name given to the positions – Chilwell’s player profile largely contributes to his differences to James/Gusto anyway. Finally, it is also worth noting that Pochettino’s previous Premier League stint saw him use a 4231 – 343 hybrid, where Eric Dier dropping into the back line from midfield triggered the fullbacks to be pushed higher, and a back three to form. Neither of Chelsea’s double pivot drop in to induce the switch to a three at-the-back in their system, but a back three of Disasi, Silva and Colwill has certainly formed at times, and the performance of Chilwell in his left winger/wingback role can be used in evidence for the utility and effectiveness of authentic, non-inverted, fullbacks.

Summary and Conclusion

Inverted fullbacks can be incredible tactical tools to implement several key superiorities on the football pitch, including numerical superiorities (overloads) in central areas, leading to organised possession play, and a strong rest defence. Additionally, inverting fullbacks can open new and different passing lanes, particularly to a team’s wide players, who can receive in 1v1 scenarios. That said, the inversion of the fullback can also lead to the wide player being isolated, without a conventional security ring or off the ball movement in their vicinity. While midfield runners can compensate for the lack of off the ball movement near the winger, in lieu of a typical overlapping fullback, this can also cause nuanced issues that need tweaking within the team. Not every team has the ruthless, fluid efficiency of Pep Guardiola’s 2021/22 Manchester City, where Cancelo, De Bruyne and Bernardo Silva would rotate with the efficiency of a revolving door on the right. This season, teams have defended particularly well against inverted fullbacks, preventing passes into them, thus preventing effective progression through the middle of the pitch. This has often been exacerbated by lack of fluidity in the movement in sides struggling to progress play.

Conventional fullbacks, by contrast, have had a substantial impact this season. The verticality they offer with late runs, is often conducive to the fullback arriving in threatening positions, often with enough time to execute a key action such as a cross, shot, cut-back or penetrative pass.

It is certainly up for debate why conventional fullbacks have appeared to be much more effective than inverted fullbacks thus far this season. One simple reason, that may dispel the entire premise of this notion, would be that inverted fullbacks don’t get in as many attacking positions, due to the nature of their role. Because of this, their impact is less apparent than racking up goals and assists, or making explosive overlapping runs. Furthermore, the sample size is still quite small this season, so the apparent advantage of using conventional fullbacks may just be in player performance in these roles, so far this season. Further, perhaps player profiles of fit fullbacks in the elite sides in the Premier League may well just be better suited to a conventional role, thus higher performance levels at this stage in time. Time will tell whether this is just a blip, or a larger trend, but for now, the qualities regular fullbacks offer seem to be generating a greater positive impact in possession, than that of inverted fullbacks.

Header image copyright IMAGO / Micah Crook / PPAUK PPA