Jamie Scott looks at how England tweaked their midfield set-up to great effect in a World Cup opener against a defensively solid Iran

England opened their World Cup campaign with a comfortable win over Iran. Perhaps more importantly, there were some notable tactical takeaways from this game, that suggest England could well be a top side in this tournament.

Iran posed little threat, yet because they are (in principle) a well-drilled defensive outfit, England’s in-possession facets were tested to a reasonable degree, particularly in breaking down a defensive block. For this reason, a reasonable amount of credence can be given to an interpretation of England’s tactical performance being largely by coached design: there was little chaos and individual inspiration didn’t take over from team intentions.

It is therefore of interest to analyse England’s setup and discuss how they might continue to play throughout this World Cup.

Build-up

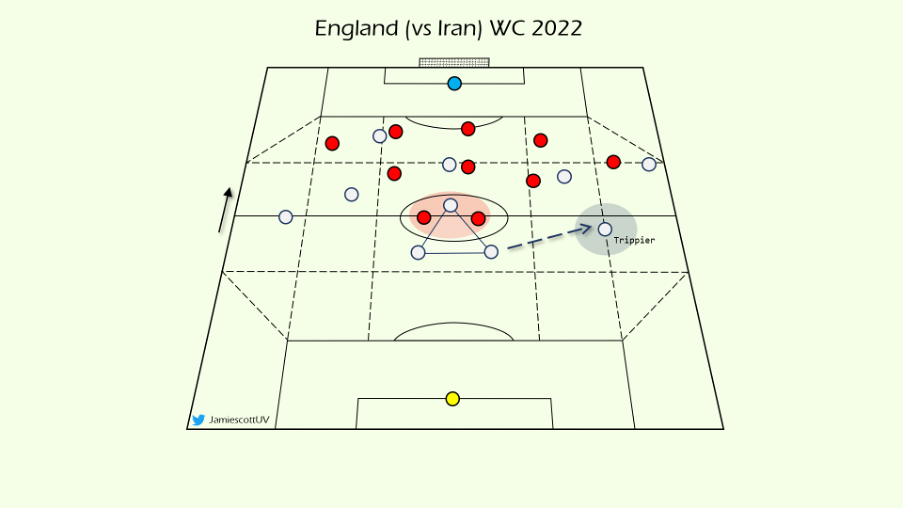

In build-up, England generally utilised a central component versus Iran’s first line of pressure. In many circumstances, this was limited to the two centre backs Maguire and Stones, with a midfielder dropping in to support. Because Iran used a 5-3-2 defensive block, England could create the 3v2 overload, with a midfielder dropping in, to progress past the first line of pressure and enter the Iran half. Declan Rice, the #6 for England, was obviously the most present when creating build-up structures with the centre backs, although Bellingham was also notably involved, dropping into the right side of the back line to create a three.

Creating a back three is an archetypal method of creating an overload to bypass an opposition front two. At times, Bellingham would remain higher up the pitch and Rice would play as the lone pivot in midfield. When Rice did not drop in, England were found in a 2-1 build-up structure. In this scenario, Rice remaining in the midfield forced the Iran strikers to use their cover shadows to screen passes into Rice, meaning they had to stay more central and press England’s centre backs from a central berth. This meant England that could progress the ball out to the fullbacks Shaw or Tripper. This incidentally worked very well, because Iran’s 532 block meant the fullbacks could receive on the half turn when dropping deeper and wide to receive, and England could easily progress into Iran’s half and establish possession in an attacking phase.

Iran did force a couple of nervy moments with their press, and this could be something for England to address. Playing out through a press requires strong tactical principles combined with composure and execution. Fortunately for England, Iran’s press only induced mistakes in England’s execution, something that is far easier to amend game-to-game than a poor overall tactical set-up.

In fact, England were tactically sound against the press, with Bellingham often dropping into a more central position in such a scenario to offer Rice support in the pivot. This meant England retained a stronger rest defence, numerically and in terms of compactness, while Bellingham also dragged an opposition midfielder higher up the pitch into England’s half. This gave Kane, Saka, and Sterling more space to create should the more direct pass into them be made.

Is England’s midfield conundrum solved?

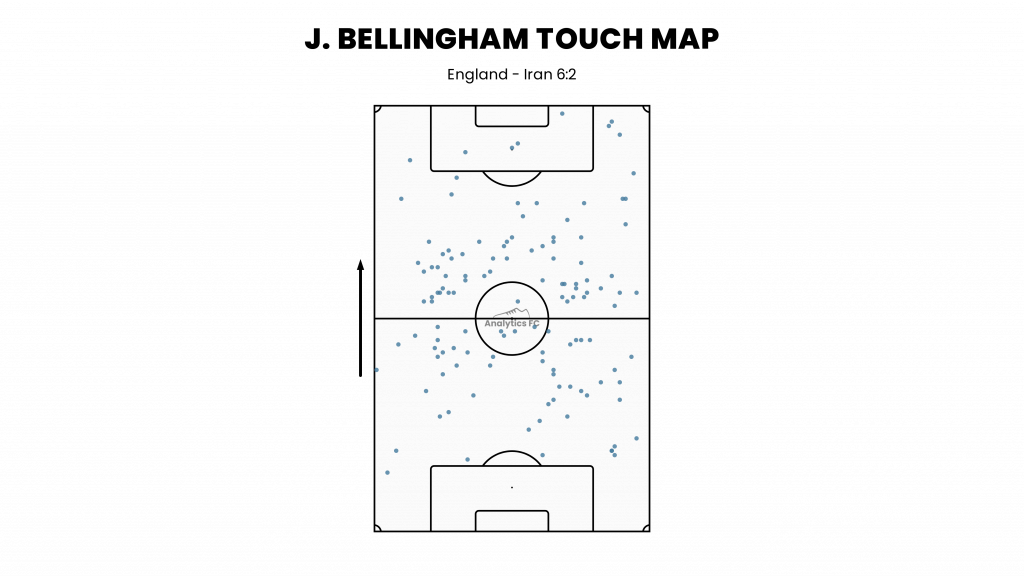

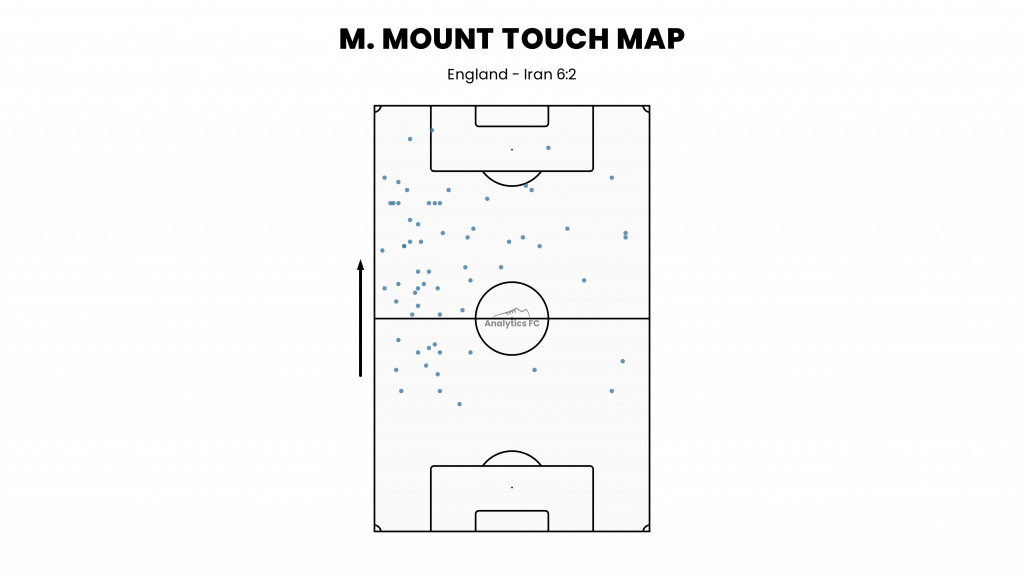

England had previously persisted with a midfield double pivot in tournaments under Gareth Southgate, and while this did offer security in tough games, it also meant that England appeared somewhat cautious when breaking down deeper blocks. Perhaps due to personnel changes (notably the continued rise to prominence of Jude Bellingham), England have reverted to a more classic 4-3-3 approach, with Mount and Bellingham flanking Declan Rice in the centre. The contrast in functions between Bellingham and Mount is perhaps the single most interesting tactical facet of England’s play, and therefore deserves an entire section of analysis.

A classic 433 often comprises of a #6, an #8 and a #10. This approach is asymmetrical; the #10 will sit higher than the #8 who will play on the opposing side of the #6. For England, Mount was more advanced in the left channel than Bellingham was on Rice’s right.

Bellingham took plaudits for his goal and pre-assist (as well as his extremely accomplished performance as a 19-year-old at the World Cup of course), but mount was equally effective in design. Bellingham had a far higher involvement than Mount in build-up, yet maintained a presence in the progression phase and actually popped up in the box with surprising regularity. Bellingham played like a box-to-box midfielder, and balanced his responsibilities very well. One thing that allowed Bellingham to pop up so effectively in all three possession phases so effectively was his role clarity. To Bellingham, it was perfectly clear when he was required to support in build-up. When he vacated the early possession phases, he pushed up the pitch with conviction; this not only dragged his marker away (thus creating space for others), but also meant Bellingham was primed to make an impact in ball progression or by popping up in and around the opposition penalty box in attacking moves.

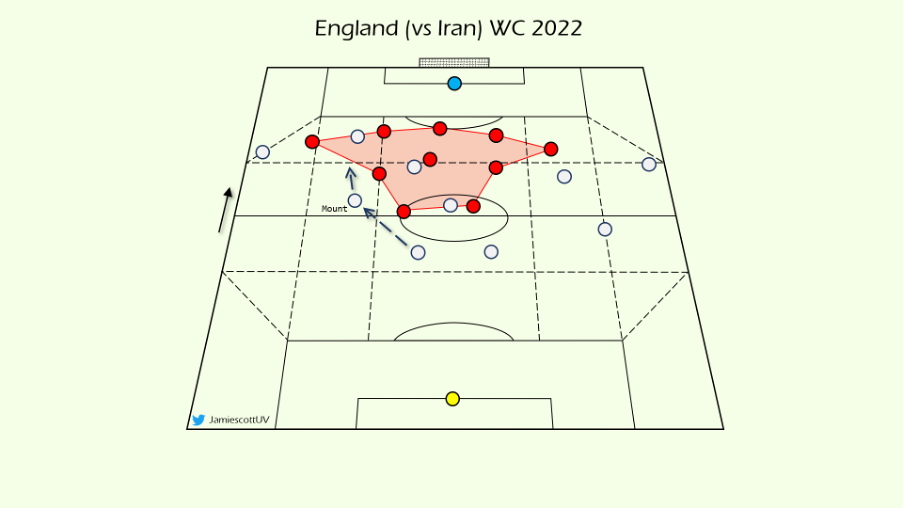

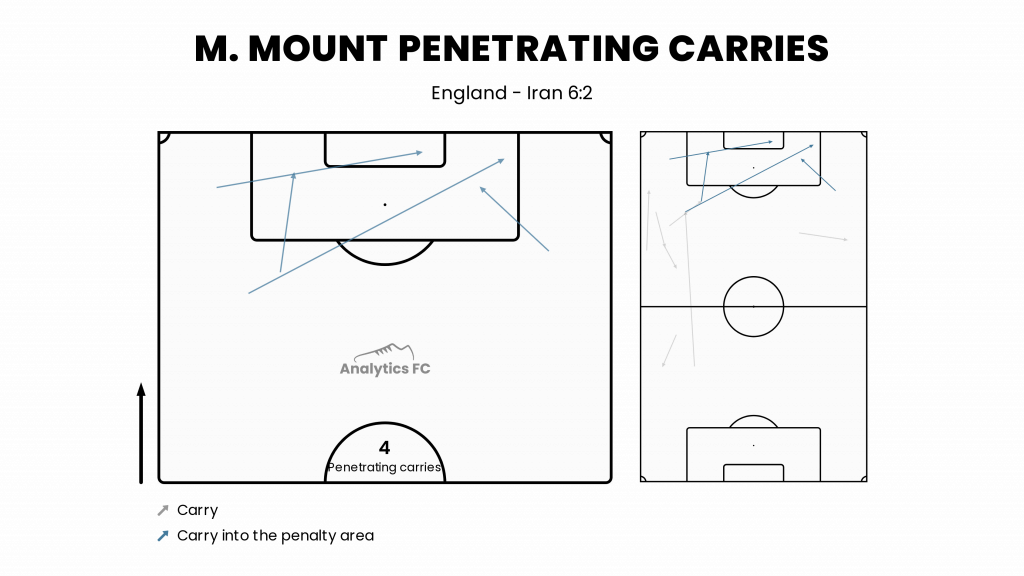

Mason Mount meanwhile played as more of a #10, but interestingly, was if anything less ‘creative’ than Bellingham. Mount on the other hand, was much more of a facilitator; in other words, the positions he took up were primarily useful in facilitating England to become more effective in possession. Mount was consistently seen participating in quick interplay and engaging in quick interplay, drawing opposition players towards certain zones, which created space for others as a third-man. Perhaps the most pertinent example of this is Mount’s combination with Sterling in the left half-space drawing attention away from Luke Shaw, who then received the ball with an extra split second to place a perfect cross for Bellingham to nod home. Incidentally, this move was also a perfect example of how Bellingham and Mount could attack in tandem to create numerical parity against Iran’s back five (Sterling had dropped off to slot Shaw in, who himself was joined by Mount, Kane, Bellingham, and Saka to create a 5v5 in the attacking line).

Mason Mount is quite a unique player in terms of how he positions himself as a #10. Rather than being a needle player, aiming to constantly receive in tight spaces between the lines, he is more pragmatic, peeling to the sides of defensive blocks to be less encumbered by congestion and defensive pressure when looking to attack. He favours progression through a quick carry forwards than a spectacular raking pass or a pinpoint through-ball; given Harry Kane seems to favour those actions, Mount complemented the attacking play nicely.

The balance offered by the midfield three of Rice, Bellingham and Mount would have been very pleasing for Gareth Southgate to witness. As a three, they cover most facets of the game, while also offering top levels of intensity, technical ability, and physical ability. It would be hard to find a more altruistic midfield in international football, whose adherence to tactical demands is so strong. This allows England to perform at a very high level on the international stage, where typically the tactical level is subpar compared to that of club football.

Kane, the front three, and chance creation

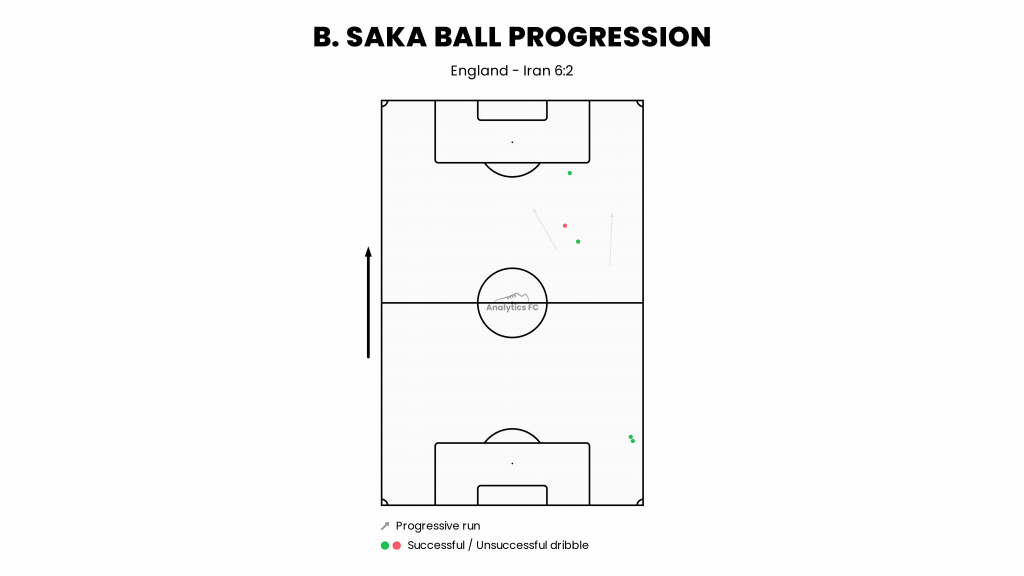

Harry Kane is an elite forward, who can hold the ball up, create chances and score vital goals to carry a team. While he would be a game-changer in any strike role, Kane is best utilised with runners around him. For Spurs, Kane typically has Son consistently making runs in-behind, but for England, starting Saka may have created some doubts surrounding whether England were going to play with runners in behind, particularly with Sterling starting off the wide-left.

Fortunately, Sterling and Saka took up ideal positions in the inside channels, with Sterling in particular firing off in-behind when Kane dropped deep. This vertical countermovement allowed England attackers to find space and create: most notably, Kane was able to turn away from pressure when on the ball in the second half, having dropped deep to receive. Sterling selflessly ran in behind to ensure Iran’s back-line was occupied when Kane vacated those spaces, while Saka was usually a menace to Iran defenders too, by holding his inverted position (even if he made fewer runs in-behind). The strength of England’s central component in build-up also meant that Shaw and Trippier could advance as auxiliary attackers on the wings, meaning England held width in attacking phases, when Saka and Sterling inverted.

England created chances frequently, despite being faced by a reasonably well organised deep block. This wasn’t merely a derivation of England’s organised and efficient build-up and progression play, but more so because of England’s effective rotations in the attacking third. Players were in constant movement, and this allowed England to distort Iran’s defensive shape, creating space to cross in the wide zone, from higher threat areas. With Trippier and Shaw primed to overlap, and Mount and Bellingham primed to make vertical runs, England never struggled to create a front five in the final third, as well as frequently creating triangles on the wings, which are so effective because a third man run could be made. Again, referring to the opening goal as an example, England were able to find Shaw in a dangerous crossing position because he made such a well-timed third-man run.

It is also worth noting England’s threat from set-pieces. In a tournament like the World Cup, the margins are fine and converting a reasonable number of set-pieces into goal-scoring chances is also very encouraging. England weren’t limited to doing this from well-executed corners finding aerial threats such as Maguire, but also managed to do this through well-coached deeper free kicks, most notably the example where Harry Kane peeled wide to whip a cross in, which almost resulted in a goal. Kane’s crossing technique is worth mentioning, because it is so unique and highly destructive. Kane doesn’t whip the ball in with air, rather he is almost lacing the ball with an angled boot to create a flat, whipped ball that will curve inwards and dip away from defenders and the keeper. It isn’t dissimilar to one of his types of through ball, where he also creates a very flat angle to the pass and such is his quality in execution he can frequently find his man despite the seemingly high-risk nature of this type of action. Trippier and Shaw, meanwhile, are England’s corner takers, with England favouring out-swingers to find Maguire at the second post. It will be interesting to see if they persist with this as Maguire is an injury doubt, and Eric Dier (Maguire’s replacement) being so effective at running across the near post, which may suit an in-swinging cross.

Summary

England were comfortable in their win versus Iran, and while a 6-2 score-line may resemble a romping win, England did only rack up 2.1xG (while they also limited Iran to barely two chances, and a dubious penalty). England were dominant, assured and sharp, and these qualities were largely a derivation of their effective tactical set-up. England made smart positional rotations, were pragmatic and altruistic in their individual approaches, and seamlessly progressed play through the thirds to create dangerous attacks. They counter-pressed relatively well, aided by a setup which favoured creating central overloads (with a midfield three and inverted wingers). For all of the talk surrounding England’s injured fullbacks, Shaw and Trippier were virtually flawless in their performance, and stuck to their tactical roles perfectly, giving England numerical overloads in the attacking third and holding the width almost single-handedly.

England will certainly face bigger threats moving forwards, but they will take a huge amount of encouragement from this performance. They may finally found a system, the 4-3-3, which fits in a majority of their star players, in a manner that is functional and accentuates the qualities of their star player Harry Kane. England had a history of prioritising stars over system, finding very little success from this, but there is a different feel about England after their opener in the 2022 World Cup.

Header image copyright IMAGO / Laci Perenyi