Jack McCormack analyses the approach taken by Roberto De Zerbi and uses our Coach ID tool to figure out a pragmatic response to his tactics

How Brighton play

Brighton are known for their desire to attract pressure, remain composed, and play through the opposition. It is no secret that their preferred method of playing comes through what I am going to call ‘enticement’, luring the opposition onto them. This being public knowledge raises the question: why don’t teams just sit deep against Brighton and look to hit them on the counter?

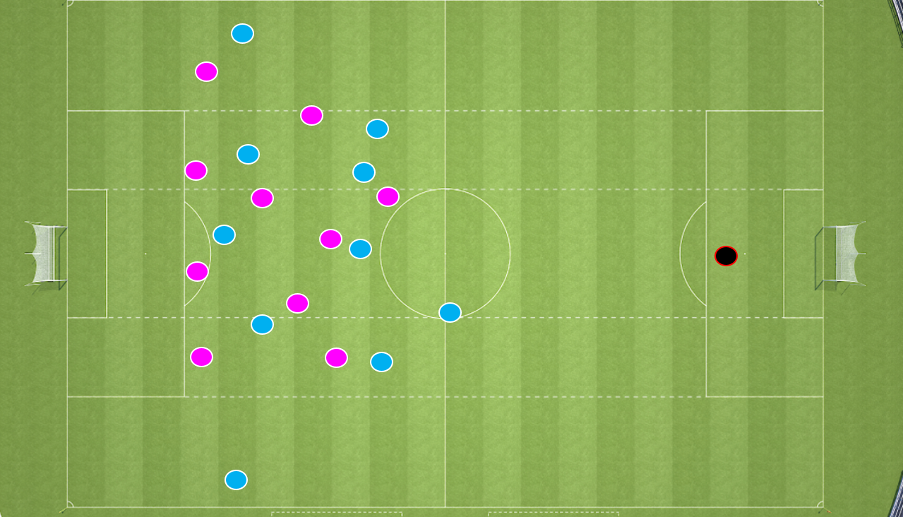

Thomas Frank on Monday Night Football suggested one should either “go fully high man to man or stay deep. Never get caught in the middle or they will play around you.” The reasoning behind this is that Brighton like to play in between the 2nd and 3rd lines, connecting play through their dropping forwards who create the classical false 9 conundrum: whether to follow and expose space in behind for the wingers to run into or, alternatively, allow the forwards to turn and face, protecting space in behind but exposing the last line.

Brighton’s playstyle, having automatic elements, which increase speed and synchronicity of thought and therefore action to an ‘unintuitive’ degree, is built around exposing slight errors in opposition timing and maximising the ‘superior knowledge’ they hold. This means that Brighton are always playing on the precipice of turnover to maximise the space created, which makes an in-between approach risky for the opposition as it creates the very complexity and doubt which Brighton prey on. Therefore, if you go man-to-man, you nullify the first progression, limiting progressive options through getting tight when play is static. This forces Brighton to use the goalkeeper as the spare player to launch more direct attacks, typically down the flanks.

Yet, this also generates risk, leaving opposition teams susceptible to the errors which can occur in duels. In addition, the direct attacks are dangerous due to Brighton’s commitment to the ‘cat-and-mouse’ game of attracting man-oriented markers deeper, often leaving defenders competing for 3v3’s in high areas. So, when going man-to-man, teams must place a lot of faith in the individual capacities of their defenders as there is a lack of systematic protection for the backline. This level of defensive variance and exposed space is understandably considered too risky for many.

Alternatively, you could prevent the creation of open conditions through not engaging in Brighton’s half. By sitting off, you refuse to engage in their enticement and create a static game state, wherein their centre backs will place their foot on the ball, slowly progress and play sideways or wall passes. This provokes a situation of stasis where both teams refuse to blink and play into the others playstyle.

The reason this seems particularly potent against Brighton is two-fold, one individual and one tactical, but with the two intrinsically interlinked: you cannot separate tactical considerations from the players you have available.

How shape affects this

Brighton play in a 2-3-5 shape when building around the half-way line as opposed to many top teams, where a 3-2-5 prevails. This exposes more space in the wide channels for Brighton, particularly due to the compactness of both centre backs in possession, which leaves the half-spaces uncovered in rest-defence (greater central compactness is often falsely synonymous with greater rest defence when in reality it is a balancing act between coverage and compactness). Compared to a 3-2-5, this leaves them more vulnerable to direct attacks following a turnover. This is for a variety of reasons.

There is more space uncovered on the last line to attack and more ground for the centre back to make-up and try to recover the ball. There are greater spaces exposed between defence and midfield during the transition period, and more rotations between midfielders and centre backs to cover the retreat defending. This means they are less frequently directly in duels with opposition strikers for headers or with their back to goal which can slow down play, bog down the centre in a contest for 2nd balls, and allow the team to regroup, preventing instantaneous progression.

Therefore, they allow teams to make significant ground vertically, which forces a whole-team retreat when the opposition successfully wins and holds the ball. This introduces more chaos from a spacing perspective as you are covering larger amounts of ground at higher intensity towards your own goal, with the opponent also having momentum towards your goal. Consequently, opposition teams can successfully gain territory against Brighton, putting them in good locations to score after recovering the ball, and in situations where Brighton’s structure is not optimally shaped, as the game is stretched and dynamic, requiring covering and tracking of runs in a more man-oriented manner.

This tactical issue is an inherent trade-off of the system and existed when, for example, Manchester City adopted a similar set-up, with fewer covering defenders leaving them more susceptible to possession errors and quick transitions hitting the backline.

However, the situation is compounded by Brighton having centre backs who struggle to cover large amounts of space effectively. The best summary is provided by the Guardiola himself:

“It is not easy to play central defender with this manager. Header, long ball, channel, channel. They have to defend 40 metres behind and make build-up, so it’s not easy, that’s why I admire a lot my central defenders.”

Given the predicament with individual defenders struggling to defend space, one is perhaps puzzled by Brighton continuing with two, rather than three, centre backs in higher building phases. But this commits the error of only looking at the downside of a trade-off and not acknowledging the strengths provided by the system, which are numerous and frequently inherent to how Brighton seek to play. The tight latticework of connections provided by the build-up shape allows Brighton to play on the precipice with less risk and look for small openings via one touch play and third man movements. A back three expands the shape and provides less potential for central infiltration via midfield connections. When the wide centre back receives, they are more isolated and can be better shifted to wide areas, contrasted with the sideways passing from the narrow two centre backs which entices players with the contingency option of a backwards pass remaining open. In essence, a 2-3 shape better facilitates extreme compactness.

Risk vs reward

The issue is moreover amplified at Brighton because of the high tempo attacks they seek to create as opposed to more Guardiolan teams. More direct disciples of Guardiola are obsessed with transition and therefore place priority on ball retention, moving forward as a team to cover gaps in rest defence, pinning the opposition back to nullify counter attacking threat, and so on. From this perspective, De Zerbi opts towards the riskier side of the trade-off when considering the vicissitudes of verticality: the quicker the ball goes forward, the quicker it comes back, and once Brighton enter the space between the 2nd and 3rd lines, they move quickly if they seek to progress. The style is then different from a ‘stability is the ball’ one, which means high possession numbers do not reflect security in the same way they do for a Manchester City. Through encouraging deep runs from full-back and central breakthroughs, Brighton leave themselves more susceptible when the turnover does occur.

I would moreover like to stress that although centre back is where this paradigm makes itself most prominently visible because of the large distances, it pervades much of Brighton’s transitional weakness. Brighton chose to prioritise highly technical midfielders, often smaller and less physically imposing, perhaps encapsulated best by Billy Gilmour. The players who tick all boxes are generally snapped up by larger teams, as has been seen with Moisés Caicedo, or Declan Rice at Aresnal. The latter also exemplifies an externality of having these complete players, which is an amplified set-piece threat, something extremely pertinent to consider when playing against lower blocks, who typically specialise in set-pieces and physicality in the box making them difficult to score against when evaluated microcosmically (corner-to-corner). Macrocosmically, however, set-pieces represent a very important threat against deeper teams because they concede more on average in dangerous areas and illustrate the aggregation of low percentage chances usually required to make a breakthrough. More complete players are generally going to pose a greater threat and increase the chance of an initial breakthrough or comeback through a set-piece, as along with their technique, they provide greater physical presence. To provide context, Brighton only scored six from set-pieces last season, ranking them 18th overall.

Expectation fundamentally must be indexed against player quality, which despite their weaknesses, Brighton are overperforming (significantly). The responsibility is on the opposition to attempt to expose Brighton’s weaker side of the trade-off, which the teams analysed, West Ham and Everton, have done expertly.

West Ham

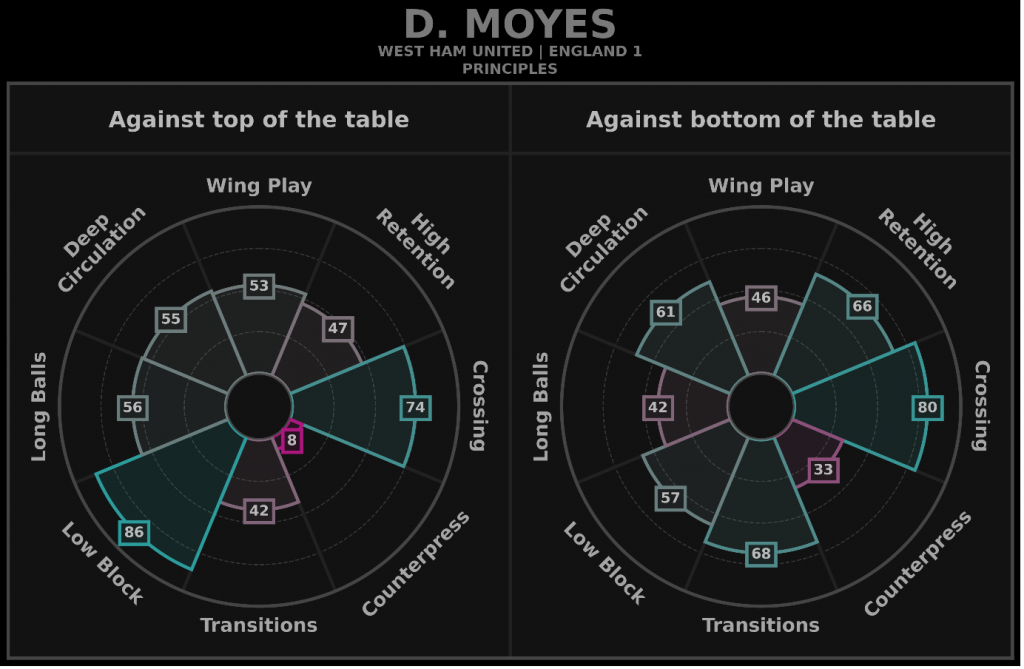

While it is generally apt to treat managers like David Moyes and the later mentioned Sean Dyche as more complex than simply being low-block managers, the graphic above demonstrates that, particularly against better sides, they are more inclined to drop deep and avoid high pressing. This article, with its case studies, will attempt to show there is more to their schemes than throwing 9 or 10 men behind the ball and launching it long, while nevertheless attempting to emphasise that often an opponent’s complexity can provide a simple route to goal.

In this game, West Ham sought to exploit James Milner and Adam Webster, constantly looking to attack Brighton’s right channel with direct balls in behind for Antonio to compete for in space. They recognised their area of superiority and Michel Antonio became their unstoppable guy (as has so often been the case). Within this execution of the predictable – Antonio being a hassle – he performed to the highest of his ceiling, which is a factor to consider when analysing pre-game; it is a contingency, but potentially something which could not be perceived as requiring an overall tactical alteration. In the pre-game analysis, you can prepare around Antonio causing trouble in the channels, that much is practically guaranteed: the extent to which that manifests on the day is unknowable (requiring as it does factors simply beyond Antonio’s own performance).

However, to avoid De Zerbian apologia, one could nevertheless argue that the average Micheal Antonio performance still exploits the massive gaps left in the channels, particularly when the full backs perform more dynamic, forward-facing actions which leaves them on the backfoot, with Webster, reliably slow, covering.

The qualitative difference between Webster and Antonio on the day made the situation untenable, and West Ham strategically prepared around that, meaning that consigning the defeat to contingency is disingenuous. But, I am willing to bet that De Zerbi knows that channel defending is a weakness of the system, but one which he considers worthwhile to enforce a particular style of play which is a net positive. Launched balls for a tenacious and physical forward to compete with in space versus an isolated centre back and retreating defence is a blueprint for exposing the weaknesses Brighton essentially seem to accept as part of their system.

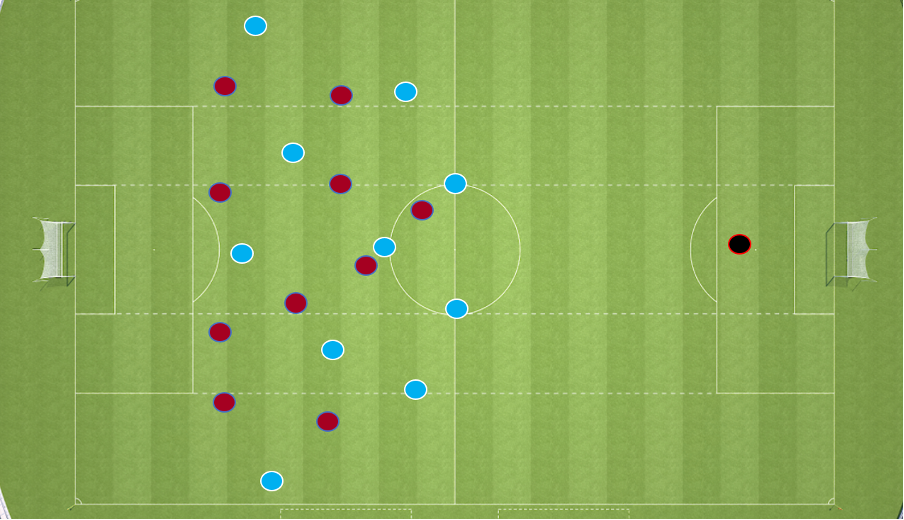

To be more particular, I think it’s important to establish the facts of what I perceived as occurring in West Ham’s defensive structure, which made it well suited against Brighton:

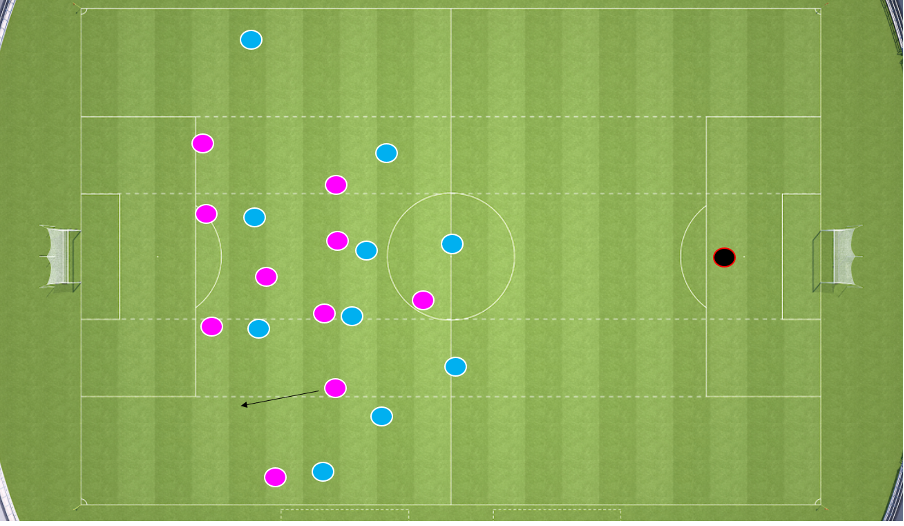

- Untroubled first build-up – very light ‘high’ press from Antonio who would do pistoning movements.

- 4-1-4-1 mid-block in basic terms. Compact centre and man-to-man engagement on the wings.

- Midfield two are man-oriented which creates asymmetry in West Ham’s defensive stucture as RCM Tomáš Soucek moves onto Gilmour, who acts as a single-pivot in build-up beyond the half-way line.

- Wingers’ role is largely zonal, occasionally jumping when an FB goes narrow to receive. Narrow shape overall.

- Wingers will not track advancing full backs around the half-way line but will tuck in to cover. They are more centrally oriented in these phases, with the full back being responsible for wide engagement, even if doubled up on.

- Alvarez plays an interesting role as the screener, picking up responsibility for the dropping forwards. This is less so for Welbeck, where he tucks into defence to cover the more man-oriented pressure of the near side CB. This is potentially due to the free right half-space dynamic and attempting to make pressure more vertical than horizontal to maintain better stucture. Can fill when needed, but generally looks to drop into the back line or onto Evan Ferguson.

- When the ball moves wide to wingers Alvarez tucks in, which provides horizontal fluidity and allows the near-side FB to step up and near-side CB to act as more of a covering player.

- Once progression has been achieved West Ham are quick to fall back, with the wingers looking to double up and the block moving backwards – happy to defend in their own third.

The interesting thing I observed from this, which is more unique to West Ham, is Alvarez’s more fluid role.

Compared with the right-sided asymmetry, another more unique facet, Alvarez’s role is easier to understand directly because it deals with a crucial threat of Brighton’s, the dropping forwards escaping their centre backs and linking up (or upsetting structure through dropping). He was the screener in between the lines, which allowed for fluid transitions between a back four and five and meant the defence did not become unstructured when attempting to get tight in between the lines. This also facilitated better situational horizontal coverage by allowing the fullbacks to engage high with a covering defender (due to him dropping), preventing Brighton’s wingers from turning and facing to progress play. This provided defensive solidity by preventing what Brighton seek to do most – link-up in between the lines through the forwards – while acting as a potential launching point for transitions. This, in essence, was a best of both world’s solution with regards to midfield and defensive coverage: West Ham were able to maintain midfield coverage to try and keep Brighton higher and be more primed for dangerous interceptions, while allowing their defenders to be more aggressive at the backs of Brighton’s forward lines through having a fluid covering player.

Overall, West Ham exploited Brighton’s desire to infiltrate centrally when an opportunity arose through their defensive positioning, while their direct wing attacks caught Webster and Milner on a bad day and their attackers played fantastically, allowing them to exploit the large spaces left by Brighton’s defensive structure (which requires defenders to be stronger in duels and better at defending space than they were). That is not a tactical cop-out, but rather a trade-off of the system, which frequently needs two defenders to cover 40 metres behind and the whole last line horizontally.

Ultimately, within the anticipated framework of a David Moyes team vs a Roberto De Zerbi team, I think the deciding factors were individual and strategic, rather than particular tactical quirks, such as the asymmetry or Alvarez’s role. Nevertheless, I do think those adaptations would provide a marginal edge which would become more pertinent when player performances were more level, and tactics viewed in the abstract.

Everton

Another team who adopted a similar blueprint to success against Brighton last season in Everton who also had respective quirks to their set-up.

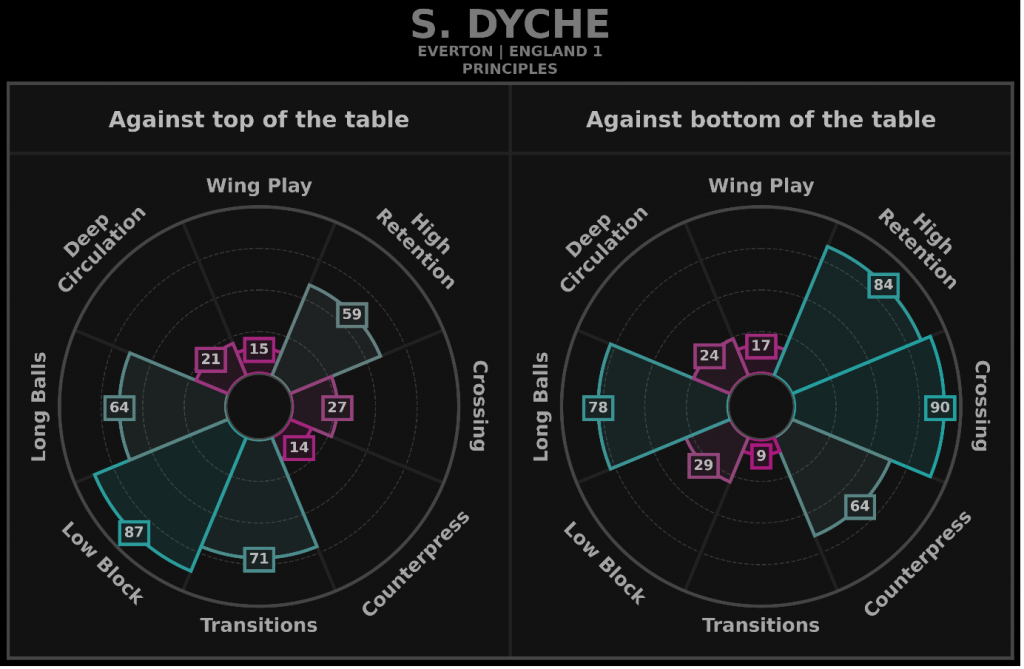

The variance in Everton’s set-up between smaller and bigger games is more pronounced than West Ham’s and I think that is reflected in the pressing approach discussed below, which places more emphasis on putting pressure on the ball carriers to force possession backwards rather than attempting to sustain higher degrees of pressing. There is a greater underlying comfortability with pushing up the pitch in a systemic manner. Nevertheless, they do sit in a low block and rely on long balls for progression against top sides.

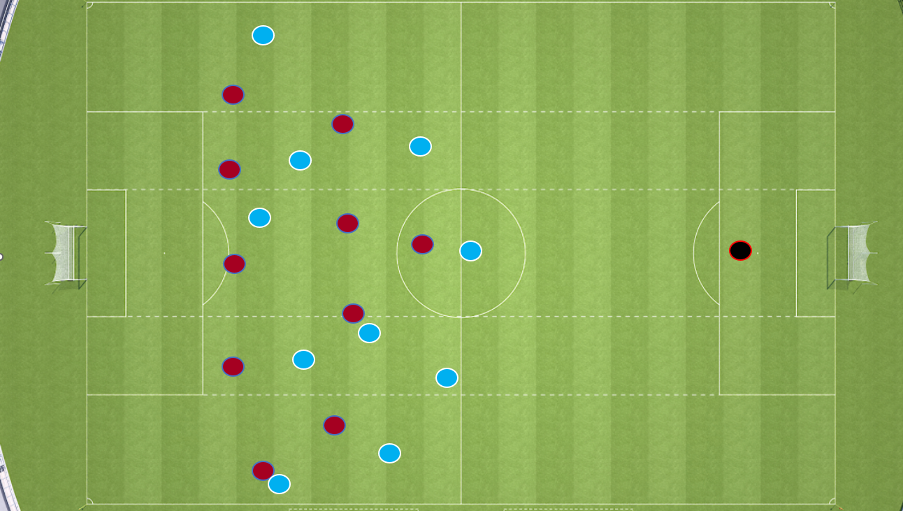

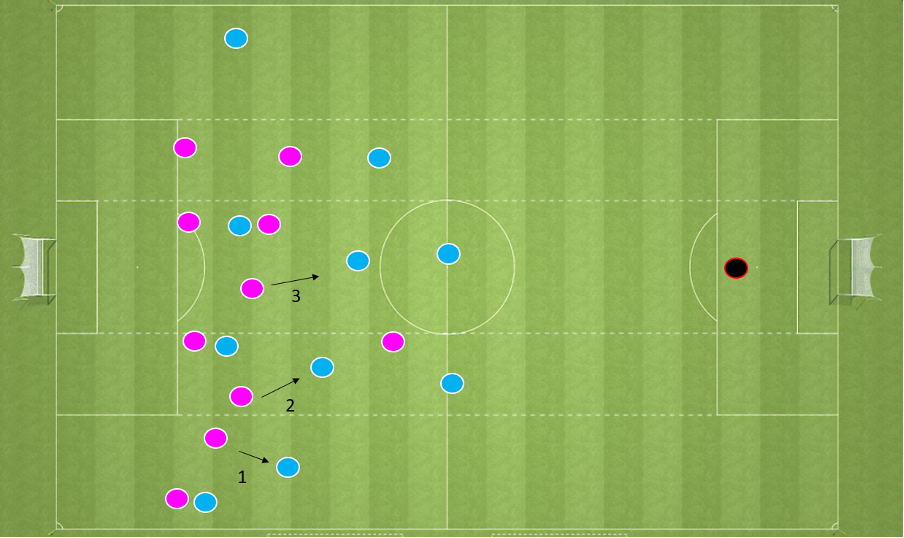

The base set-up was:

- 4-1-4-1 block allowing possession at the half-way line with the centre backs – very light press by Calvert-Lewin.

- Man-oriented midfielders which meant the shape morphed in accordance with Brighton’s midfield configuration. Subsequently, as possession progressed Doucoure would push up on holding midfielder Caicedo while Gana Gueye would step up on the dropping forward in the half-space creating more of a 4-4-1-1.

- Centre backs were allowed to progress with the ball, with Calvert-Lewin occasionally following from behind to force the defender into a more progressive (and therefore turnover-likely) position.

- Midfield typically covered around 50% of the pitch – a huge emphasis on compactness and allowing space on the far-side. The defensive line generally expanded more due to the man-orientation of the midfielders covering in gaps in addition to the winger on the near-side filling in almost instantaneously.

- Full-backs were man-oriented on the wingers and would be out quick to prevent forward reception – wingers fill-in in anticipation of runs to allow the FB to push.

- Degree of asymmetry in accordance with Brighton. Iwobi filling in on the side of Mitoma and Estupiñán was more common than McNeil on the other side, who would more often tuck in to help deal with Welbeck’s greater proclivity to drop in comparison to Undav, leaving Mykolenko more isolated against Buonanotte.

- Attempts to unsettle the block moreover reflected this, with the dropping forward, full back rotation attempting to confuse the man-oriented scheme on Everton’s right flank.

- Wingers rarely directly press FB’s – sometimes attempt to jump and even more seldom do they follow their run (only happens if CB is isolated with only GK pass remaining). Mostly about being ready to fill in, and acting as a deterrent towards FB passes to either bait a central incision or show play wide. All about having numbers back and ready to deal with rotations and attacking movement.

- Little fouls on Mitoma following his central instep were common.

- ‘Man or ball’ policy in transition when Everton had more numbers in attack. This type of attack was infrequent enough to justify a more conspicuous approach.

- When in the deeper block pressure was always applied to the ball-carrier by the nearest player to prevent them having time on the ball. Degrees of staggering in midfield typically reflected these man-oriented triggers. More vertical than a lot of deeper approaches as they looked to prevent Brighton from camping outside their box.

- Policy of hitting the flanks quickly – either through dribbling from midfielders, pre-emptive runs from wingers or more direct balls for DCL to contest.

In contrast to West Ham, there was a greater emphasis on preventing central play, compared to attempting to bait the pass. More emphasis was placed on preventing wide progression, as rather than doubling up, Everton filled in so there was cover in behind rather than ahead. This meant they were often forced deeper due to relinquishing pressure on the FB’s after winger reception.

Calvert-Lewin was more passive in his pressure than Antonio, with centre back progression being allowed with a more rigid man-to-man midfield structure being a crucial part of the game plan, as it baits the centre back out of position, and forces them to make a progressive choice. The second goal came directly from the space afforded in the right channel following Websters progression and failed pass – similar to West Ham, just in a deeper region.

The third goal also reflected the other major systemic difference which was the greater pressure placed on the ball when in a low block. Pressing the ball in a structured manner – maintaining position until ‘your man’ looks ready to receive – attempting to maintain a strong structure while not allowing any time on the ball to players who were not centre backs. From here a transition is launched, Calvert-Lewin wins his duel and Iwobi attacks the ball with momentum. A 2v1 transition is created, and although Brighton regroups well and the goal comes from bad goalkeeping, the prior principles remain.

Overall, this still fits within the basic blueprint of remain compact defensively and make the centre difficult to play through, get wingers deep on the flanks, have a physically complete striker capable of acting as an outlet, good ball carriers on the wing and a robust central midfield.

Serendipity

Perhaps the movement away from that style of football for many is why De Zerbi has thrived in particular at Brighton. Of course, he has developed as a coach over the past three or four years, this season looking to kill games with the ball more frequently rather than embrace variance when ahead, for example. But it is notable his highest finish at Sassuolo was 8th after multiple seasons in charge, compared to 6th at Brighton last season. Potentially, the more attacking and engaging approaches being favoured by new appointees in the Premier League suits De Zerbi’s football, at its best when playing through pressure (and, perhaps, there is a man-for-man superiority over his previous club). Even last season, they struggled against the likes of Spurs and Brentford – teams more likely to absorb pressure. This discomfort with counters and relatively poor rest defence goes increasingly untested as more Premier League teams attempt to proactively assert a playstyle by hiring tactically interesting coaches who represent ‘modern football’ (whatever that means) in contrast to Dyche, Conte, and Moyes. This is just a hypothesis, but one I feel relatively confident asserting, as channel defending in transition is consistently a weakness, and one which only really becomes visible when Brighton is forced to sustain possession in the opponent’s half.

Therefore, I think there is truth that De Zerbi has benefitted from serendipity as the football cycle has shifted away from more low-block oriented football at Premier League level. For many teams, there are now ideological and practical reasons behind not being able to adopt more passive forms of defending which is an exogenous factor positively impacting De Zerbi.

Conclusion

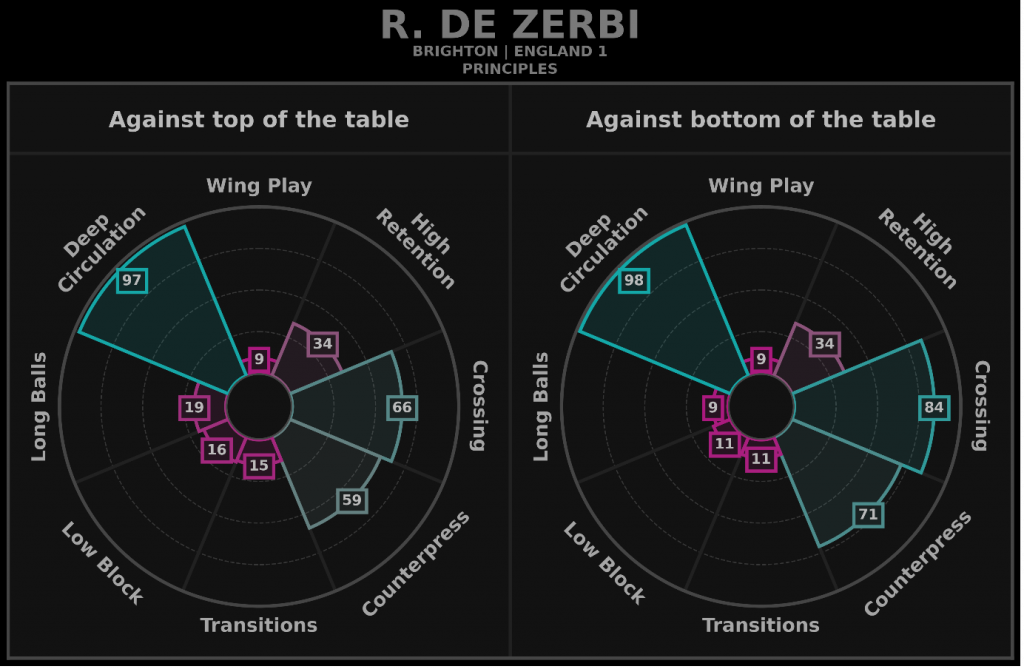

Should De Zerbi move to a super-club, which seems only inevitable, I think his style of football will have to adapt to facing deeper blocks more often, placing more emphasis on sustaining pressure, rest defence and so on. Much like how Guardiola improvised inverted full back as a response to Bundesliga counterattacks, writing De Zerbi off as only being able to succeed when facing pressure seems to underestimate the extent to which necessity is the mother of invention. His current style, with the complexity required to practice it proficiently, makes significant game-to-game deviations difficult, particularly with a packed European schedule. Teams are more likely to press, in De Zerbi’s words “a small team, a small club”, so preparing primarily around that, makes sense. Hence the lack of variation between playstyles against the top and bottom – they want to assert their style which is proactive and complex, and thus requires constant reinforcement and little deviation.

At Shakhtar, he did get caught off guard by Real Madrid’s willing to defend deeper, absorb pressure and not take the bait, and potentially, if Real Madrid can adopt such an approach without fan dissatisfaction and lack of pretence of grandeur, any Premier League team could. But I think such a perspective fails to consider the project-and-process-based nature of new Premier League appointees. However, only time will tell whether de Zerbi can or will adapt in a changing climate where teams sit deeper against Brighton. But I would argue that such adaptation is likely needed to continue succeeding to the extent he has thus far in his career.

Overall, I agree with Thomas Frank that you either go man-to-man or sit off with few exceptions. I think there have been successful examples of more hybrid pressing against Brighton – but it is more difficult, introduces more complexity, and leaves yourself more liable to humiliation should it not succeed.

Header image copyright IMAGO/Jacques Feeney/Offside Sport