Jason McKenna, the Head of Content at Premier Injuries, analyses the high incidence of injuries at the start of every English Premier League season

At the start of a Premier League campaign it is expected that, on average, squads will be fully fit and ready to go. Most players will have had a full preseason in order to recover and then build for the campaign ahead. Some clubs may be unlucky with injury issues, but on the whole this is a period in the season we expect players to have the best conditioning.

It is curious then that this period of the season is one of the times we see a spike in injuries compared to the rest of the season norms. Below the data will be analysed and the reasons why this seemingly strange occurrence is happening.

The Data Used

Before beginning the analysis I will explain the methodology used and also the potential shortcomings of the conclusions.

Using Premier Injuries data I have looked at the five most recent seasons in the Premier League and calculated Injuries per 1k minutes played over the course of the season, and then comparing it to the first 4 Gameweeks. Through the article I will refer to this 1k minutes played as “exposure” as this basis for the data shows you how many injuries teams have in comparison to the time played on the pitch. Total injuries in this time frame would not give a fair reflection, whereas showing it as this “exposure” rate allows for a better understanding of trends. Lisa Hodgson Phillips explains why this is so important in evaluating sports injury incidence as “Incidence rates that do not consider exposure do not reliably indicate the problem and cannot be used to compare injury incidence” (Lisa Hodgson Phillips, “Sports injury incidence” in British Journal of Sports Medicine 2000;34:133-136).

The time period used was because this is usually the time period in which the first international break of the season happens. However, in the Season 2021/22 Premier League Gameweek 3 saw the first international break and in 2022/23 Gameweek 5 saw the international break, but for uniformity in data I set the mark at four gameweeks for each season.

Also the injuries recorded in this are described as “time loss injuries”: those in which we have seen players injured and miss out on at least one game. In all the seasons including and 2019/20 COVID-19 absence have been excluded. To simplify the data I also removed any absences due to yellow or red cards, tournaments, internal disciplinary matters, personal reasons and when they have been unable to face their parent club.

Finally, one of the problems with this analysis compared to other potential explorations of trends in recent seasons is that COVID and the Winter World Cup has meant we have not had like-for-like data to compare. This analysis goes over 5 seasons in order to give the fairest insight into this trend, but the reality is that events have made it a very anomalous data set for football injury analysis. The stats can therefore be seen to be somewhat skewed, but it still gives a useful insight into this early season trend.

The Start-of-Season Spike

During each Premier League season we observe peaks and troughs of injuries. The expectation is that the heavy fixture schedule in December and January sees the most amount of injuries. This late winter period does see a huge number of injuries with an average of 317 time loss injuries in December of each season going from 2016/17 to 2021/22.

But, as stated, this is somewhat projected as the workload of players in that period is so extreme. Squads can go from around five games in the month of November to 10 or more in the same amount of days during December and so injuries, especially soft tissue muscular ones, are more likely to happen. This is an issue we have seen grow over time as players are not required to partake in more matches than ever as the sports governing body’s ignore health professionals warnings. In an era where sports science has progressed so far we have seen a reduction in ligament injuries but not in muscle injuries due to the realities of these tight fixture schedules (see Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Kristenson K, et al “Fewer ligament injuries but no preventive effect on muscle injuries and severe injuries: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study”, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;47:732-737).

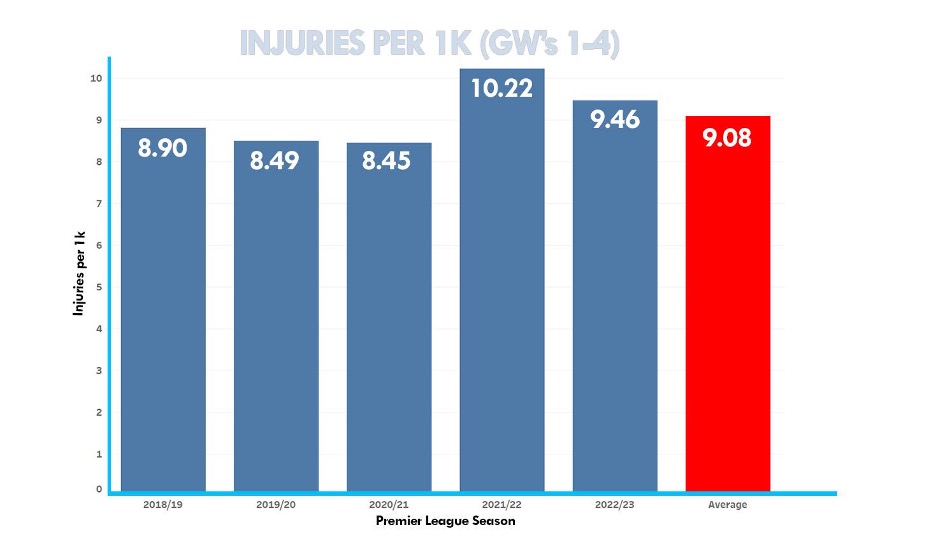

However, the start of the season should be a relatively low impact beginning to the campaign. Since 2018/19 the first four gameweeks of the Premier League season has seen teams play only 5.21 games on average. But, investigating the numbers, one can see that it is actually a time where we see more injuries than on average.

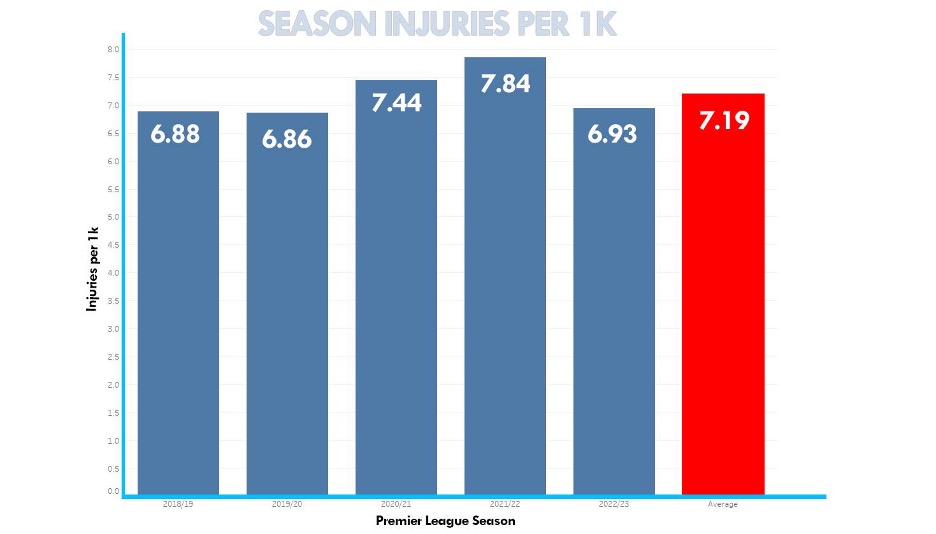

Looking at the past five seasons we can see from the graph above we can see a bit of fluctuation, but the average injury incidence rate per 1k mins of exposure is on average 7.19 injuries per squad. The highest it rose to was 7.84 injuries per 1k mins of exposure.

However, looking at the graph analysing the first gameweeks of the season we see that actually the injury incidence rate goes up as teams begin their new campaigns. This would go against usual conventional wisdom when it is believed that players are at their fittest. The 2021/22 season saw a large spike, which we shall explore below. But the data shows that the beginning of each season does see an increase in injury incidence compared to season long trends.

Why could this be happening?

The first reason why players tend to have a higher injury incidence rate is that at the start of a campaign they are acclimating to competitive top-flight football. A 2020 academic study finds that “a greater number of preseason training sessions was associated with less injury load during the competitive season in 4 out of 5 injury-related measures”(Ekstrand J et al. “Are Elite Soccer Teams’ Preseason Training Sessions Associated With Fewer In-Season Injuries? A 15-Year Analysis From the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) Elite Club Injury Study” in Am J Sports Med. 2020 Mar;48(3)).

Therefore, there is an inextricable link between a players in-season wellbeing and preseason training levels. But this preventative work only goes so far. Even if a footballer has had a full preseason and is physically fit, there is no way to replicate the rigours of a competitive football match. Match sharpness and the physicality that comes from a game that matters is impossible to replicate.

Preseason friendly games are the closest a player can get to experiencing competitive football, but the data shows that these are just not enough to push players and they only regain match sharpness after partial deconditioning over the summer through playing competitive matches once again.

This has been noted in scientific research that attests to how much mental sharpness can be lost without competitive matches. Stokes et al found that “a decline in skill execution/performance may therefore be expected from a lack of deliberate team or individual skill-based practice, and will vary with the nature and type of skill”. (Stokes KA et al. “Returning to Play after Prolonged Training Restrictions in Professional Collision Sports” in Int J Sports Med. 2020 Oct;41(13)).

This is why we see players brought back conservatively after injuries. When a player is “fit” and ready to “Return to Play” this is very different from an ability to “Return to Performance” as it will take anyone sometime to be able to get used to the real tests of a competitive match and no amount of training can prepare a footballer for that.

Another factor could be weather. The first games of the season are extremely taxing for players, but it is also often done in weather that is warmer than most of the season. The mental strain of gaining match sharpness, coupled with physical fatigue due to the climate, can test players fitness from the get go. The biggest predictor of injuries are injuries from the past. The second biggest is fatigue. During those warmer games in August at the start of the season you are more at risk of being fatigued. We have historically seen this reflected in preseason injury numbers as “overuse injuries peaked during the pre-season preparation period in July” (Ekstrand J et al. “Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study” in British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011;45).

The start of a new season can also usher in many changes at clubs. A squad may have changed manager and/ or backroom staff. The summer is a turbulent time with overhauls of high profile positions in teams and also the all important supporting individuals. Changeovers in a manager may see a new style of football adopted which may be more physically demanding or a switch in support staff may see the deployment of different methodology to training. Demands may be different on bodies which have to have time to build up tolerances to different tests.

Even without these changes the Premier League is the most physically demanding league in the world (measured by running loads and the volume of high intensity activities). Players transferring into the league typically need time to bed in and again physically adapt to the different demands they have not been used to and, of course, the majority of these players arrive to begin the new season, not midway through.

Conclusion

The data shows that at the start of each season there is an injury spike, which goes against what some would expect from incidence rates when a campaign begins. Despite players being physically fit a lack of match sharpness coupled with other factors sees a higher than average injury rate in Gameweeks 1-4 of each season compared to the rest of the season. This is despite low levels of exposure.

However the problem for clubs is that this injury spike at the start of the season is so multifaceted that it cannot be pinned down to one reason. Behind the scenes at Premier League clubs, teams are investing more money into preventative works. The technology now is so advanced heavily using tracking data, regular blood and hormonal testing, plus AI models to mitigate the risk of injuries. So if there was an easy solution to this problem then it would have been tried.

The only probable technique would be exposure management, which means that you must have the squad size to be able to rotate. It may be easier for teams with big squads who can rotate a lot at the start of the season to allow competitive minutes to be spread to players in a manageable fashion. It is a fine balancing act for teams with starting a season strong, allowing players to get competitive time on the pitch and also the long term goals of the club.

Header image copyright IMAGO /Sportimage