Abdullah Abdullah looks at an interesting player trend in the WSL and examines the case of Maya Le Tissier

How teams use certain formations and personnel can be closer to each other than we think and in the 2022/23 Women’s Super League season, it is certainly the case. Slightly longer managerial tenures mean that coaches are able to implement and enhance their ideas further and given a summer of spending, they’re arguably more able to put the finishing touches to what they deemed was missing. As a result, the top four of the WSL have so far performed consistently at a high level.

Arsenal Women, Chelsea Women, and Manchester United Women have only lost one league game each, while Manchester City Women are just behind with two. Tactically, each team have differing core tactical setups, be it their shape or philosophy, but there are strong similarities between three of the four teams, too: their centre-back profile and partnerships.

The traditional positional switch has often been the centre-back to the full-back. We have often seen players move into a wider position, with some of the world’s best having been transformed in this manner. There are many examples in the men’s game, but the full-back to centre-back switch hasn’t been as evident. Much of this comes from the fact that full-backs are much more inclined to push forward and give more in an attacking sense. There may also be issues of height or aerial dominance, as full backs are often shorter.

Nonetheless, it happens. David Alaba and Sergio Ramos are two of the most prolific examples of a successful switch from full-back to centre-back in the last decade and both in their own right have arguably become better players. Reece James and Luke Shaw have done similar jobs sparingly, so one might observe what is a rising trend, especially when using a full back as a wider centre back in a back three. And should be no surprise that the women’s game is now also seeing this evolution in tactical innovation; year after year, we’re seeing managers’ tactics becoming much more refined, and this evolution is just another sign of this improvement.

The move makes sense, as you get the defensive solidarity and positional sense when defending (covering) the wider areas. You also get the ball-carrying traits of a full-back that can help bypass the press in an alternative manner. The back four is as much about attacking as it is defending in the modern era. The word ‘balance’ is often bandied around and while it is an overused term, it’s the norm amongst most defensive structures. More often than not, teams will use one full-back as an auxiliary winger whilst the other will be more conservative.

This structure and setup correspond to the tactic of being interchangeable between a back three and a back four. Teams need to be flexible given how much teams are starting to use the back three and are playing a set of players who are comfortable playing as both full-backs and wide centre-backs. The switch from a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1 to a 3-2-5 when in possession is becoming the norm. Chelsea are an example of a team that has very regularly employed this system interchange on a regular basis. Emma Hayes’ use of Magdalena Eriksson as a pseudo-left centre-back and left-back coupled with Guro Reiten at left midfield/left wing-back allows them the flexibility to switch from a four to a three and vice versa. Moving a full-back inside to play as a centre-back brings their ball progression and wide space-defending skills into play.

Flexibility out of possession becomes a key factor in a player’s repertoire and arguably it’s the full-back that needs to be the most flexible. Their ability to switch between full-back and centre-back comfortably opens up teams to be tactically advanced. The example we used with Chelsea earlier is our main case study for the concept of flexibility.

This example shows Niamh Charles moving into a left wing-back position with the centre-back Eriksson taking up a full-back position to cover both positions and make sure that the gaps are filled. This shift allows teams to easily make the transition whilst retaining their shape and chemistry within the team structure.

When you have a full-back playing inside as part of a back four, their ability to understand the defensive space in behind the wide area makes defending that part of the pitch easier. The marauding full-back is a core part of most technical setups and needing to defend the space in behind them becomes more vital. Yes, traditionally the space is defended by a central midfielder but the oft-used, 2-3-5 in-possession transition system can see an extra midfielder push forward too. This means the 4-6 structure is heavily predicated on intelligent and quick central midfielders and centre-backs in defensive transition.

The spaces occupied by these midfielders mean they need to stop the central counter-attack as well as the attacking wide players, all without allowing the potential overload to get the better of the defence. Usually in these situations, defensive teams will delay the attack before reinforcements arrive and stop the wide attackers from attacking space, making the 1 v 1 ability of the player important. Centre-backs are renowned for their 1 v 1 defending of course, but the positions taken up by a full-back in that area are much more proactive compared to the traditional centre-back.

On top of that, you get to exploit their ball-carrying and passing capabilities. One virtue of the modern full-back is the ability to burst forward in attacking transition and start in a higher position from build-up. The concept for the modern centre-back is often to get on the ball in numerically overloaded situations. One key responsibility, then, is to drive forward with the ball when they have space to do so. In the case of a converted full-back, they can get the better of most opposing centre-forwards and midfielders, given their excellent ability in 1 v 1 situations. This is arguably their most crucial trait in possession and transition.

The propensity to step forward into space and have the option to either play vertically through progressive carrying or passing from a higher point of contact gives the in-possession team a different angle. Their turn of pace and dribbling are highlighted traits that come into the fore, which turns into a major press-resistance alternative. It shows us the player’s ability to break defensive lines and push the entire team forward by a few yards through a single move.

I don’t feel like two full-backs at centre-back is a possibility in a back four because centre-backs themselves are still integral cogs and bring their own advantages – for one, they’re usually more physical – but the option of having versatility and a unique set of traits is very useful and if clubs do play them, they’ll be assured of pace and excellent ball progression.

Maya Le Tissier

This season, Manchester United and Manchester City have both converted their full-backs into central defenders as Maya Le Tissier and Esme Morgan respectively have both been trialled and used in central positions (Alex Greenwood is another example of someone who can play in either role). Arsenal made a similar move last season with Steph Catley; the move has seen teams look to try and capitalise on their own tactics but also give them an advantage in build-up and defensive transition. Given that traditionally there’s been a transition of centre-backs being converted into full-backs, we’re now seeing the opposite for the reasons mentioned above.

But we’ll focus on an ideal example of Manchester United and their use of Maya Le Tissier. Manchester United stunned the crowd at the Emirates in November when they beat Arsenal in what was billed as a stellar away performance. The day will be remembered for the extraordinary effects of Ella Toone and Alessia Russo, but the team’s defensive display that day as a collective was simply exquisite. A stark difference in the back line was summer signing Maya Le Tissier situated at centre-back, who has excelled so far.

Marc Skinner’s move to covert a talented young full-back into a central defender came somewhat as a surprise, but her performances so far have warranted the move. She mostly played as a full-back for Brighton & Hove Albion but given the strength United already have in Maria Thorisdottir, Hannah Blundell, and Ona Batlle, moving Le Tissier centrally came down to a couple of reasons.

The first is the technical upgrade from the Maria Thorisdottir/Aoife Mannion partnership. While both were good defenders together, their collective lack of pace and, at times, positioning errors resulted in some poorly conceded goals. While they conceded a reasonable 22 goals last season, which was joint-third with Manchester City, they could have defended better in several moments, and if it weren’t for a few key saves from Mary Earps, it could have been more. To the naked eye, there seemed to be more attempts at last-ditch interceptive tackles from crosses from a defending perspective.

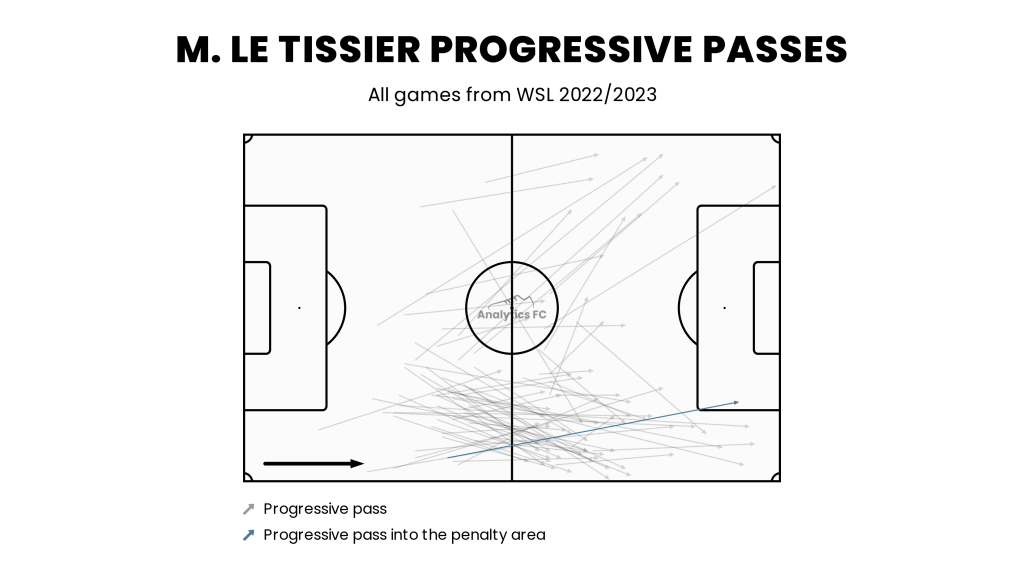

What we can gather here from Le Tissier’s profile from the TransferLab tool is that she’s classified as a Ball-Playing central defender with a score of 96 against other WSL centre-backs. For anyone to be ranked in the 95th percentile or higher means they’re one of the best in their position. Let’s break down the statistics even more. The English defender’s best attributes are her Carries, Forward Passes Received, and Headers – Open Play defending. The first two categories are very much tied to her ball-playing abilities and indicate that she’s mainly there to ensure there is progression out from the back. Neither Mannion nor Thorisdottir were particularly impressive in their progression play, often opting for safer passes.

The radar comparison chart highlights the profile of Thorisdottir and Le Tissier to showcase their play style which at first glance shows an obvious difference between defending and progressive play. The Norwegian defender is comparatively a better defender, but Le Tissier is a better passer. Though defending is an obviously important aspect of the position, the job of a central defender is also being able to carry out both traits and given the presence of Millie Turner as Le Tissier’s partner, the defensive burden is shouldered by her while Le Tissier takes on the progressive defender role.

Even by looking at their comparative numbers from centre-back between last season and this season, Le Tissier is already averaging more Passes to the Final Third (7.77 p90 vs 6.49 p90), Forward Passes (25.36 p90 v 20.17 p90), and fewer Long Passes (8.39 p90 v 8.70 p90) in the WSL.

Though there is the added caveat of minutes played given we’re comparing Thorisdottir’s 2021/22 season and Le Tissier’s 2022/23 season, it still provides an indication towards the reasoning behind moving the former Brighton & Hove Albion full-back into a central area.

We may still see more examples of this conversion in future seasons, but the move itself isn’t as easy as it seems. It requires full-backs with a unique skill set, and most importantly, intelligence in positioning with speed. Who becomes the next versatile breakthrough star is anyone’s guess.

Header image copyright IMAGO/Jessica Hornby/Sportimage