Jeremy Steele investigates the impact of national cultures on head coaches’ careers.

Last week, in the course of working on some analysis for one of our Coach ID clients, we delved into some data gathered by CIES Football Observatory regarding the average length of head coaches’ stay at football clubs.

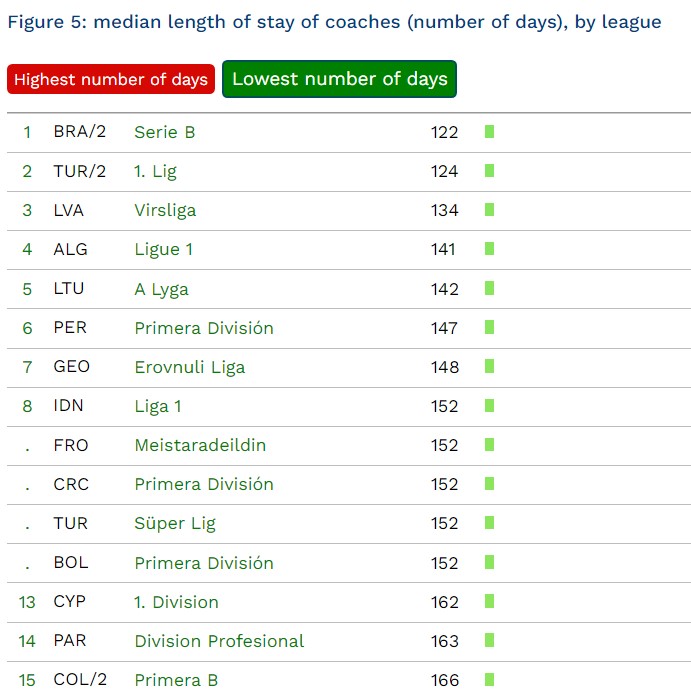

Taking information from 1,646 teams from 110 leagues in 79 countries worldwide, CIES were able to show how coach tenure breaks down from country to country. Here are two tables showing the longest median length of stay in days and the shortest median length of stay in days per country:

The differences between the length of tenure across countries are quite frankly extraordinary. It got us thinking: why are these differences so stark? What is it about certain countries or groups of countries that create a greater propensity for sacking head coaches?

After a bit of healthy discussion, one reason proposed by our analysts was “cultural differences”. This struck a chord with me. I’ve worked in Football for 16 years, including as a sporting director, coach or club advisor in 10 different countries and it’s true: every country had its own identity and ecosystem which needed to be understood to make any type of meaningful progress.

This raises an important question: in the context of data analytics, how do you explore cultural differences? How do you quantify them?

At Analytics FC, we like exploring new ideas and taking some time to delve into interesting models and data sets, so we went searching for a data set that could help us analyse this concept of “cultural differences”.

Hofstede’s “Cultural Dimensions”

One data set we discovered comes from research undertaken by Geert Hofstede and applied by Hofstede Insights, a consulting company specialising in the use of data-driven analysis to “pinpoint the role and scope of culture within an organisation’s success”. Of course, “Culture” is a pretty wide-ranging concept but Hofstede breaks it into bite-size chunks or, as he calls them, “cultural dimensions”.

Interestingly, this research has been leveraged by companies such as Nike, Mars, Sony, Unilever and Merckx. If it’s good enough for these commercial behemoths, might there not be some insight to be gained for football?

To attempt to address this question, we took a number of the cultural dimensions highlighted by Hofstede Insights in their analysis and looked to see if there was any correlation with the length of head coach’s tenure at clubs in each country.

Three dimensions jump out at us as having a strong correlation: Individualism, Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance. At first glance, these are pretty abstract concepts but bear with us and we’ll guide you through.

Individualism

The issue addressed by this cultural dimension is the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members. It has to do with whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we”.

In individualist societies, people are supposed to look after themselves and their direct family only. In collectivist societies, people belong to ‘in groups’ that take care of them in exchange for loyalty.

A nation with a high score on this dimension is a highly individualist culture. In the business world, employees are expected to be self-reliant and display initiative. Also, within the world of work, hiring and promotion decisions are based on merit or evidence of what one has done or can do.

A nation with a low score has a collectivistic culture. Belonging to an in-group and aligning yourself with that group’s opinion is important.

Groups often have strong identities. Loyalty to such groups is paramount. Relationships are deemed more important than attending to the task at hand, and when a group of people holds an opinion on an issue, they will be joined by all who feel part of that group. However, those perceived as “outsiders” can easily be excluded or considered “enemies”.

Highest-Scoring Countries: USA, Australia, UK, Hungary, Netherlands, Belgium

Lowest-Scoring Countries: Bolivia, Paraguay, Venezuela, Colombia, Indonesia, Peru

Looking at the graph above, a clear positive correlation exists between a country’s individualism rating and the median length of its coach tenure.

One interpretation of these results is that the owners or senior executives in highly-individualistic countries are much more likely to trust their employees than those in less individualistic countries.

When it comes to football, Wales top the chart in terms of head coach tenure with a median length of 943 days. You could be forgiven for thinking that this might be due to there being less at stake in a league that sits relatively low in UEFA’s Association Club Coefficient Ranking: just behind Liechtenstein in 50th place.

We took a quick look to see if UEFA Coefficient and coach tenure length showed any correlation:

As you can see from the results above, there clearly is not.

In addition, both England and Scotland feature in the top 12 countries for head coach tenure. So perhaps exploring a more UK cultural-based reason for this similarity could add some value to the discussion.

Ex-Derby County and Exeter City coach, Kevin Nicholson was Head Coach at Bangor City in Wales for 316 days. That would make him a veteran in Latvia (whose average is just 134 days) but is just 34% of the average tenure in the Cymru Premier.

“I really enjoyed my time at Bangor,” said Nicholson. “Without wishing to boast, I don’t think we ever lost two in a row during my time there so I guess I never put the board under that type of pressure to make a sacking decision based on results.

“However, my experience of Welsh football, and British football generally, is that you’re allowed to get on with your work without interference and you do get time to at least try to instil your own methods and ideas.

“I spoke with the board at the start of time at Bangor and we set some targets at the start of the season. We agreed that the team should be finishing in the top three and closing the gap on TNS.

“Other than that, I didn’t really have too much interaction with the board. I certainly didn’t feel like I had to conform to any pre-agreed methods or ‘do things like they’ve always been done’. First and foremost I was brought to the club to bring my own coaching ideas and experience. I was free to work in the way that I wanted. I felt trusted.”

Power Distance

This cultural dimension deals with the fact that all individuals in societies are not equal. “Power distance” is defined as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organisations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. It has to do with the fact that a society’s inequality is endorsed by the followers as much as by the leaders.

A high score indicates a nation where its people accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. The different distribution of power justifies the fact that power holders have more benefits than the less powerful in society. The discrepancy between more or less powerful people leads to a greater importance of status symbols.

A low score in this dimension means that being independent and considering hierarchy as for convenience only with equal rights. In a business context, there is accessible training and education, and power is decentralised with managers counting on the experience of their team members. Employees expect to be consulted, control is disliked and attitudes towards managers are on a more informal basis. Communication is direct, participative and consensus-oriented.

Highest-Scoring Countries: Slovakia, Belarus, Russia, Ukraine, Albania, North Macedonia

Lowest-Scoring Countries: Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Iceland, Sweden, Finland

The data shows a strong negative correlation between power distance and the number of days a coach stays at a club per country:

Again, the results are open to some interpretation but perhaps one way to look at the results is to say that maybe owners and executives in the highest-scoring countries expect full control and complete power over their football clubs. They wield this power in whatever way they please, be that in terms of capital investment, player recruitment or, in this case, staff hires.

Subordinates (coaches) in these environments tend to accept this behaviour as normal and have certain stronger deference to ownership. This means they accept often getting bypassed (or coerced) in some decision making processes. Staff being seen as interchangeable and being hired and fired quickly is also seen as normal.

Former Valencia B team coach, Migual Grau, recently moved from a coaching role in Cyprus to become head coach of Finnish league challengers Inter Turku. But he would appear to have reduced his risk of unemployment quite substantially by making this switch.

Assuming an appointment in pre-season and an early August regular-season start, the chances of getting fired before the third International break (in November – approximately 140 days into the season) would be 50 times more likely in Cyprus than Finland. We put these figures to Miguel to get his insight about Cyprus/Greece vs. Scandinavia.

“I am still getting to know the environment in Finland in general,“ said Miguel. “But for sure I can specify that, at FC Inter Turku, my relationship with the owners and with the sports management is one of absolute transparency. We hold weekly meetings and we cover all the aspects that surround the team, not just sports.”

“I feel the trust for me as head coach is very great,” he continued. “I feel supported and valued, and everything that is done is done to give backing to my decisions.”

“It’s very different from my time in Cyprus. There, the owners were often very strict and had to be convinced of everything. There was no absolute trust in the staff and that feeling was transferred across all departments of the club. From my perspective, there was no difference between the staff in Finland and Cyprus; the professionalism of the people in both countries is great with very well qualified people in both cases.”

Uncertainty Avoidance

“Uncertainty avoidance” has to do with the way that a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known. The definition relates to the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these.

A high score in this dimension demonstrates that as a nation people do not readily accept change and are very risk-averse. They maintain rigid codes of belief and behaviour and are intolerant of unorthodox behaviour and ideas. To minimise the level of uncertainty, there is an emotional need for strict rules, laws, policies, and regulations.

A low score in this dimension means that a nation does not need a lot of structure and predictability in its work life. Plans can change overnight; new things pop up and people are fine with it. Curiosity is natural and is encouraged from a very young age. What is different is attractive!

This also emerges throughout societies of this type in both its humour, heavy consumerism for new and innovative products and the highly-creative industries it thrives in. A low score on uncertainty avoidance is also reflected in the fact that in these societies it is ok to say “I do not know” and be comfortable in ambiguous situations in the workplace.

Highest-Scoring Countries: Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, Uruguay, Belarus, Russia

Lowest-Scoring Countries: Singapore, Denmark, Sweden, UK, Ireland, USA

Another clear negative correlation emerges between uncertainty avoidance and coach tenure:

On the face of it, this negative correlation might seem to be the opposite of what we might instinctively expect. If high-scoring countries on the “uncertainty avoidance” scale do not readily accept change, you might expect them to want to try to keep their coaches longer. At the other end of the scale, the low-scoring countries might seem more likely to stick with a manager. However, it’s important to recognise that this “uncertainty avoidance” often manifests in terms of a more authoritarian approach: an attempt to limit uncertainty through control. For example, if results start to turn, club owners and executives feel that they must do something now to avert disaster and assert their control back on the situation.

Interestingly, both Russia and Greece are high-scoring countries on the “uncertainty avoidance” scale. An interesting anecdote, which seems to highlight our research findings in one neat package, is that of the owner of Greek club PAOK, Ivan Savvidis. The man who, in 2018, stormed onto the pitch with a gun strapped to his waistband to appeal a late overturned goal in a game against AEK! Savvidis, a Russian businessman with close ties to Vladimir Putin, acquired the club in 2012 and, in that time, the club has seen 10 managers come and go. For Savvidis, uncertainty has been limited through a form of authoritarian control.

This was somewhat reflected in my experiences working in Cyprus—another high-scoring country on the “uncertainty avoidance” scale. The influence of fans and media upon club owners is extremely strong. Cypriot fans are markedly influenced by short runs of form; a ten-game win streak would have them celebrating a manager wildly, but should it be followed by three losses in a row, the mood soon changes. The fans are not shy to show their displeasure either. A “get this coach out” mindset which may take northern European club fans many months (or even years) of poor performance to adopt can ripple through a fan base in no time. This fear of disaster based on short runs of form permeates through ownership and coach changes are in turn extreme in their regularity across the league.

Conclusion

The role cultural aspects play in the way football federations and clubs are run is an important one. Generally, we tend to relate football culture and identity as something we see on the pitch, a playing style or DNA. Sometimes we refer to an identity deriving from the fans of a particular club or the character of ex-players or coaches. We seldom zoom out and assess how a country’s identity might impact upon the outcomes of leagues, clubs, coaching careers or player development.

Bringing together the Hofstede Insights study along with the CIES Football Observatory’s work on coach tenure, it’s clear that culture impacts decision making as much as any financial constraint or pressure to succeed to avoid failure. The question is: how should the football industry respond to this finding?

First and foremost, clubs (or rather those who run them) should be sensitive to the cultural tendencies within which they operate. All too often, club owners and executives can overlook the contexts they find themselves in, assuming that the way they operate is universally accepted. Having a sense of the aspects of their running processes that are culturally informed will help them recognise blind spots and could furnish them with a more open-minded outlook about possible alternative approaches in the future.

This sort of attitude is as important—if not more so—for national federations, too. In these instances where the federation represents a nation, there is an even greater likelihood for myopic thinking and a normalisation of cultural norms. Awareness of their own cultures will enable these federations to avoid falling into historical pitfalls from the outset.

Finally, the coaches themselves should take these sorts of cultural differences into account as they look to develop in their own careers. Not only should they be aware of coach tenure length in the countries that they’re considering working in, they should also keep in mind the cultural tendencies at play in the countries where they ply their trade. Sensitivity to these underlying cultural norms could be the difference between success and failure in an industry that is already fraught with uncertainty.

Header image copyright IMAGO/News Images