Mohamed Mohamed looks at how last season’s Bundesliga surprise package play and what may now change after some big departures

Every so often, there will be a club in the Bundesliga who overachieve relative to preseason expectations. In 2023-24, Stuttgart were one of the most impressive squads in Europe, playing a proactive possession style which netted them 2nd place above perennial title favorites Bayern Munich. Of course, Bayer Leverkusen one upped them that season and did the unthinkable by ending Bayern Munich’s domestic dynasty by winning the Bundesliga title. In prior years, Union Berlin provided upset results and shook up the Bundesliga table.

Eintracht Frankfurt aren’t strangers to such a phenomenon. They barely missed out on Champions League qualification by one point in 2020-21, before winning the Europa League in 2022 and getting into the CL group stages. 2024-25 ranks as one of the club’s greatest seasons in their modern history as they finished third in the Bundesliga, a feat not accomplished since 1993. They also had a strong run in the Europa League, before losing out to Tottenham in the quarterfinals.

This was powered by their electric attack, which was one of the strongest in Europe. On a per game basis last season, among the big 5 leagues according to FBref, Frankfurt were in the top 20 for goals, shots, and non-penalty expected goals. In an era dominated by different interpretations of positional play, Frankfurt diverged with their unique playstyle. The defensive side was a lot less solid in comparison, but held up just enough to secure Champions League football once again.

Trying to replicate or even outdo a smash hit is always a major struggle in all walks of life. Frankfurt will be no exception to such a phenomenon for the upcoming 2025-26 season. Between losing key contributors, and the potential for the rest of the league to better prepare against their strengths, signs are pointing towards a step back in form. However, before attempting to project how good they’ll be, it’s important to remind ourselves of how they succeeded last season.

How Did They Play?

Even by Bundesliga standards, Frankfurt had an odd style of play going forward. It seemed like the more chaotic the state of play was, the more it was to their advantage and vice versa. This could be seen during buildup, arguably the weakest part of their system. If you’ve regularly watched Frankfurt last season, you have a rough idea of what their setup looks like during goal kick routines. It was a flat 4-2 structure with the center-backs spaced out since Frankfurt had regularly started with three CBs throughout the season. Arthur Theate would often take up positions like a customary left-back. In the latter part of last season, that shifted to a back four with Nathaniel Brown showing varied positioning, sometimes inverting into midfield or staying closer to the flank.

The data didn’t reflect kindly overall. According to MarkStats, Frankfurt conceded the 7th most dangerous possessions (unsuccessful passes, lost dribbles, or bad touches) near their own goal in the league last season. This might hint at talent issues when it came to handling pressure during this stage of play, despite how patiently they did try to build up. According to Opta Analyst, they had the 7th highest number of sequences which contained 10+ passes. A reason for this was just not having the midfielders who can escape pressure on their own when faced against man-to-man marking. As well, Kevin Trapp started the majority of last season and has not been the kind of goalkeeper to be comfortable on the ball. An example of Frankfurt’s struggles building up was their 3-3 draw vs Bayern, where they were stymied time and time again.

During settled possession in the opposition’s half, Frankfurt tended to set up in a 3-2-5 for the majority of the season but that changed on occasion to a 4-2-4 or on very rare instances, overloading the final line with a front 6. Some of this was dependent on who’s in the starting XI, but the 3-2-5 shape was consistent throughout the season under Dino Toppmöller. Frankfurt would often go long to find space in dangerous areas. This was the case when both Hugo Ekitiké and Omar Marmoush were on the squad, and after the latter’s departure in January. You’d also regularly see Ansgar Knauff active with depth runs. Sometimes Ekitiké will shift over, and Knauff would typically try and move into depth.

What was interesting with Frankfurt is for how potent their attack was, they spent less time in the final third than you’d think. MarkStats had their field tilt (measuring final third territorial dominance) in the bottom half at just under 47%. When they did have controlled possession, there was a right side bias with their play, forming 3v3s and the occasional box shape along the flank. In Knauff and right-back Rasmus Kristensen, that combo would provide those selfless runs to try and weaken defensive structures.

When Marmoush was in the squad, he and Ekitiké constantly took up different positions. There were attempts at synchronized movements where one dropped deep while the other would attempt to attack space in behind. On occasion, both will drop into pockets of space while a third teammate occupies the opposing backline. Mario Götze was important because he’d make those runs in behind from a more withdrawn position, but also showed varied movements overall. Even still, it felt like defensively organized clubs

Frankfurt’s bread and butter were attacks during unstructured scenarios. Opta Analyst had them first in direct attack sequences, originating inside the team’s own half and having at least 50% of movement towards the opposition’s goal and ending in a shot or a touch in the opposition’s box. Unsurprisingly, they were also first in shots occurring from counter attacks. They could create these opportunities from a variety of situations, including in moments when they’re defending from deep. With the off-ball runners available, along with Ekitiké as an outlet, Frankfurt just needed a sliver of an opportunity to make something happen against a non-set defense.

On the defensive side of the ball, Frankfurt were relatively passive. Public metrics which try to quantify how proactive a team is out of possession, such as the average distance of defensive line, passes per defensive actions, or high turnovers generated, had them around middle of the pack. In situations where Frankfurt would try and press the opposition, it mirrored other clubs in the Bundesliga with a major emphasis on man-to-man marking.

The front line would be passive in pressing situations, including choreographed buildup routines from goal-kicks. This wouldn’t necessarily be an issue if utilized to bait opponents into the middle for the midfielders to jump and create turnovers. However, there would be instances of indecisiveness for pressing the opposition double pivot, which had a cascading effect of allowing territory to be gained because everyone else is scrambling to different markers.

Frankfurt players didn’t seem to be strong with juggling man-marking responsibilities on the fly. The different ways of exploiting heavy man-marking presses came into play. If the opposition had the ball near the touchline, there wasn’t enough emphasis on using it as an extra defender to trap and force turnovers. Rather, they would allow inside position from not doubling up and constricting the space, being vulnerable to switches of play towards the far side against a scrambling defense. As well, it felt like the counterpress was half-hearted when Frankfurt lost possession near the opposition box. It didn’t feel like they would either fully box the opponent deep in their area or return to a super compact position.

Overall, their defensive structure could get by versus the lesser sides in the Bundesliga. However, more robust attacks like Bayern’s or Leverkusen’s could create openings by dragging man-markers out of position with coordinated sequences either during both a high press or settling into a mid-block.

How Good Were They?

After Bayern Munich and Bayer Leverkusen, there was room for upward mobility in the Bundesliga last season. Stuttgart had a downturn in form after losing several key contributors from their excellent 23-24 campaign, along with having a more packed schedule with Champions League matches through January. Both Borussia Dortmund and RB Leipzig are each dealing with their own existential crisis (although the former did sneak into the final CL spot). This allowed clubs like SC Freiburg and Mainz 05 to finish in the top 6. Frankfurt themselves were the biggest beneficiaries of such a power vacuum, vaulting into 3rd place.

The underlying numbers were solid if not unspectacular. Depending on the public model you use, they were either the 2nd or 3rd best attack in the league with a mid-table level defense by expected goals. That was enough to have a CL level non-penalty expected goal differential, although it was on the lower end of what you’d expect from a top 3 finish in the Bundesliga. According to Understat, Frankfurt’s non-penalty expected goal differential of +18.35 was the 2nd worst mark over the past five seasons, only behind the 21-22 iteration of Dortmund.

Frankfurt often got into early leads, which allowed them to take advantage of opponents overextending themselves because of game state dynamics via fast break opportunities. This helps explain why their field tilt was as low as it was, despite their success in attack. Their first half goal differential of 34-18 was only bettered by Bayern and Leverkusen.

Key Player: Hugo Ekitiké

During the first half of the season, an argument could be made for Marmoush being the engine of Frankfurt’s success in attack. Amazingly enough, despite playing less than 1500 minutes in the Bundesliga, he still finished 4th for total goals and assists. However, the totality of Ekitiké’s resume last season was hard to ignore, which is probably why Liverpool couldn’t. According to FBref, he was the league leader in cumulative non-penalty expected goals and assisted goals. Since the 2017-18 season, Ekitiké was just inside the top 10 for single season npxG+xAG/90 in the Bundesliga among players with at least 810 minutes played via Stathead. Following Marmoush’s departure in January, Ekitiké was tasked with leading the line and did so admirably.

| First Half | Second Half | |

| Shots per 90 | 3.66 | 4.29 |

| Non-Penalty Expected Goals per 90 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| Expected Assisted Goals per 90 | 0.26 | 0.22 |

| Shot-Creating Actions per 90 | 3.97 | 3.20 |

The appeal with Ekitiké is obvious; a 6’3-ish striker who is quite nimble and can do things on the ball you wouldn’t expect from a jumbo sized #9, including getting out of tight areas. He is an example of a growing trend in football today where there’s a great variety of things tall strikers can do. According to Opta Analyst, no player in the Bundesliga had more shots coming from a carry than Ekitiké’s 44, a gap of 12 over 2nd place Michael Olise. The compilation below shows how technically proficient Ekitiké can be when on his game.

Hugo Ekitike: Europe’s Most Elegant Striker

There are the obvious comparisons to Alexander Isak, another jumbo-sized striker with an elegance on the ball to their game. Both have taken interesting journeys to get to the point they’re currently at. In their younger days, Isak was considerably more shot hungry with Real Sociedad who has steadily rounded out his game in the years that followed. Meanwhile, Ekitiké’s ability to combine with others had shown through during his time in French football, but his overall development was stop and start. Moving to the Bundesliga helped massively improve his shot volume in a more attacker friendly environment at both the team and league level.

What will be interesting to monitor with Ekitiké going forward in his career is his movement off the ball. With Frankfurt’s style of play last season, along with the Bundesliga’s frenetic nature, being meticulous with off-ball runs is less of a necessity. He did show good instincts for straightline dashes towards the penalty box to be on the receiving end of shots around the 6 yard area, leading the league in this department. However, a notable % of his total shots and key passes did come from chaotic game situations. A couple of things which might help his transition in the Premier League is English football replicating the Bundesliga in terms of end to end chaos, and Liverpool continuing to create plentiful transition scenarios under Arne Slot last season.

Potential Recruitment

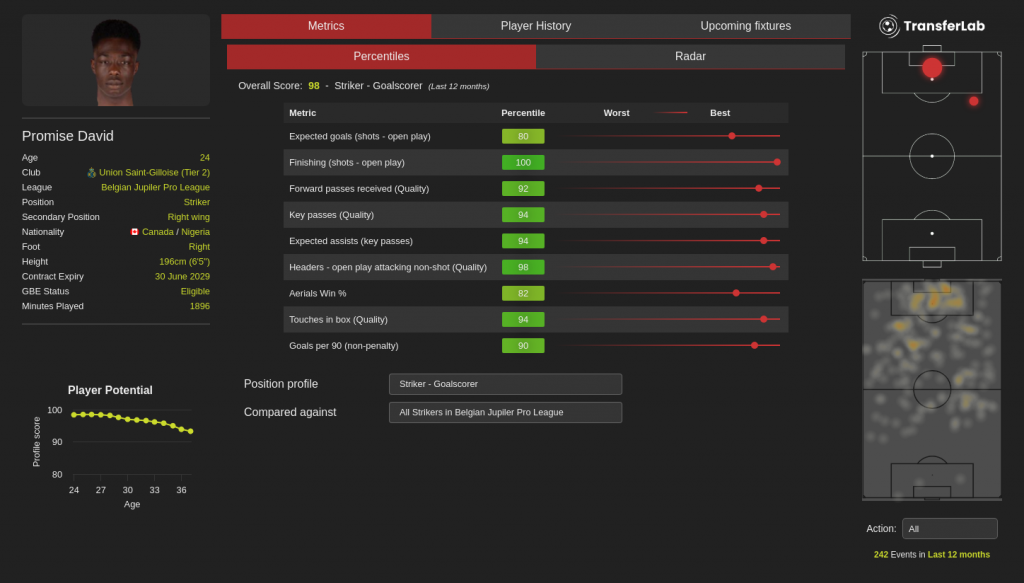

Promise David – 24 years old (Union Saint-Gilloise)

Frankfurt have had a sterling record when it comes to developing talented strikers and then selling high when interest peaks for them across Europe. It dates back to Luka Jovi? generating 22 goals and assists in nearly 2243 Bundesliga minutes during the 2018-19 season, which got Real Madrid to acquire him for an initial fee of €65 million. Arguably the most famous example was Randal Kolo Muani securing a big move to Paris Saint-Germain in the summer following 26 goals and assists in the Bundesliga in 2022-23. More recently, Marmoush and Ekitiké have made big money moves to Manchester City and Liverpool respectively.

Promise David would be on the older side, around the same age as Marmoush was when the Egyptian star signed for Frankfurt two summers ago. David has taken an unconventional route so far in his career, originally coming through the Toronto FC academy before going out to Europe and playing in Malta and Estonia. Union Saint-Gilloise signed him last summer, and his debut season in the Belgian Pro League was quite successful. FBref had him in the top 10 for total goals and assists, non-penalty goals and assists per 90, total non-penalty expected goals and assisted goals, and npxG+xAG/90, while his TransferLab profile shows elite contributions across the board relative to Jupiler Pro strikers.

David’s physicality is the big selling point of his game at the moment. Some of this can be seen with how he holds his own aerially. FBref had him in the 66th percentile for aerial wins and 89th in percentage of aerials won among forwards in the Belgian Pro League. At times during carries, it feels like opponents just bounce off of him, even if he’s not the most graceful of dribblers. Against certain defenders in Belgium, he has such an advantage to where it can sometimes look like it’s not a fair fight out there.

David’s link-up play and passing are something of a mixed bag at this stage, which makes sense given the limited experience he’s had in his career. He’s pretty good at flick-ons from headers and creating space for others during aerial duels. Making plays with his back to goal when receiving passes to feet is more of a mixed bag at the moment. If he’s able to turn and face forward in these situations, he has the awareness to try high value passes but the weighting would be off. There have been flashes of the kind of quick hitting playmaking you’d want from him.

If there is one area for David to work on, it’s become more meticulous with playing on the blindside of defenders during settled possession. At this stage, his best work tends to be curling into the channels vs higher defensive lines. This does include him initially coming back from an offside position before making that kind of run. During crossing or cut-back situations, he’s more likely to engage physically with the defender and create separation following the initial tussle. It’s worked so far against Belgian Pro League competition, and does help create space for others in a unique way, but greater diversity would help. However, given how the Bundesliga has operated tactically over the years, this would be less of a concern compared to other big 5 leagues in Europe. With Frankfurt’s history of providing a platform for strikers to perform, they’re a feasible next step for his career.

The most likely path for Promise David is as a low touch striker who makes his hey as a target man. That archetype can help create space for others, including midfielders who regularly crash the box. Such a striker can provide considerable value in the right context. A contemporary example is Dominic Calvert-Lewin, who was a high level striker for a brief stretch of time. Perhaps with more matches under his belt at a high level, David can round the rough edges of his game to become more consistent on a game-to-game basis. Clubs will find it quite tough to acquire him this summer, since he recently signed a new deal which goes until 2029 and the Belgian side already lost Franjo Ivanovi?. However, he should be on Frankfurt’s shortlist for the near future.

Conclusion

It would be fair to argue that Frankfurt were deserving of finishing 3rd in the Bundesliga last season. Their in-possession approach, while unconventional and having a hard ceiling against the stronger sides in the division, did play to the strengths of their attacking talent. Playing chaos ball while having at least one of the best forwards in the league throughout the season was the roadmap to generating strong attacking output. The defensive side leaned towards bend but don’t break territory, which was just enough to regularly win the expected goal battle against the non-elite of German football and qualify for the CL.

The question is, without either Marmoush or Ekitiké next season, how replicable can Frankfurt’s success be from playing this style of football. While the Bundesliga is panned by some for a lack of tactical diversity compared to other major leagues in Europe, it seems more likely than not opponents will catch on and force Frankfurt to beat a set defense more often. Although the remaining players on the squad should mean absolute doomsday scenarios will be avoided, it’s fair to wonder whether relying on direct attacks as much as they did last season can work once again without the absolute top-end talent.

Reports seem to indicate that despite raking in €150 million in guaranteed fees for both Marmoush and Ekitiké, Frankfurt will keep their powder dry this summer. Perhaps Jonathan Burkardt, one of only two summer signings they’ve made so far for over €20 million (with winger Ritsu Doan, who is hardly a shot monster) can shoulder the shot generation workload left behind. Burkardt had a career season with Mainz in 24-25, regularly getting into prime positions in part due to how often Mainz generated shots from high turnover (tied for 4th in the league). Having the highest conversion rate of his career thus far certainly didn’t hurt either.

The saving grace is the past handful of seasons for Frankfurt indicate that even with their tendency of buying low and quickly selling high, they can maintain an acceptable floor performance wise. From 2018-19 through 24-25, the worst league finish they produced was 11th in 21-22 (the season they won the EL). As mentioned before, there are still solid players left on the squad and they’re on the younger side of the age curve. Nnamdi Collins (21), Nathaniel Brown (22), and Arthur Theate (25) can be the backbone of a solid backline with high-end ball progression and just enough defensive solidity. At 21, Hugo Larsson is an intriguing midfielder. Along the flanks are Ansgar Knauff (21) and Jean-Mattéo Bahoya (19). It’s possible that some of these guys still have untapped potential, although not having a tentpole star forward to play off of (at least for now) might hinder their respective development.

Frankfurt were one of the surprise success stories from the 2024-25 season. Their unusual game plan in attack, combined with the star power up front, pushed them through to their best domestic season since the 1990s. The upside case for 25-26 is they can still contend for a place in Europe due to the talent still in place, with some of the prospects taking a leap in performance. The downside is those talents heavily depended on having a star to play off of, so the club might be in the wilderness without them for at least the short-term. Frankfurt have shown an impressive ability to overperform expectations time and time again. Whether they do so again or fall back to the pack will be one of the intriguing storylines of the upcoming Bundesliga season.

Header image copright IMAGO / Laci Perenyi